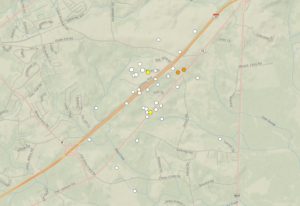

After a temporary pause in activity, two earthquakes struck central South Carolina last night, rattling residents that are already nervous from the dozens of earthquakes to hit the area since December. After nearly a week of seismic silence, a magnitude 2.3 earthquake struck near Elgin, South Carolina, at 8:42 pm. Shortly after 3am, another quake, a magnitude 2.1 event, struck nearby. With more earthquakes expected in the ongoing mystery swarm, officials are hosting a special virtual community meeting this week to keep area residents informed of the earthquakes and what local and state official scan do to help, especially if a more severe quake strikes.

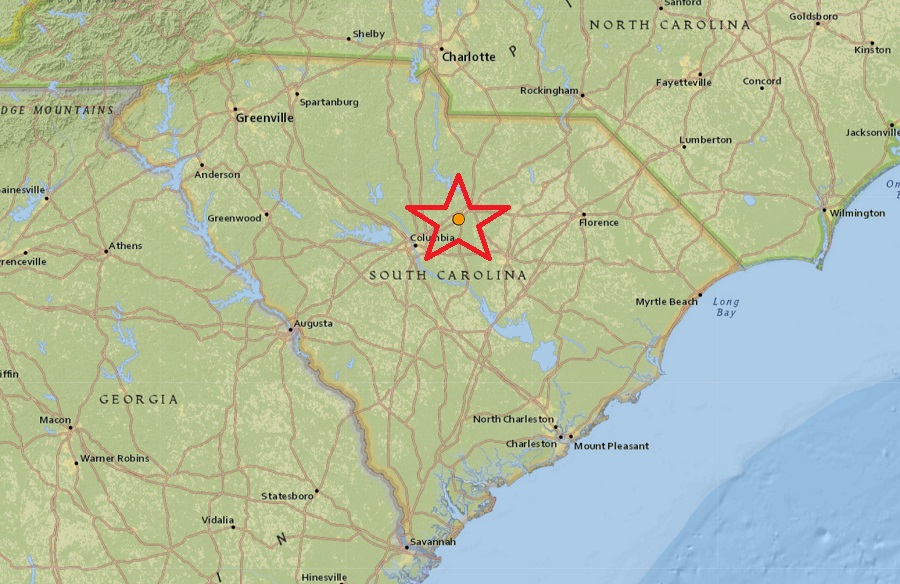

While South Carolina shakes, scientists are trying to figure out why the mysterious rattle continues. Dozens of earthquakes within this swarm have struck South Carolina over the last 7 months and these fresh overnight quakes bring the total above 70. Most of the earthquakes in South Carolina have been around Elgin, a small incorporated town in Kershaw, roughly 20 miles northeast of Columbia, the state’s capital. Elgin lies within the Carolina Sandhills region of the Atlantic Coastal Plain province; this region is characterized by many dunes of wind-blown sand that were active during the last ice age but the dunes are currently stabilized by vegetation under modern climate conditions.

The mysterious swarm began on Monday, December 27, at 2:18 pm in the afternoon. That first 3.3 magnitude earthquake hit 30 miles north of Columbia, South Carolina at a depth of only 3.1 km. More than 3,100 residents reported to USGS they felt it at the time, with one report of shaking coming from as far away as Rock Hill, which is at the North/South Carolina state border. While many felt the earthquake, there was no reported damage in the Palmetto State. That earthquake was followed by 10 more ranging in intensity between a magnitude 1.5 to a magnitude 2.6 event. The second earthquake struck three hours twenty minutes after the first one. The last earthquake in that series struck on the morning of January 5, bringing a temporary end to the earthquakes there.

According to USGS, a swarm is a sequence of mostly small earthquakes with no identifiable mainshock. “Swarms are usually short-lived, but they can continue for days, weeks, or sometimes even months,” USGS adds. However, the South Carolina event doesn’t fit the typical definition of a swarm since the first event was substantially larger than the rest.

According to USGS, “aftershocks” are a sequence of earthquakes that happen after a larger mainshock on a fault. “Aftershocks occur near the fault zone where the mainshock rupture occurred and are part of the ‘readjustment process’ after the main slip on the fault,” says USGS. However, aftershocks of a 3.3 magnitude earthquake would only last a few days, not the week plus they have.

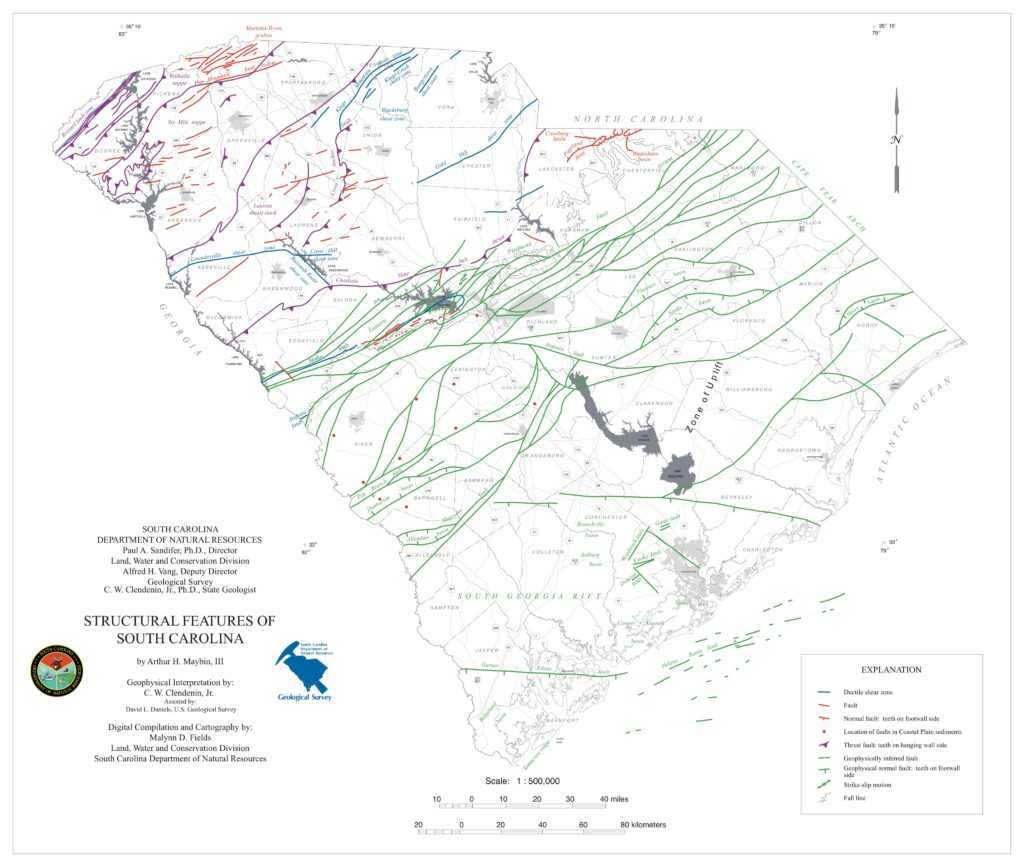

According to the South Carolina Emergency Management Division (SCEMD), there are approximately 10-15 earthquakes every year in South Carolina, with most not felt by residents; on average, only 3-5 are felt each year. Most of South Carolina’s earthquakes are located in the Middleton Place-Summerville Seismic Zone. The two most significant historical earthquakes to occur in South Carolina were the 1886 Charleston-Summerville earthquake and the 1913 Union County earthquake. The 1886 earthquake in Charleston was the most damaging earthquake to ever occur in the eastern United States; it was also the most destructive earthquake in the U.S. during the 19th century.

Experts are concerned that a large scale earthquake will strike at some point of the future and bring about significant damage and loss of life. While more than 100 years have passed since the last large earthquake, a 2001 study titled “Comprehensive Seismic Risk and Vulnerability Study for the State of South Carolina” confirmed the state is extremely vulnerable to earthquake activity. The study, based on scientific research, provided information about the likely effects of earthquakes on the current population and on modern-day structures and systems, including roadways, bridges, homes, commercial and government buildings, schools, hospitals and water and sewer facilities.

No one is sure what’ll become of this steady stream of light earthquakes or whether or not something larger is looming. For now, the SCEMD has been sending out Tweets to the people of South Carolina encouraging them to be prepared for any disaster this year –earthquakes included.

Do you know what to do if an #earthquake hits while you’re in 🛌 ? Have a 🔦 & 👞 👞 next to your 🛏 .Stay in 🛌 , don’t risk injury on potential hazards. Turn onto your stomach. Cover your head & neck with a pillow. Wait until the shaking stops. Put on 👞 before leaving 🛏 . pic.twitter.com/m5QeE12IEK

— SCEMD (@SCEMD) January 6, 2022

Earlier this month, South Carolina’s Department of Natural Resources issued a report on the Elgin-area earthquakes. Authored by C. Scott Howard, Ph. D., State Geologist, Dr. Steven Jaume, Professor within the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at the College of Charleston, Scott M. White, Ph. D., Director and Professor, with the South Carolina Seismic Network, School of Earth, Ocean, and Environment at the University of South Carolina, and Dr. Pradeep Talwani, Professor Emeritus at the School of the Earth Ocean and Environment at the University of South Carolina , the report summarized the seismic activity and offered a hypothesis being considered for their cause. One contributing factor that is being investigated is the concept of hydroseismicity, and the effect of water acting on fault planes. According to the report, the proximity of the Wateree River, fluctuating river discharges, and seasonal precipitation could be contributing to the current seismicity. The authors recommend that more studies on hydroseismicity be explored to see if it is the root cause of South Carolina’s shaking.

To keep the community informed about the swarm and to take questions from concerned residents, the Kershaw County government is hosting a Virtual Earthquake Town Hall Meeting on Wednesday, July 27, at 6pm. The event will be streamed on Facebook and YouTube; residents from Elgin can also watch the stream from the Elgin government building . Panelists include the South Carolina Emergency Management Division, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, the South Carolina Department of Transportation, and Duke Energy. Questions can be sent to panelists ahead of time by emailing earthquake@kershaw.sc.gov.