As molten lava glows within the flow field from what seems like a never-ending eruption in Kilauea’s Lower East Rift Zone, there’s more than the lava illuminating what would otherwise be a dark period in Hawaii’s history. One such bright spot is a brilliant self-proclaimed “citizen geologist”, Philip Ong. While volcano survivors refer to him lovingly as “Dr. Phil”, the social media star has many noteworthy credentials and a resume that some volcanologists would be jealous of. More than simply a citizen geologist, Ong is a serious scientist with a penchant for connecting with those in Pele’s path. With easy-to-understand terms complimented with an even-mannered tone, Ong oozes confidence and caution without panic nor hype to an audience eager for insight.

When disaster struck Hawaii Island’s Puna district, Ikaika Marzo, one of the owners of Kalapana Cultural Tours (KCT), decided to give back to the community he grew up in. Long before lava broke through the ground in Leilani Estates, Marzo and KCT ran an outfit that brought tourists out on hikes or bike rides to explore slow-moving lava flows near Hawaii Volcanoes National Park or by boat along the coast south of Kalapana. Through the KCT tours, Marzo and his team made sure to instill an aloha spirit in everything they did, injecting Hawaiian culture, story, and song wherever they could. “I never thought in my lifetime I’d see anything like this, “ Marzo told us in the days after the initial eruption in Leilani Estates. With an immediate and worsening disaster, KCT needed to stop operating and Marzo needed to focus on how to help a community ripe with problems popping up as feverishly as the volcanic fissures did in the 2018 Eruption’s early days. From the disaster rose “The Hub.”

With friends and family in Leilani Estates, Marzo was able to bring breaking news to the world through FacebookLive broadcasts. Marzo was first to share pictures of cracks that eventually became steaming cracks which in turn became the first fissures of the 2018 Eruption. Whether it was coming on to Facebook to alert people of sulfur dioxide emissions or showing video and audio of the loud jet-engine-like noise the early fissures made as they roared to life, Marzo was able to use his offline personal network and online social network to beat the traditional media with volcanic scoops. During his time at ground zero and on social media, Marzo knew there was a big void in the community.

In need of food, supplies, and information, Marzo thought the best way to help his community was to create a hub called “Pu’uhonua o Puna.” When the first Polynesians came to Hawaii, they brought a rich culture in which natural forces interacted with supernatural ones; where the forces of weather and volcanoes were married with spiritual forces and gods. It was assumed that ancient Hawaiian leadership descended from those gods. Known as the ali’i, the leadership served as instruments for the will of the gods and oversaw the communities they led. To compliment a religious-judicial system of law and order that the ali’i created, pu’uhonuas were established. Literally meaning “hill of Earth”, these pu’uhonaus were places of refuge where criminals could seek forgiveness, death penalties could be dropped, and others could find comfort and solace from the assorted dangers that lurked outside in the islands. Knowing that volcano victims were seeking comfort and solace too, Pu’uhonua o Puna was created. While the community came together to share food, water, supplies, and various services, Marzo knew that getting accurate information to the pu’uhonua visitors was key.

One such source of accurate information was Philip Ong. While Marzo continued to produce frequent FacebookLive videos of volcanic happenings in the field, Ong was designated the on-site expert at Pu’uhonua o Puna, perhaps known better as simply “The Hub”. There, he’d provide people with insight and analysis of what the volcano was doing. Using his geology background and experience working with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Ong was able to explain the physics involved of the Lower East Rift Zone, describe the mechanics of the fissures, and caution those in the immediate eruption site and beyond of what the dangers were. Interpreting and relaying reports and maps from USGS, Ong built a substantial fan-base not only at the Hub, but as a special video guest in Marzo’s FacebookLive updates. With chants of “akamai” coming from online participants in Ong’s first FacebookLive with Marzo, a local star was born.

Beyond Marzo’s fan base, Ong has crafted his own, sharing insights and reviewing photographs through FacebookLive to his own followers. When Marzo needed to leave Hawaii Island for a brief period, Ong filled in the gap, broadcasting eruption updates to Marzo’s followers. Now Ong and Marzo are regularly together in their respective broadcasts, reaching thousands of people in Hawaii and beyond with ongoing updates on the flow and its hazards. Ong’s experience with Kilauea began well before the current eruption. In 1999, Ong came to the volcano as a field assistant to a senior thesis student working with Hawaii Volcanoes Observatory (HVO.) In 1999, Ong returned as an HVO volunteer. In 2000, Ong completed a Bachelor of Science degree in both Computer Science and Geological and Earth Sciences/Geoscience from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 2004, he completed his Masters in Geological and Earth Science/Geoscience from the University of Michigan. After wrapping up a brief contracted role with the USGS and their seismology division, Ong decided to stay and make a living of being around the world’s most active and most visited volcano.

Ong found inspiration from another HVO scientist, Christina Heliker. “Christina made a career by observing conditions as they were unfolding at Mount St. Helens,” Ong said, describing that most geologists won’t necessarily have a front-row seat to a major, dynamic geoscience event unfolding before them. After completing her Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Montana and completing a Master’s thesis on inclusions in the lava dome of Mt. Saint Helens, Heliker’s career with the USGS eventually brought her to HVO in 1984, just months after the start of Kilauea’s most recent eruption which began in 1983. With Heliker around for both Mount St. Helens and Kilauea’s 1980’s eruption, Ong wanted a similar career path that brought him to the frontlines of a changing Earth. “If I pursued a typical career path in academia, I’d likely spend a lot of time in a less-active location on the mainland.” Ong said, “I preferred to stay here for a field-based experience.”

To gain the field-based experience Ong had passion for, he operated the Hawaii unit of a volcano tour company with fellow HVO volunteer Dr. Tom Pfeiffer. As General Manager of VolcanoDiscovery, Pfeiffer organizes and guides tours around the world, with a focus on Europe, East Africa, and occasionally Indonesia, Vanuatu, and Guatemala. From 2004 through 2015, Ong ran VolcanoDiscovery for Hawaii, taking tourists on special adventures around Hawaii’s volcanoes.

It was during Ong’s leadership of VolcanoDiscovery that he crossed paths with Marzo. Ong and others with VolcanoDiscovery helped educate the KCT team on the geology they were exploring with their guests so that in addition to a wealth of cultural insights, the KCT crew could provide their guests with insights and answers to the science they saw come to life around them on their tours. Ong’s company would also send their guests to KCT’s attractions and tours, such as the lava boat tours that Marzo and his crew captain.

Unfortunately for Ong, the dynamics of Kilauea eventually had a negative impact on his tour business. In 2014, a lava flow started running from a vent in Pu’u O’o cone in a northeast direction towards the Kaohe Homesteads and Pahoa. “These changes had a big impact on the industry,” Ong said. “There was great instability in the direction of the eruption. We were dealing with different flows and then suddenly theyʻre moving towards Pahoa. With lava far away from Pu’u O’o and the National Park, it wasn’t easy to tour.”

With the direction and volume of the flows as unpredictable and undependable as the tour business, Ong wrapped up operations in 2015 and decided to focus on a new endeavor. Tapping into his Computer Science background and passion for the volcanic activity on Hawaii, Ong dedicated the next portion of his professional career to developing the Eruption Lens app. Eruption Lens provides virtual tourists and live visitors to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and Kīlauea volcano with a 360° world augmented by eruption imagery. The first edition, released just weeks ago, features 12 viewpoints within the National Park, each featuring an eruption sequence of images and short video. An interactive map can be explored to check out different eruption sites and viewpoints, with links out to USGS web content for each eruption. With exclusive time-lapse video and public historical images, the app provides a completely immersive experience for all volcano visitors. While the augmented reality experience is best when used inside the national park, the app can be used anywhere. And with the national park closed due to the eruption now, this app is likely the best way to experience the historic volcanic activity inside the park from a safe distance. “This is the best way to immerse yourself into the historical record of volcanic activity (here)”, Ong said while taking us on a tour of his app at Pu’uhonua o Puna.

The app is currently available on iOS platforms for $4.99. Ong plans to release an Android version of the app, although that release schedule is dependent on how busy the current eruption keeps him. Almost a thousand people have already downloaded the app.

The transition from tour guide to app developer was a natural one for Ong. “The app allows my knowledge to become much more accessible. My tours were fairly high-end and catered to a niche audience. To create a more sustainable level of income, the app allows me to have others explore the volcano on a more mass-approach.” Beyond giving easy access, augmented or virtual, to Hawaii’s volcanoes, the app also provides users the opportunity to experience the volcano at different times in history. “The context of time is difficult to convey; this app helps bring the past to life.”

Beyond developing an Android version of Eruption Lens, which he says is “75% done”, Ong also wants to include the 2018 Eruption Event into his app development plans. “I want to create a window into our experience,” Ong describes why the 2018 event is a priority to build an app around. “We’ve never had so many fissures open up between houses and affect so many neighborhoods before. There are so many important things going on, beyond geology, that we need to share; the most important is the impact on society and people.”

And it is that impact on society and people that has driven Ong’s desire to connect with people at The Hub and on-line. In our time with Ong at The Hub, shell-shocked volcano survivors would approach Ong seeking input and advice. One unidentified woman from Nanawale Estates, another residential subdivision within the Lower East Rift Zone, asked Ong to interpret a recent USGS report that discussed risks to that area from this flow. Without missing a beat, Ong put highlights of the USGS report into layman’s terms, informing the woman of the risks and explaining the science behind those risks. While the resident showed concern for the seriousness of the situation, she appeared relieved to at least understand it.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m playing the role of counselor,” Ong said. “It’s tragic, yet fascinating how it’s all come together,” as Ong describes his experiences of interacting with the public through The Hub.

Beyond getting information they seek, the community is appreciative of getting information period. “Early in the eruption, the media wasn’t getting out information. Information was getting out from the community.” Ong said his and Marzo’s role at The Hub and with their FacebookLive broadcasts was to get accurate information out as quickly as they could. “Media wasn’t getting out information with a useful frequency,” Ong said of local and national media outlets that were covering the eruption. “Once things got started, people couldn’t even get into the scene inside Leilani Estates for any information.” Ong said his role was to “interpret data and explain the USGS data to the public. I’ve come into that role by being a non-government scientist.” And because of the efforts from The Hub, Ong feels that “the community is much more informed and educated.”

While Ong is dealing with this eruption and the problems it creates, Ong is concerned about what will happen next. Short-term, residents may become complacent with the risks of the ongoing hazard. Long-term, residents in other high-risk areas around Hawaii may not be properly prepared when the next volcanic disaster strikes.

“I fear some people are complacent here, “ Ong said. “It’s natural that people are looking for stability. Humans can’t live on the edge indefinitely.” Ong is concerned about people living around the eruption site today. “There are people living in Leilani that shouldn’t, but some may be doing it out of necessity. Can’t judge whether or not that’s complacency , acceptance of the risks, or denial. Denial is a phase of the response, and I see it as a phase that repeats itself, with occasional slips into depression and anger.”

Denial or not, other areas of Hawaii are just as vulnerable to lava flows as the area being covered by today’s flows. Ong said Nanawale Estates and Ocean View are examples of other communities at high risk that may not be doing enough to prepare when a Leilani-like disaster envelops them in lava and toxic volcanic gas.

“I think those subdivisions should never have been built there in the first place, but now we need good plans for their eventual impact,” Ong says.

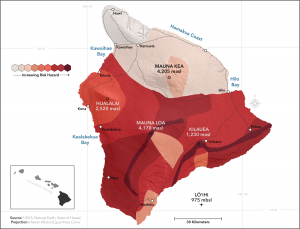

The first USGS map showing volcanic hazard zones on the Island of Hawaii was prepared in 1974 and revised in 1987 and 1992, well after construction on Leilani Estates, Nanawale Estates, and Ocean View began. The latest map divides the island into nine zones, with lava flows most likely to occur in Zone 1 and least likely in Zone 9. According to HVO, the zones are based on the mapped locations of vents and lava flows, frequencies of past eruptions, written eruption accounts, and oral traditions of Hawaiians such as chants and stories about eruptions. HVO cautions that the hazard boundaries are approximate and that the change in the degree of hazard is generally gradual rather than abrupt.

The probability of future lava flows is not the same for all areas of the Island of Hawai‘i. The long-term lava-flow threat is greatest on Kīlauea and Mauna Loa, the two most active volcanoes, followed by Hualālai.

Even larger populations around Kona or Hilo may not be prepared for a more significant eruption from the island’s largest active volcano. “This will happen again. When Mauna Loa erupts, are we ready?”, asks Ong. “Hopefully our experiences with this eruption will help us get through the next one better.”

Beyond chatting with people at The Hub or interacting with followers on FacebookLive, Ong also is part of the Hawaii Tracker team. Hawaii Tracker is another Facebook page that boasts over 42,000 members. The public group shares important information about the volcanic activity, with content curated from a few key members, of which Ong is one. To help cover the time and expense of what the key content curators with Hawaii Tracker do, they recently launched an online fundraiser seeking donations from those that wish to contribute.

Ong also hopes that sales of his app pick-up. “I haven’t received any income since the eruption,” Ong tells us. The countless hours he’s spent at The Hub or on FacebookLive came without any pay. Since The Hub opened, Ong says he thinks he’s interacted with more than 1,000 visitors there. His FacebookLive broadcasts generate 5-10 thousand views each, according to Facebook. Beyond generating income from app sales, Ong believes the future evolution of The Hub or Hawaii Trackers may also provide a way to help monetize his efforts. “Rather than do a FacebookLive at the Hub, I may be able to do a special appearance at a local venue that could host a chat.” Such an arrangement could be mutually beneficial, providing a revenue stream to Ong while providing a boost in business to venues that may be suffering in the volcano-impacted economy.

What else does Ong want? “I want the eruption to end.” He added, “I think it’s impossible for the current eruption rate to continue. After all, the summit can’t collapse forever.” Not knowing when it’ll end is tough on the community and tough on Ong. “I can’t really commit to anything, because I’m not sure how things will happen.” But one thing is certain: the bright spot in this dark chapter of Kilauea will continue to shine bright. No matter what happens, Ong says he’ll “keep doing it. Keep giving updates. Keep advising people.” As long as Kilauea keeps up, Ong will be there with it to give the community information and peace of mind.