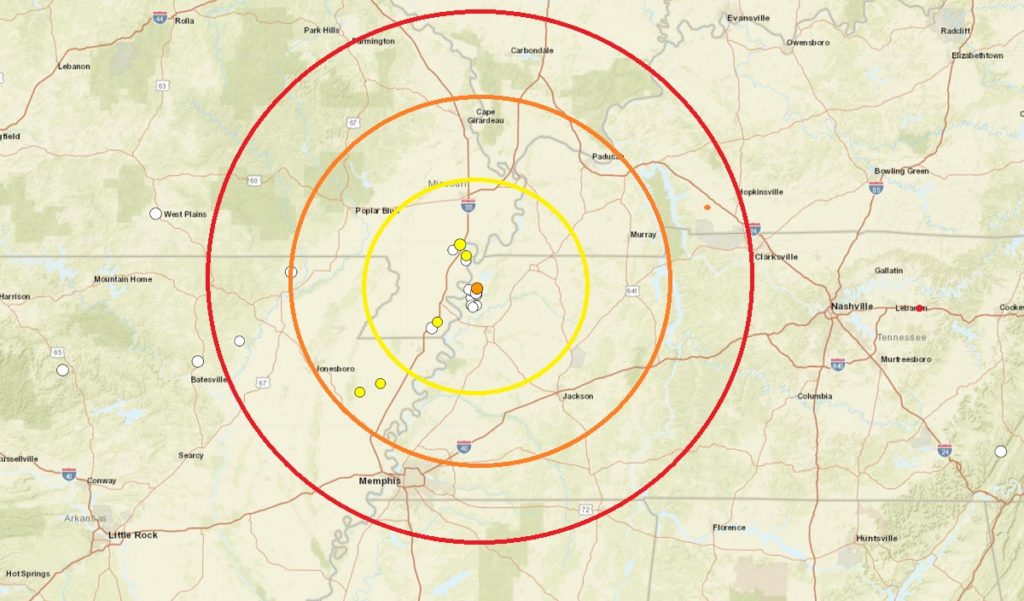

A mild earthquake struck western Tennessee this morning right in the heart of an area known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ); according to USGS, several residents used their “Did you feel it?” tool on their earthquake reporting website to report shaking they experienced today. The magnitude 2.7 earthquake, the strongest of 20 earthquakes to strike the area in the last 30 days, had an epicenter located between Ridgely and Wynnburg in Western Tennessee, not far from the Mississippi River and not far from New Madrid, Missouri, home to one of the strongest earthquake events to strike the United States. The earthquake struck at 8:10 am local time.

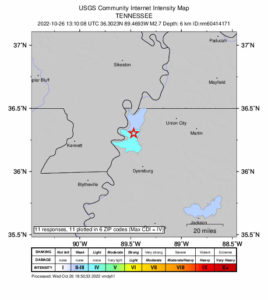

Today’s earthquake struck at a depth of 6.1 km or roughly 3.8 miles. Based on reports submitted by people in the area hit by the earthquake, USGS rated the quake a IV class seismic event on a Roman Numeral scale of 1-10 or I to X, where I is a seismic event that no one feels whereas X is one where there is catastrophic destruction. Today’s “light” shaking event was felt across portions of northwestern Tennessee, with more shaking reported south of the earthquake’s epicenter than north of it.

While today’s earthquake and other ones like it in recent days haven’t been impressively strong, they have been impressively voluminous. Earthquake volume in the NMSZ is running about 300% above normal since the summer.

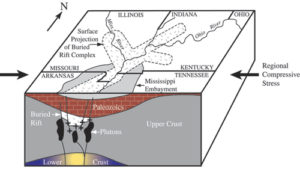

The New Madrid Seismic Zone, known as NMSZ for short, extends 120 miles south from Charleston, Missouri, following Interstate 55 to near Marked Tree, Arkansas. The NMSZ consists of a series of large, ancient faults that are buried beneath thick, soft sediments. These faults cross five state lines, the Mississippi River in three places, and the Ohio River in two places.

According to the Missouri Department of Public Safety, the New Madrid Seismic Zone is active and averages about 200 measured events per year (magnitude 1.0 or greater). Tremors large enough to be felt (magnitude 2.5 – 3.0) occur annually. On average every 18 months, the fault releases a shock of magnitude 4.0 or greater, which is capable of local minor damage. A magnitude 5.0 or greater occurs about once per decade, can cause significant damage and be felt in several states.

The NMSZ is best known for a seismic event that unfolded in 1811 and 1812. On December 16, 1811, at roughly 2:15am, a powerful 8.1 quake rocked northeast Arkansas. The earthquake was felt over much of the eastern United States, shaking people out of bed in places like New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, SC. The ground shook for an unbelievably long 1-3 minutes in areas hit hard by the quake, such as Nashville, TN and Louisville, KY. Ground movements were so violent near the epicenter that liquefaction of the ground was observed, with dirt and water thrown into the air by tens of feet. President James Madison and his wife Dolly felt the quake in the White House while church bells rang in Boston due to the shaking there.

From December 16, 1811 through to March of 1812, there were over 2,000 earthquakes reported in the central Midwest with 6,000-10,000 earthquakes located in the “Bootheel” of Missouri where the New Madid Seismic Zone is centered.

The second principal shock, a magnitude 7.8, occurred in Missouri weeks later on January 23, 1812, and the third, a 8.8, struck on February 7, 1812, along the Reelfoot fault in Missouri and Tennessee.

The main earthquakes and the intense aftershocks created significant damage and some loss of life, although lack of scientific tools and news gathering of that era weren’t able to capture the full magnitude of what had actually happened. Beyond shaking, the quakes also were responsible for triggering unusual natural phenomena in the area: earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake smog.

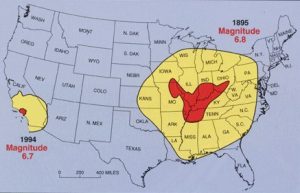

Due to the geological construct of soil and rocks in the region, earthquakes in this part of the country can be far more impactful than quakes in the U.S. West. The magnitude 6.8 event in the NMSZ in 1895 was felt over a far greater area than the 1994 Los Angeles earthquake.

Due to the population explosion that has occured in this part of the United States since the late 1800’s, there’s concern that a significant earthquake in the NMSZ today would lead to a massive damage and death toll.

To prepare for the next earthquake in the NMSZ or elsewhere, scientists and first responders hosted the “Shake Out” global earthquake drill last week on October 20, at 10:20 am local time. The purpose of the ShakeOut is to practice how to protect ourselves and for everyone to become better prepared. The goal of the drill is to prevent a major earthquake from becoming a catastrophe. Thousands of state and local organizations are participating in the drill ranging from state governments to local schools and hospitals. An estimated 19.4 million people said they planned to participate in this year’s drill, with 17 million from the United States alone.

Beyond preparing for shaking, the USGS also cautions people to be prepared for liquefaction. During the 1811-1812 earthquakes, an eruption of water and sand came to the surface in a phenomena known as “sand blows.” This phenomenon called earthquake-induced liquefaction is the process by which water-saturated, sandy sediment temporarily loses its strength due to the buildup of water pressure in the pores between sand grains as seismic waves pass through the sediment. If the pore-water pressure increases to the point that it equals the weight of the overlying soil, the sediment liquefies and behaves as a fluid. The resulting slurry of water and sediment tends to flow towards the ground surface along cracks and other weaknesses. Overlying soil “floating” on liquefied sediments moves down even gentle slopes, causing fissuring and lateral and vertical displacements. This type of phenomena can damage all kinds of infrastructure from bridges to buildings during significant earthquakes. Beyond preparing for shaking, people in this region should also be on alert for liquification from future significant earthquakes.