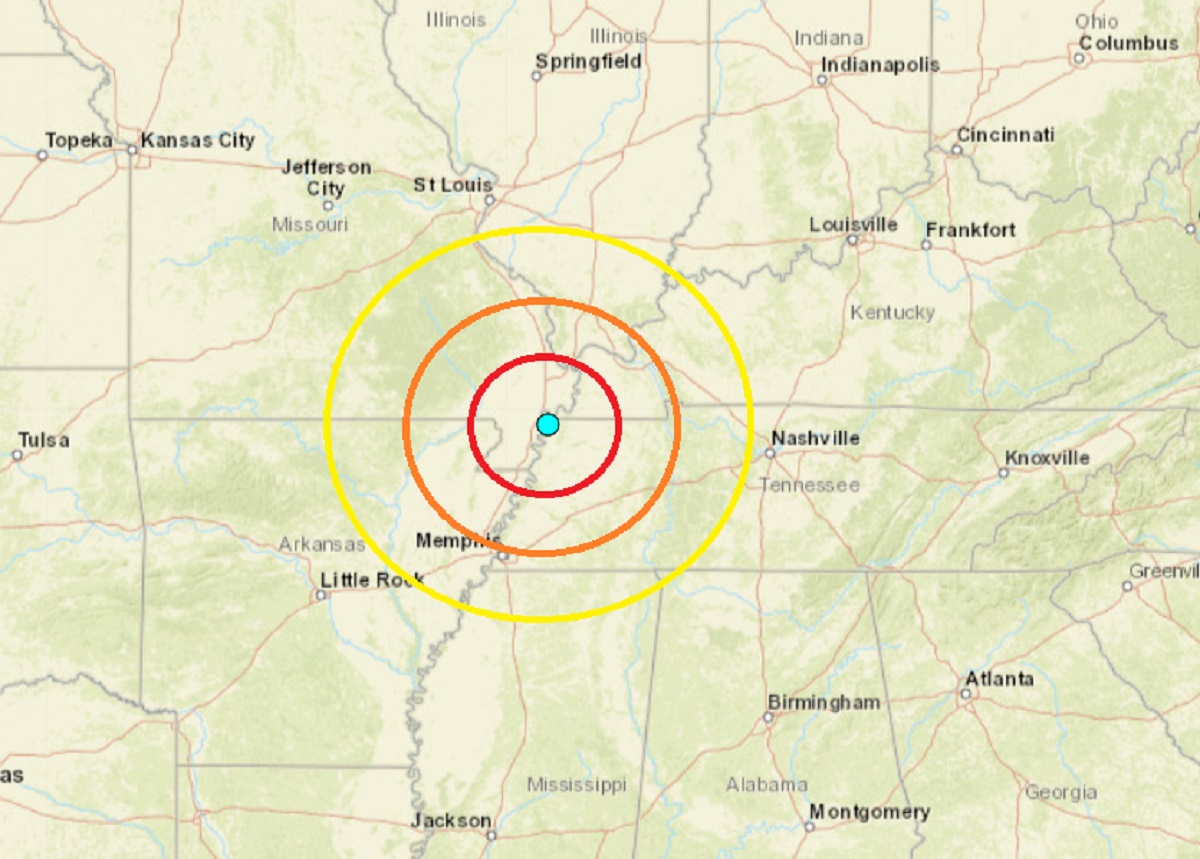

Yet another quake struck today around the New Madrid Seismic Zone, this time right in the heart of it in western Tennessee. The magnitude 2.3 event was weak, but people as far away as Missouri and Kentucky reported to the USGS that they felt the earthquake. The earthquake, which struck at 4:02 am this morning, had an epicenter near the town of Tiptonville, Tennessee, next to the border with Kentucky and Missouri –and also close to New Madrid County, Missouri, home of epic earthquake activity in the 1800s. Today’s earthquake is the 56th to strike the region in the last 30 days and the 11th to hit the heart of the New Madrid Seismic Zone in the last 7 days.

Today’s earthquake in Tennessee is not related to the overnight earthquake in Maine; the locations are very far apart and share no seismic similarity.

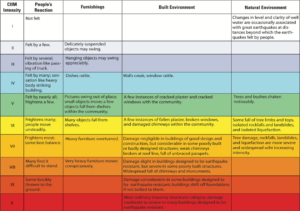

While there were no reports of damage from the relatively weak earthquake. Generally earthquakes of magnitudes 3.0 or greater are widely felt; however, in earthquakes in the central and eastern states, earthquakes weaker than 3.0 can be heard or felt due to how rare they are and how well even weak earthquakes are transmitted through the rock found in this part of the country. In general, USGS rated this earthquake as a level III event on a scale that uses Roman Numerals of I for the weakest earthquakes and X for the strongest.

While today’s earthquake and other ones like it in recent days haven’t been impressively strong, they have been impressively voluminous.

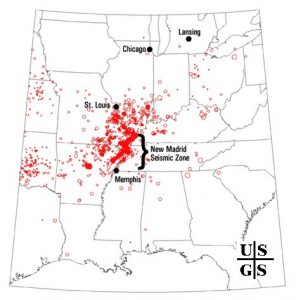

The New Madrid Seismic Zone, known as NMSZ for short, extends 120 miles south from Charleston, Missouri, following Interstate 55 to near Marked Tree, Arkansas. The NMSZ consists of a series of large, ancient faults that are buried beneath thick, soft sediments. These faults cross five state lines, the Mississippi River in three places, and the Ohio River in two places.

According to the Missouri Department of Public Safety, the New Madrid Seismic Zone is active and averages about 200 measured events per year (magnitude 1.0 or greater). Tremors large enough to be felt (magnitude 2.5 – 3.0) occur annually. On average every 18 months, the fault releases a shock of magnitude 4.0 or greater, which is capable of local minor damage. A magnitude 5.0 or greater occurs about once per decade, can cause significant damage and be felt in several states.

Earthquake volume in the NMSZ is running about 300% above normal this summer. On Wednesday, a pair of quakes rocked Arkansas and Missouri. Days earlier, earthquakes hit Georgia and Tennessee…just after an earthquake hit outside of Atlanta, Georgia days before.

While recent earthquakes in the NMSZ haven’t been very strong nor created any damage, the same wasn’t true for a series of earthquakes that struck during the winter of 1811-1812.

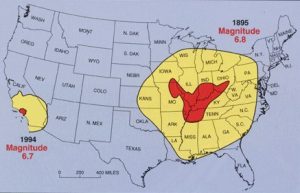

While the US West Coast is well known for its seismic faults and potent quakes, many aren’t aware that one of the largest quakes to strike the country actually occurred near the Mississippi River. On December 16, 1811, at roughly 2:15am, a powerful 8.1 quake rocked northeast Arkansas in what is now known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The earthquake was felt over much of the eastern United States, shaking people out of bed in places like New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, SC. The ground shook for an unbelievably long 1-3 minutes in areas hit hard by the quake, such as Nashville, TN and Louisville, KY. Ground movements were so violent near the epicenter that liquefaction of the ground was observed, with dirt and water thrown into the air by tens of feet. President James Madison and his wife Dolly felt the quake in the White House while church bells rang in Boston due to the shaking there.

But the quakes didn’t end there. From December 16, 1811 through to March of 1812, there were over 2,000 earthquakes reported in the central Midwest with 6,000-10,000 earthquakes located in the “Bootheel” of Missouri where the New Madid Seismic Zone is centered.

The second principal shock, a magnitude 7.8, occurred in Missouri weeks later on January 23, 1812, and the third, a 8.8, struck on February 7, 1812, along the Reelfoot fault in Missouri and Tennessee.

The main earthquakes and the intense aftershocks created significant damage and some loss of life, although lack of scientific tools and news gathering of that era weren’t able to capture the full magnitude of what had actually happened. Beyond shaking, the quakes also were responsible for triggering unusual natural phenomena in the area: earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake smog.

Residents in the Mississippi Valley reported they saw lights flashing from the ground. Scientists believe this phenomena was “seismoluminescence”; this light is generated when quartz crystals in the ground are squeezed. The “earthquake lights” were triggered during the primary quakes and strong aftershocks.

Water thrown up into the air from the ground, or the nearby Mississippi River, was also unusually warm. Scientists speculate that intense shaking and the resulting friction led to the water to heat, similar to the way a microwave oven stimulates molecules to shake and generate heat. Other scientists believe as the quartz crystals were squeezed, the light they emit also helped warm the water.

During the strong quakes, the skies turned so dark that residents claimed lit lamps didn’t help illuminate the area; they also said the air smelled bad and was hard to breathe. Scientists speculate this “earthquake smog” was caused by dust particles rising up from the surface, combining with the eruption of warm water molecules into the cold winter air. The result was a steamy, dusty cloud that cloaked the areas dealing with the quake.

The February earthquake was so intense that boaters on the Mississippi River reported that the flow of the water there reversed for several hours.

The area remains seismically active and scientists believe another strong quake will impact the region again at some point in the future. Unfortunately, the science isn’t mature enough to tell whether that threat will arrive next week or in 50 years. Either way, with the population of New Madrid Seismic Zone huge compared to the sparsely populated area of the early 1800s, and tens of millions more living in an area that would experience significant ground shaking, there could be a very significant loss of life and property when another major quake strikes here again in the future.