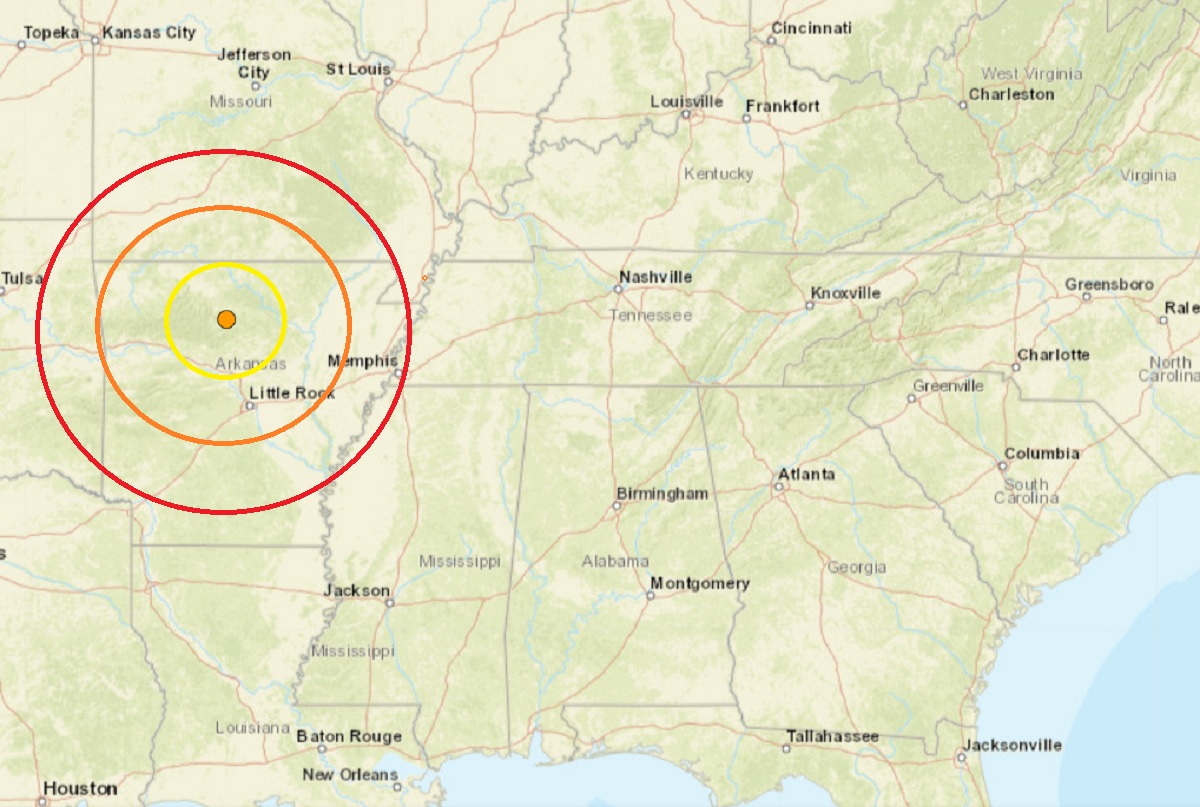

Sunday morning kicked-off with a light earthquake in northern Arkansas. The magnitude 2.1 earthquake struck north-central Arkansas this morning half way between Little Rock and the state line with Missouri, according to USGS. Weak shaking was reported near Mountain View from today’s seismic event. The earthquake hit at 2:06 am local time; the epicenter, which was located just west-southwest of Leslie, had a depth of 3.5 km.

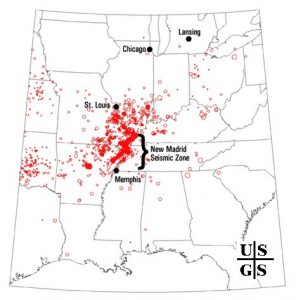

Today’s earthquake didn’t strike far from the heart of the New Madrid Seismic Zone, or NMSZ for short. Over the last 30 days, there have been 25 earthquakes in the NMSZ area and today’s earthquake in Arkansas was the strongest of the bunch. The NMSZ has a history of destructive earthquakes.

While today’s earthquake was relatively inconsequential, authorities are concerned that people aren’t properly prepared for when a big earthquake will strike this region. The matter of a larger destructive earthquake in this area is more of a matter of “when” rather than “if.”

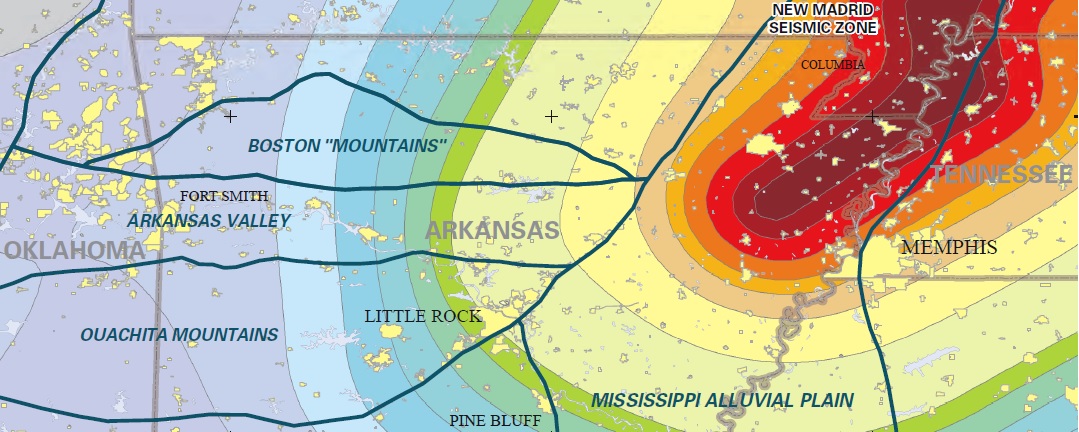

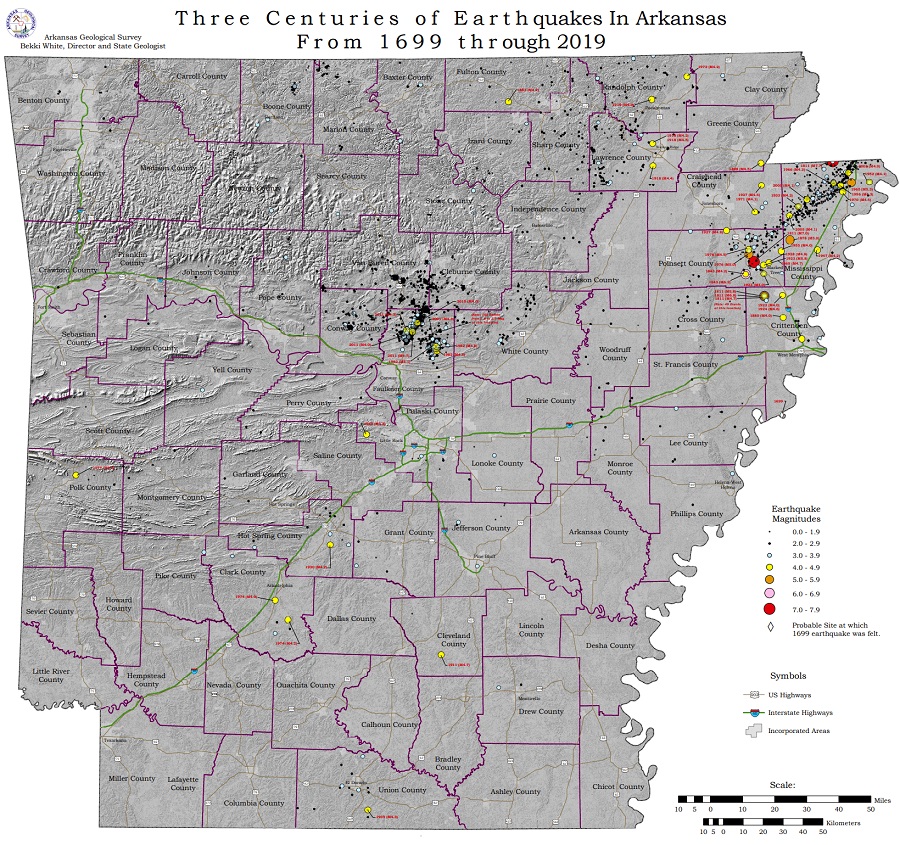

Arkansas isn’t a stranger to earthquakes. According to the Arkansas Geological Survey, hundreds of earthquakes have been reported throughout the state over the last several hundred years, with records going as far back as 1699. While many are centered near the heart of the NMSZ closer to the Tennessee/Missouri border, there are also pockets of seismic activity near today’s earthquake across Sharp, Lawrence, and Randolph Counties as well as across the middle of the state north of Little Rock.

While earthquakes of varying intensity have struck the state over the last several decades, the most noteworthy seismic event occurred during the winter of 1811-1812 when the NMSZ unleashed a swarm of destructive earthquakes. Unfortunately, many seismologists believe that the future will feature earthquakes just as strong as the ones that unfolded on December 16, 1811.

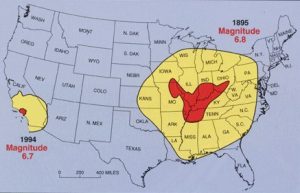

While the US West Coast is well known for its seismic faults and potent quakes, many aren’t aware that one of the largest quakes to strike the country actually occurred near the Mississippi River. On December 16, 1811, at roughly 2:15am, a powerful 8.1 quake rocked northeast Arkansas in what is now known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The earthquake was felt over much of the eastern United States, shaking people out of bed in places like New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, SC. The ground shook for an unbelievably long 1-3 minutes in areas hit hard by the quake, such as Nashville, TN and Louisville, KY. Ground movements were so violent near the epicenter that liquefaction of the ground was observed, with dirt and water thrown into the air by tens of feet. President James Madison and his wife Dolly felt the quake in the White House while church bells rang in Boston due to the shaking there.

But the quakes didn’t end there. From December 16, 1811 through to March of 1812, there were over 2,000 earthquakes reported in the central Midwest with 6,000-10,000 earthquakes located in the “Bootheel” of Missouri where the New Madid Seismic Zone is centered.

The second principal shock, a magnitude 7.8, occurred in Missouri weeks later on January 23, 1812, and the third, a 8.8, struck on February 7, 1812, along the Reelfoot fault in Missouri and Tennessee.

The main earthquakes and the intense aftershocks created significant damage and some loss of life, although lack of scientific tools and news gathering of that era weren’t able to capture the full magnitude of what had actually happened. Beyond shaking, the quakes also were responsible for triggering unusual natural phenomena in the area: earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake smog.

Residents in the Mississippi Valley reported they saw lights flashing from the ground. Scientists believe this phenomena was “seismoluminescence”; this light is generated when quartz crystals in the ground are squeezed. The “earthquake lights” were triggered during the primary quakes and strong aftershocks.

Water thrown up into the air from the ground, or the nearby Mississippi River, was also unusually warm. Scientists speculate that intense shaking and the resulting friction led to the water to heat, similar to the way a microwave oven stimulates molecules to shake and generate heat. Other scientists believe as the quartz crystals were squeezed, the light they emit also helped warm the water.

During the strong quakes, the skies turned so dark that residents claimed lit lamps didn’t help illuminate the area; they also said the air smelled bad and was hard to breathe. Scientists speculate this “earthquake smog” was caused by dust particles rising up from the surface, combining with the eruption of warm water molecules into the cold winter air. The result was a steamy, dusty cloud that cloaked the areas dealing with the quake.

The February earthquake was so intense that boaters on the Mississippi River reported that the flow of the water there reversed for several hours.

The area remains seismically active and scientists believe another strong quake will impact the region again at some point in the future. Unfortunately, the science isn’t mature enough to tell whether that threat will arrive next week or in 50 years. Either way, with the population of New Madrid Seismic Zone huge compared to the sparsely populated area of the early 1800s, and tens of millions more living in an area that would experience significant ground shaking, there could be a very significant loss of life and property when another major quake strikes here again in the future.

The renewed activity around the New Madrid fault area does not appear to be related to an ongoing earthquake swarm in South Carolina. There, since December 2021, more than 40 earthquakes have rocked central South Carolina, with several stronger earthquakes felt and measured in recent days. Scientists say the distance between the New Madrid-area earthquakes and those of Elgin, South Carolina are too far apart to be related.

There have been other recent earthquakes in Tennessee and Alabama. While not directly related to each other, they are likely all part of the activity one would expect from the New Madrid Seismic Zone.