The Kilauea Volcano continues to erupt lava, illuminating the night sky over Hawaii Volcanoes National Park with a red glow. While lava continues to fill a crater within Kilauea, gas ejected from the eruption is making its way around the island raising concern well beyond the volcano’s summit. Changes in air quality and weather conditions could be possible far from the eruption site.

The Kilauea Volcano has been quiet since the end of the destructive 2018 lava flow from the volcano’s Lower East Rift Zone that wiped-off communities like Kapoho and Vacationland off the map. That changed on the night of December 20 when USGS scientists studying the volcano spotted a glow coming from the Kilauea Crater. A 4.4 earthquake later, the 2020 Eruption sequence kicked off, bringing an end to a nearly 2 year break in surface lava activity on Hawaii’s Big Island.

Fortunately, the lava is completely contained within a crater within the broader Kilauea caldera at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. According to USGS scientists, lava is ejecting from fissures inside the Halema’uma’u crater inside the caldera. While the lava there continues to rise, it has yet to reach the floor of the taller caldera. However, gas is rising from the eruption site.

Halema’uma’u crater was previously occupied by a growing lake of water. Formed after the 2018 eruption ended, the lake of different shades of green and brown eventually became dozens of feet deep. According to USGS, at the end of November, the lake measured 230 feet wide by 520 feet long. During Sunday night’s eruption, lava spilled down into the lake from three fissures, evaporating the lake completely.

When lava spilled into the water lake within the crater, it nearly instantly evaporated, sending a cloud of steam, volcanic gas, and other volcanic debris high into the sky. The initial eruption and explosion of steam was significant enough to be captured by the GOES-West weather satellite that monitors the weather over the Pacific and western United States.

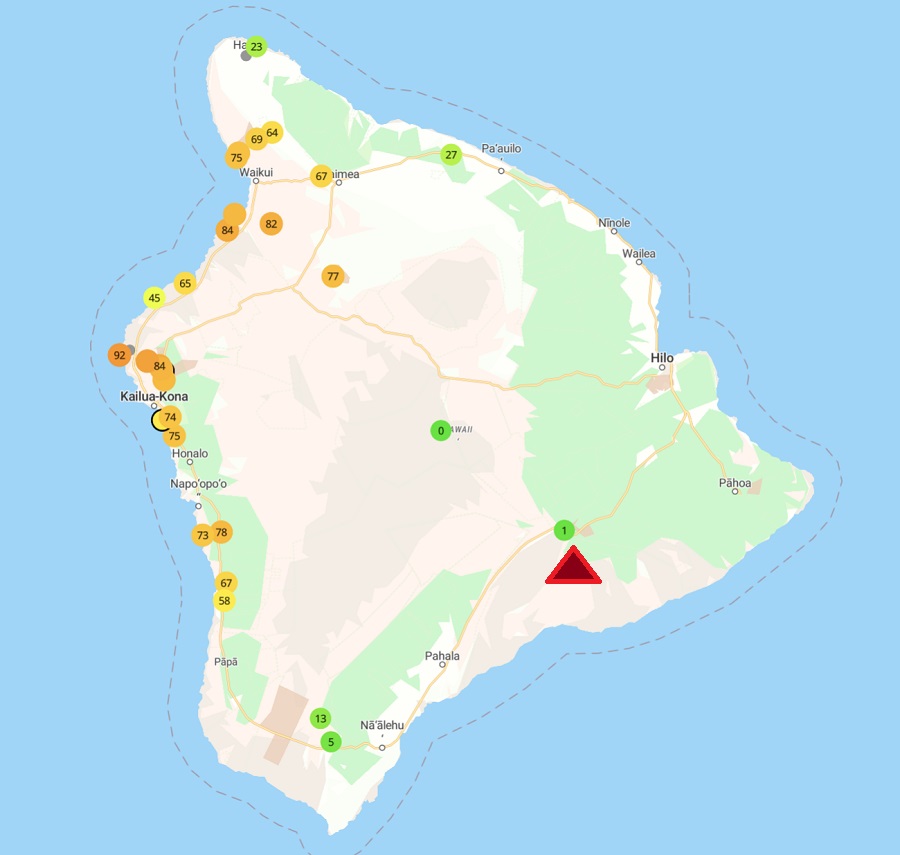

While the evaporation provided the most spectacular plume into the sky from the eruption site, a variety of gas bubbles up from the volcano into the atmosphere daily. Trade winds blowing from the east to the west blow the plume south and west over southern portions of the island; however, in the “wake” of the trade winds blowing across the high mountainous peaks of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the island, the plume tucks in along the west coast of Hawaii, trapped near the population center of Kailua-Kona.

These volcanic emissions create hazy air pollution known as “vog”. Vog consists primarily of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. As the sulfur dioxide gas mixes with UV light from the sun, oxygen, moisture, and other matter in the atmosphere, it converts to fine particles that scatter sunlight, causing a visible haze.

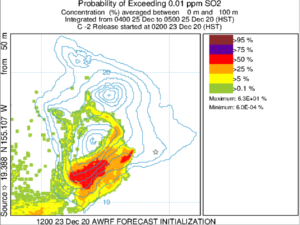

Similar to tracking weather systems and storms through computer forecast models, scientists use forecast models to track where particulate matter and sulfur dioxide gas travel once they leave the volcano. The School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa is one entity that takes the lead in forecasting the movement of this vog.

The Hawaii State Department of Health and the National Park Service also track volcanic pollutants through various sensors on the island of Hawaii. Careful attention is paid to sulfur dioxide and particulate matter of size 2.5 µm or less. Beyond obscuring visibility, these volcanic pollutants can also create conditions harmful to life.

Two days after the December 19 eruption, Randy Botti noticed the vog back in Kona. “After a 2 year respite, the vog was back and thick all day,” Botti told us. “I work at a car dealership; I guess the fact we’re all wearing masks anyway is a blessing,” Botti added, describing face coverings required anyway for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. “Starting to feel scratchy throats and watery eyes in the morning when there is no breeze,” Botti described the eruption’s early days. During the robust 2018 eruption of Kilauea’s Lower East Rift Zone, Botti purchased two air purifiers to improve air quality at his Kona condo.

Botti is also an owner of a PurpleAir device. Using a power outlet and a WiFi connection, PurpleAir sensors installed by people around the island are providing additional insights in the flow of vog around the island. Using laser particle counters to provide real-time measurement of PM1.0, PM2.5 and PM10, PurpleAir plots data in real time to the PurpleAir map.

Botti’s PurpleAir device is mounted inside; with the air purifiers turned on, people viewing the map can sees the drop of pollutants there compared to outdoor sensors deployed nearby outside in the community.

(See this important note about a product recall on certain PurpleAir devices.)

According to the Hawaii Department of Health, individuals with pre-existing respiratory conditions are the primary group at risk of experiencing health effects from vog exposures, but healthy people may also experience symptoms.

The Hawaii Department of Health adds that sulfur dioxide alone can be harmful to people. Physically-active asthmatics are most likely to experience serious health effects, with even short-term exposures causing bronchoconstriction (narrowing of the airways), which in turn creates asthma symptoms. Potential health effects increase as sulfur dioxide levels and/or breathing rates increase. When “unhealthy” levels are reached, even non-asthmatics may experience breathing difficulties. Other symptoms of sulfur dioxide exposure include eye, nose, throat, and/or skin irritation, coughing and/or phlegm, chest tightness and/or shortness of breath, and increased susceptibility to respiratory ailments. Some people also report fatigue or dizziness when exposed to sulfur dioxide. While even short-term exposure is connected to increased visits to emergency departments and hospital admissions for respiratory illnesses, long-term health effects of prolonged exposure to volcanic gases are still being studied.

Beyond negatively impacting human health, vog can also negatively impact agriculture directly and humans indirectly. Rain falling through acidic vog can become acid rain which can harm or kill plants and trees, contaminate household water supplies by leaching metals from building and plumbing materials in rooftop rainwater-catchment systems, and harm surfaces exposed to the elements, such as the paint on cars. USGS reports past eruptions have harmed livestock on Hawaii, while even degrading the metal fences that keep livestock contained on the ranches they graze.

On a bigger scale, the new eruption of Kilauea may also be able to alter the weather on the island. Kevin Kodama, Senior Service Hydrologist at the National Weather Service’s Honolulu office, described the impact vog has on the weather.

“Volcanic emissions will tend to hinder rainfall, due to the cloud microphysics and properties,” said Kodama. Too many volcanic aerosols in the air can inhibit the process by which moisture clings to nuclei in the atmosphere to create what eventually becomes rain drops and snow flakes. When Kilauea is active, it makes the ability to produce clouds and precipitation less efficient in areas influenced by those volcanic gasses.

In October, Kodama and the National Weather Service unveiled their “wet season” outlook for Hawaii, an extended forecast that examines projected conditions for the period from October to April in the Aloha State. At that time, Hawaii had no volcanic emissions.

“With the lack of volcanic emissions, conditions will return to normal or back to a normal type of regular rainfall,” Kodama said. “In the last couple of summers, on the Kona side of the Big Island, they’ve had pretty wet summers. Normally, the summer season is their (Kona area) wet season, but if you look at this past summer, they’ve had a very wet summer.”

However, with those volcanic emissions back, it remains to be seen whether or not the renewed volcanic activity on the island will impact the “wet season”, making it more dry than usual, especially where vog is greatest on Hawaii’s southern and western coasts.

While volcanic gas continues to rise from Kilauea, tourists are flocking to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park which surrounds the active volcano.

“The return of lava to the summit of Kīlauea is a natural wonder, but we need the public to be fully aware that we are in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and to recreate responsibly, maintain social distance and to wear a mask,” said Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park Superintendent Rhonda Loh. “We want to keep the park open for all to experience this new phase of volcanic activity, and we need visitors to follow safety guidelines that keep everyone safe. We continue to work with USGS scientists to receive the latest volcanic updates, and remind visitors that the eruptive activity and accessibility could change at any time,” Loh said.

View this post on Instagram

While the park is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, the Park Service warns that numerous hazards exist near Kilauea. “Volcanic eruptions can be hazardous and change at any time. Stay on marked trails and overlooks, and avoid earth cracks and cliff edges. Do not enter closed areas.” They add, “Hazardous volcanic gases are billowing out the crater and present a danger to everyone, especially people with heart or respiratory problems, infants, young children and pregnant women. ” While most of the hazardous gas is blowing up and away from most areas open to tourists, a sudden shift in wind direction could bring those gases into areas where visitors are.

“When air quality is poor, visitors should get in their vehicles, turn on the air conditioner, and go to another area not impacted by volcanic gas. There are no safe options for visitors to seek shelter indoors in the park due to the pandemic,” Loh said.

View this post on Instagram

The amount of pollutants erupting with the lava varies from day to day and scientists aren’t sure if the volumes will drastically change in the coming days or weeks. In the past, eruptions at Kilauea have lasted days and others have lasted years; the volume of lava and gas coming out is easy to monitor, but difficult to forecast.

According to USGS, in the early days of the December 2020 eruption, upwards of 40,000 tonnes of sulfur dioxide emissions were bubbling up with the lava. On the morning of December 27, rates dropped significantly down to about 5,500 tonnes/day. However, in the 2018 eruption, USGS says they measured the highest gas emission rates ever at Kilauea; in June and early July 2018, the emissions were around 200,000 tonnes/day. A tonne, also known as a metric ton, is equal to 1000 kg or 2,204.6 pounds.

While the amounts of emissions fluctuate, scientists continue to monitor the situation around-the-clock at Kilauea. But well beyond the borders of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, residents and scientists also have an eye to the sky to see how this latest eruption could impact health and weather in the coming days and weeks.

There is a “Bad Air Quality” sign inside @Volcanoes_NPS tonight, but the air near Wahinekapu at the edge of #Kilauea caldera is fresh, thanks to wind blowing the eruption’s plume away. Our pocket SO2 meter shows a clean 0.0 ppm reading. #HIwx #KilaueaEruption pic.twitter.com/BKzK45tZHD

— the Weatherboy (@theWeatherboy) December 22, 2020