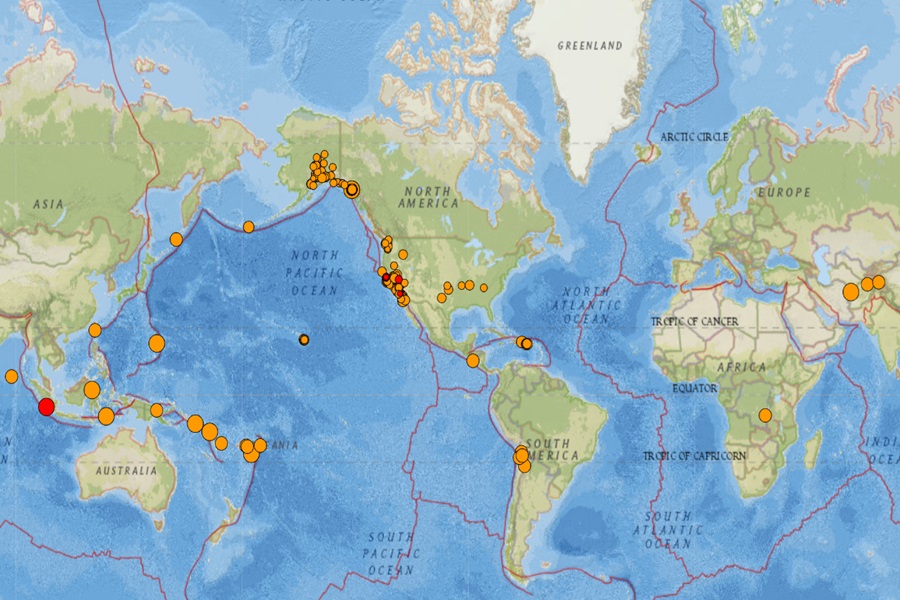

The world is a seismically active place, with USGS reporting 272 earthquakes around the globe over the last 24 hours. Out of these 272 quakes to rattle the Earth, those, 124 hit the continental United States. While the west coast is the most seismically active, including two mild quakes to rattle the San Francisco metro area, there have also been earthquakes across the southeastern United States.

According to the USGS, the volume and intensity of these earthquakes isn’t out of the norm.

According to long-term records maintained since around 1900, USGS says they expect about 16 major earthquakes in any given year. That includes 15 earthquakes in the magnitude 7 range and one earthquake magnitude 8.0 or greater. In the past 40-50 years, USGS records show that the long-term average number of major earthquakes has been exceeded about a dozen times. The year with the largest total was 2010, with 23 major earthquakes (greater than or equal to magnitude 7.0). In other years the total was well below the annual long-term average of 16 major earthquakes. 1989 only had 6 major earthquakes and 1988 only had 7.

Earthquakes occur along fault lines, cracks in Earth’s crust where tectonic plates meet. They occur where plates are subducting, spreading, slipping, or colliding. As the plates grind together, they get stuck and pressure builds up. Finally, the pressure between the plates is so great that they break loose in the form of an earthquake.

Much of this activity occurs along the west coast of the United States, where the Pacific Plate and North American Plate collide, creating fault lines with numerous quakes. The most famous of the faults is San Andreas, a fault that runs through much of California. However, earthquakes can happen throughout the U.S. too.

According to the South Carolina Emergency Management Division (SCEMD), there are approximately 10-15 earthquakes every year in South Carolina, with most not felt by residents; on average, only 3-5 are felt each year. Most of South Carolina’s earthquakes are located in the Middleton Place-Summerville Seismic Zone. The two most significant historical earthquakes to occur in South Carolina were the 1886 Charleston-Summerville quake and the 1913 Union County quake. The 1886 earthquake in Charleston was the most damaging earthquake to ever occur in the eastern United States; it was also the most destructive earthquake in the U.S. during the 19th century.

The 1886 earthquake struck at about 9:50 pm on August 31; it was estimated to have been rated a magnitude 6.9 – 7.3 seismic event. The earthquake was felt as far away as Boston, Massachusetts to the north, Chicago, Illinois and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to the northwest, and New Orleans, Louisiana to the south. The earthquake energy even traveled as far away as Cuba and Bermuda, where some shaking was felt too. The initial earthquake lasted about 45 seconds.

The 1886 Charleston earthquake was responsible for 60 deaths and over $190 million (in 2023 dollars) in damage. The area of major damage extended out 60-100 miles from the epicenter, with some structural damage even reported in central Alabama, Ohio, eastern Kentucky, southern Virginia, and western West Virginia from the initial quake.

A study published in 2008 in the Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering hypothesized that if such an earthquake were to strike the region today, it would lead to approximately 900 deaths, 44,000 injuries, and damages in excess of $20 billion in South Carolina alone.

The initial earthquake was followed by an aftershock 10 minutes later; over the first 24 hours, seven additional strong aftershocks hit. Over the following 30 years, a total of 435 aftershocks were measured.

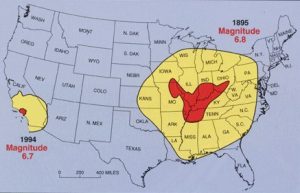

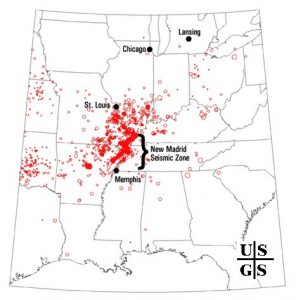

The Mississippi Valley is also home to extreme seismic activity. Authorities are concerned that people aren’t properly prepared for when a big earthquake will strike this region again. The matter of a larger destructive earthquake in this area is more of a matter of “when” rather than “if.” The NMSZ has a violent history that experts say will repeat itself, although no one is sure when it’ll happen.

December 16 marks the anniversary of the first of three major quakes to strike the United States during the winter of 1811-1812, a violent time in seismological history of the region that scientists say will be repeated again.

While the US West Coast is well known for its seismic faults and potent quakes, many aren’t aware that one of the largest quakes to strike the country actually occurred near the Mississippi River. On December 16, 1811, at roughly 2:15am, a powerful 8.1 quake rocked northeast Arkansas in what is now known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The earthquake was felt over much of the eastern United States, shaking people out of bed in places like New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, SC. The ground shook for an unbelievably long 1-3 minutes in areas hit hard by the quake, such as Nashville, TN and Louisville, KY. Ground movements were so violent near the epicenter that liquefaction of the ground was observed, with dirt and water thrown into the air by tens of feet. President James Madison and his wife Dolly felt the quake in the White House while church bells rang in Boston due to the shaking there.

But the quakes didn’t end there. From December 16, 1811 through to March of 1812, there were over 2,000 earthquakes reported in the central Midwest with 6,000-10,000 earthquakes located in the “Bootheel” of Missouri where the New Madid Seismic Zone is centered.

The second principal shock, a magnitude 7.8, occurred in Missouri weeks later on January 23, 1812, and the third, a 8.8, struck on February 7, 1812, along the Reelfoot fault in Missouri and Tennessee.

The main earthquakes and the intense aftershocks created significant damage and some loss of life, although lack of scientific tools and news gathering of that era weren’t able to capture the full magnitude of what had actually happened. Beyond shaking, the quakes also were responsible for triggering unusual natural phenomena in the area: earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake smog.

Residents in the Mississippi Valley reported they saw lights flashing from the ground. Scientists believe this phenomena was “seismoluminescence”; this light is generated when quartz crystals in the ground are squeezed. The “earthquake lights” were triggered during the primary quakes and strong aftershocks.

Water thrown up into the air from the ground, or the nearby Mississippi River, was also unusually warm. Scientists speculate that intense shaking and the resulting friction led to the water to heat, similar to the way a microwave oven stimulates molecules to shake and generate heat. Other scientists believe as the quartz crystals were squeezed, the light they emit also helped warm the water.

During the strong quakes, the skies turned so dark that residents claimed lit lamps didn’t help illuminate the area; they also said the air smelled bad and was hard to breathe. Scientists speculate this “earthquake smog” was caused by dust particles rising up from the surface, combining with the eruption of warm water molecules into the cold winter air. The result was a steamy, dusty cloud that cloaked the areas dealing with the quake.

The February earthquake was so intense that boaters on the Mississippi River reported that the flow of the water there reversed for several hours.

The area remains seismically active and scientists believe another strong quake will impact the region again at some point in the future. Unfortunately, the science isn’t mature enough to tell whether that threat will arrive next week or in 50 years. Either way, with the population of New Madrid Seismic Zone huge compared to the sparsely populated area of the early 1800s, and tens of millions more living in an area that would experience significant ground shaking, there could be a very significant loss of life and property when another major quake strikes here again in the future.