The USGS has just issued a new warning for Kilauea volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island, advising people that an explosive event may arrive soon at the main crater at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Perhaps a repeat of a 1924 explosive eruption, volcanologists are worried that water may mix with the hot magma creating a large explosion deep underground which would explode matter up and away a substantial distance from the Kilauea Caldera. The latest eruption in the East Rift Zone and lava levels inside Hawaii Volcanoes National Park has scientists concerned.

Halema‘uma‘u, the largest crater in Kīlauea Caldera was the site of more than 50 explosive events during a 2.5-week period in May 1924. The explosions were then, and remain today, the most powerful at Kīlauea since the early 19th century, throwing blocks weighing as much as 14 tons from the crater. Halema‘uma‘u doubled in diameter, deepened to about 1300 feet, and drastically changed in behavior. It wasn’t until 2009, some 85 years later, that lava returned to the crater in the form of a lava lake. The action in May 1924 was followed by the same events we see today: earthquake swarm and eruption in the volcano’s East Rift Zone.

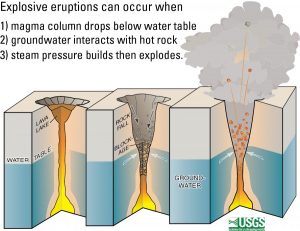

In an alert issued this morning, the USGS says, “The steady lowering of the lava lake in “Overlook crater” within Halemaʻumaʻu at the summit of Kīlauea Volcano has raised the potential for explosive eruptions in the coming weeks. If the lava column drops to the level of groundwater beneath Kīlauea Caldera, influx of water into the conduit could cause steam-driven explosions.” Steam driven explosions could be extremely dangerous; they add, “Debris expelled during such explosions could impact the area surrounding Halemaʻumaʻu and the Kīlauea summit. At this time, we cannot say with certainty that explosive activity will occur, how large the explosions could be, or how long such explosive activity could continue.” The USGS says Hawaii County Civil Defense will issue additional alerts should the explosion become imminent or underway.

With such an explosive event, there are three primary hazards: ballstic projectiles, ashfall, and gas.

According to the USGS, during steam-driven explosions, ballistic blocks up to 6 feet across could be thrown in all directions to a distance of a half mile or more. Such projectile blocks could weigh anywhere from a few pounds to several tons. One such projectile killed a man at the crater rim in the 1924 explosive event. Truman Taylor, a bookkeeper from Pahala sugar plantation, was near the rim of Halema’uma’u at the time of the 11:15 a.m. explosion on May 18. He was struck by a ballistic block, attempted to crawl away, but later died from his injuries. Smaller pebble-sized objects could be thrown much greater distances; a pebble-sized rock could be ejected several miles down-wind.

At this time, during the drawdown of the lava column inside the caldera, rockfalls from the steep walls of the Overlook crater impact the deep lava lake and produce small ash clouds. These clouds result in dustings of ash down-wind. Should steam-driven explosions begin, ash clouds will rise to greater elevations above ground. Minor ashfall could occur over much wider areas, even up to several tens of miles from Halemaʻumaʻu. In 1924, ash may have reached as high as 20,000 feet above sea level. By rising so high, upper-level winds such as the jet stream, could carry ash far away. When mixed with atmospheric moisture, a muddy ash could also fall, caking onto surfaces over a large area. In the case of the 1924 explosive event, small amounts of fine ash fell over a wide area as far north as North Hilo (Hakalau), in lower Puna, and as far south as Waiohinu.

Gas emitted during steam-drive explosions will be mainly steam, but will include some sulfur dioxide (SO2) as well. Currently, SO2 emissions remain elevated and within the current rift eruption zone, are extremely high. Additional sulfur dioxide in the air could be extremely harmful to both animal and plant life. When rained out of the air, the sulfur dioxide and rain will create extremely acid acid rain; such acid rain could burn skin and irritate soft tissue of the nose and lungs, could harm painted surfaces such as automobiles and homes, and kill plants and crops. Current winds around Hawaii’s Big Island are favorable for sulur dioxide to wrap around the southern and southwestern side of the island, threatening Kona’s large coffee crops. Even large macadamia nut farms could be negatively impacted by very acidic rain.