Russian troops invading the Ukraine today rushed into Pripyat, home of the infamous Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant which exploded in 1986. Ukrainian Presidential Advisor Mykhailo Podolyak told the Associated Press that Russian forces took control over the decommissioned nuclear power plant; authorities there said in the process of the violent attack in the area, shelling hit a radioactive waste repository at Chernobyl, increasing the amount of radiation in the area. Now scientists are busy watching for signs of any radioactive event unfolding, including tracking any hazardous radioactive cloud that could rise from the area and float through Europe and perhaps beyond.

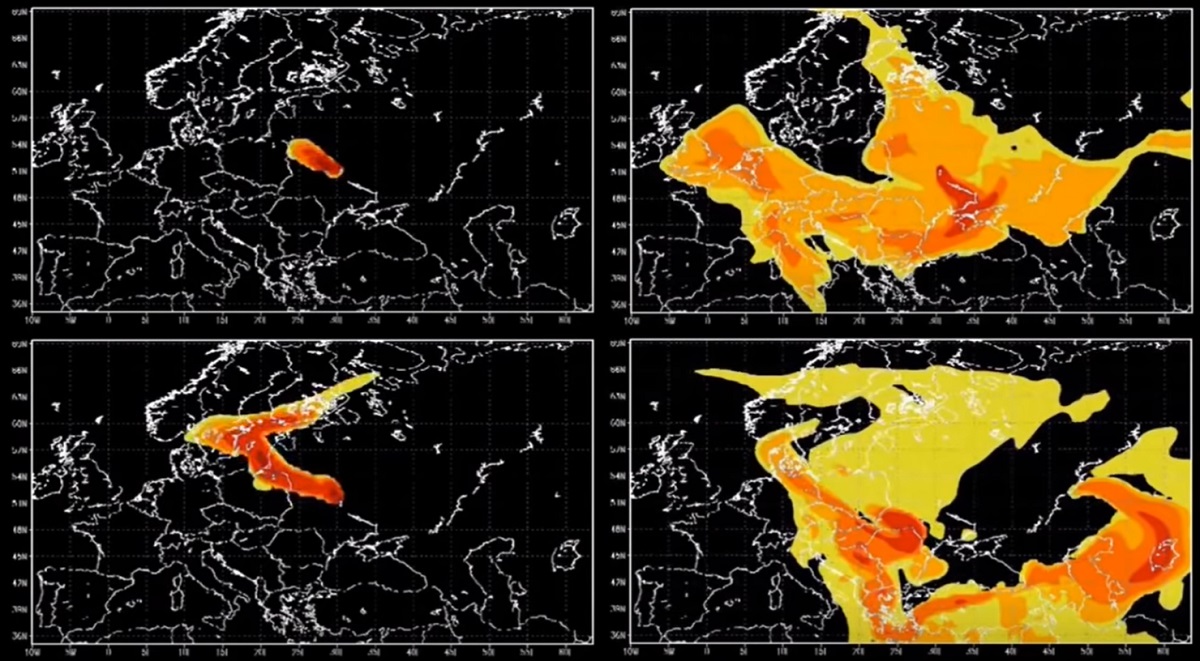

On April 26, 1986, through a series of failures during a safety drill, a reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant was destroyed by a violent explosion. The explosion sent radiation throughout Europe and the detection of radiation in Europe was the first sign that something had gone wrong at the then-USSR plant.

While the failed reactor is no longer burning, it and the nearby radioactive waste remains a grave threat to people near and around the plant. A 20-mile radius was drawn around the plant; referred to as the “exclusion zone”, this heavily contaminated area has been closed to human habitation since the 1986 disaster. While the plant was covered in concrete after the disaster to lock additional radioactive debris from leaving the area, it was observed to be breaking-down in the 1990s, allowing for radioactivity to leave the plant. Due to that, a new shelter was built and slid over the site to better confine radioactive matter; construction started in 2010 and was completed in 2019.

While a new shelter exists, the site and nearby radioactive waste containment areas need ongoing monitoring and service. With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the status of those important resources are unknown.

The Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says it has been informed by Ukraine that “unidentified armed forces” have taken control of the nuclear plant. IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi called for “maximum restraint” to avoid actions that could put Ukraine’s nuclear facilities at risk.

“In line with its mandate, the IAEA is closely monitoring developments in Ukraine with a special focus on the safety and security of its nuclear power plants and other nuclear-related facilities,” he said in a statement.

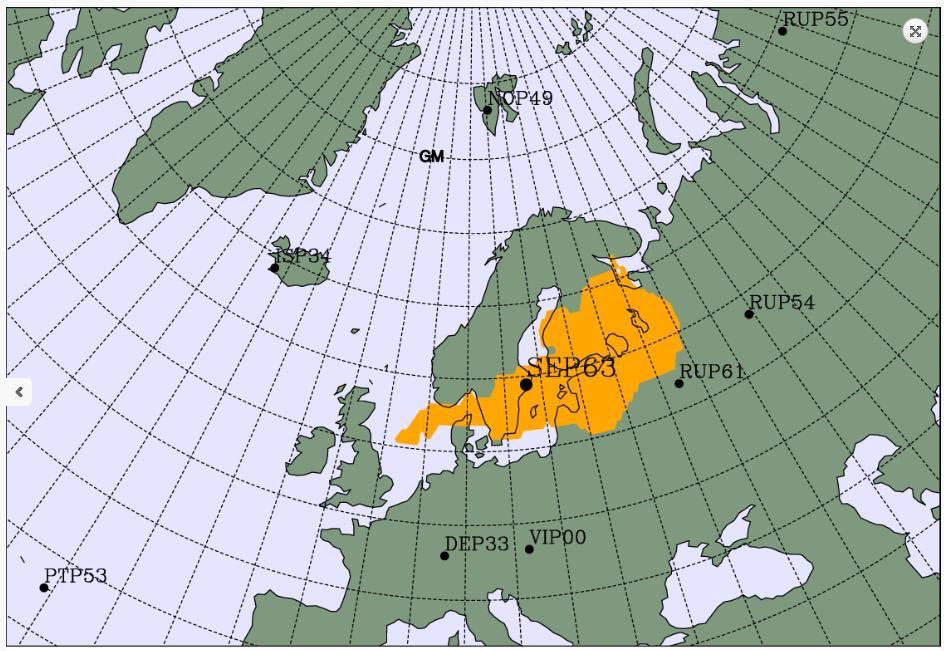

The invasion into the Chernobyl site isn’t Russia’s first foray in nuclear incidents in Europe. In June 2020, a mysterious radioactive cloud drifted into Europe. At that time, Lassina Zerbo, the Executive Secretary of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), shared news that sensors in Sweden have detected three isotopes typically associated with nuclear fission.

“These isotopes are most likely from a civil source. We are able to indicate the likely region of the source, but it’s outside the CTBTO’s mandate to identify the exact origin,” Tweeted Zerbo after the radioactive cloud was detected.

Within this region are two nuclear power plants: Loviisan Voimalaitos in Finland and Leningradskaya Aes in Russia. The Finland plant reported no unusual events at their facility while Russia never shared details about there. A week earlier from this incident, iodine-131 was measured at the two air filter stations Svanhovd and Viksjøfjell near Kirkenes , which is a short distance from Norway’s border to Russia’s Kola Peninsula.

Scientists monitoring these sensors that tipped-off the presence of an incident in 2020 and the larger original Chernobyl disaster in 1986 will be busy tracking any sign of radioactive activity coming from Ukraine now in the hours and days ahead.

Radioactivity from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster eventually did make its way around the globe, blown about by jet streams and air currents around the Earth’s atmosphere. While radioactivity levels were lethal at the exploded reactor, they became diluted as they moved away from the primary disaster site into other countries and continents. However, if an incident goes unchecked inside Ukraine now, its possible dangerous radiation could spread into NATO member countries in Europe and perhaps beyond.