A Research Letter published by doctors today in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) “Internal Medicine” publication suggests that asthma attacks associated with thunderstorms can hit victims well before the storms do. A team of study authors, led by doctors Eric Zou, PhD , Christopher Worsham, MD, and Nolan Miller, PhD, explored the relationship between thunderstorm activity and hospital emergency room visits for respiratory illnesses among older adults.

An asthma attack restricts the passage of air around one’s bronchial tubes where air travels in and out of lungs, making it hard to breathe. While a mild asthma attack might only last a few minutes, a stronger one could last hours or even days without medical treatment.

When thunderstorms approach an area with lots of airborne particles, such as pollen, they too could bring about asthma attacks. The moisture and air flow associated with storms can help disperse particles around the surface where people breathe, bringing about an asthma attack.

Signs and symptoms of an asthma attack include shortness of breath, a tight feeling in one’s chest, fast breathing, and coughing and wheezing.

Study scientists reviewed a variety of records to produce their findings. NOAA data on thunderstorms from 1999 to 2012 was explored as were insurance claims and comorbidity data of Medicare patients aged 65 and over, focusing specifically on emergency room visits due to respiratory illness.

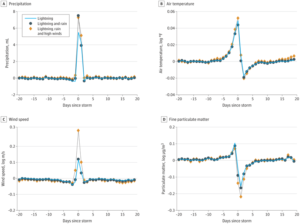

Using a statistical model to help crunch the math, the doctors explored correlations between the weather and health records. They discovered that before a thunderstorm arrived, the air temperature and concentrations of particulate matter in the air surged. This particulate matter includes pollen, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide. Both temperature and particulate matter leveled-off when the storm arrived, and continued to drop as the storm moved through the area being examined. Based on their analysis, the number of visits to the emergency room surged in the three days before a storm arrived.

Prior to this study, it was assumed that pollen grains that “erupt” when they get wet would trigger asthma in a patient during the storm. However, this study showed that emergency room visits peaked before the storm’s arrival, suggesting that pollen particle release from precipitation in a storm was not the dominant mechanism. The authors warned, “A limitation of this study is that it may not generalize to younger populations for which allergeic asthma is common,” suggesting that the study’s skew on older Americans and their Medicaid data may skew the results too.

“Our findings suggest antecedent rises in particulate matter concentration and temperature may be the dominant mechanism of thunderstorm-associated acute respiratory disease in older Americans, which may contribute to strain on the health care system as storm activity increases with rising global temperatures.” The full study can be viewed here: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2769087