The Department of Health in Hawaii has informed the public that the air quality has reached thresholds deemed “harmful” several times in December; all were caused by the ongoing Kilauea Volcano Eruption. The release by the Department of Health of this news is required by U.S. Federal Law under the Clean Air Act.

The Clean Air Act, initially implemented by the Nixon administration in 1970 and last updated and amended in 1990, had the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for pollutants considered harmful to public health and the environment. There are two types of national air quality standards: primary and secondary. Primary standards provide general public health protection, especially with sensitive groups, while secondary standards provide a level of protection for the rest of the general public while also highlighting potential harm to animals, crops, vegetation, and even buildings. While sensitive populations like asthmatics, children, and the elderly can be harmed by poor air quality, poor air quality can also harm inanimate objects like paint on cars and buildings, metal roofs used to collect rain water, and more.

The EPA has set NAAQS standards for 6 primary pollutants: carbon monoxide, lead, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particle pollution (PM), and sulfur dioxide.

According to the Hawaii State Department of Health, standard limits were exceeded for sulfur dioxide in the Hawaii communities of Pahala, Ocean View, and Kona, In all cases, the Kilauea volcano was blamed for the excessive pollutant in the air.

The first violation occurred on December 21 at Pahala on the Big Island of Hawaii. While the standard limit for sulfur dioxide pollution is 0.075 parts per million (ppm) per 1 hour period, a reading more than 3 times greater than that of 0.240 parts per million was observed during the 10-11 hour on the 21st. Pahala continued to break the safe standard limits on December 22, December 24, December 25, December 26, December 27, December 28, and December 29.

The worst violation occurred in the community of Ocean View located on the south side of Hawaii’s Big Island; as with Pahala, numerous violations were recorded in Ocean View, but the worst happened on Christmas Eve. While the 1 hour average limit is 0.075 ppm, Ocean View registered a 1.981 ppm reading between 7 and 8 am; such a reading is more than 25 times the limit set by the EPA considered “safe”. Limits for 3 hour and 24 hour exposures were also exceeded in Ocean View on Christmas Eve.

Kona, a city located on the west side of Hawaii’s Big Island, also saw the NAAQS exceeded on Christmas Eve. Between 10 and 11am, the amount of sulfur dioxide observed in the air rose to 0.154 ppm, more than double the 0.075 limit.

In all, the Hawaii State Department of Health reported 15 instances from December 21 through December 29 that the National Ambient Air Quality Standards were exceeded.

In comparison, zero reports of sulfur dioxide pollution exceeding NAAQS were reported at all earlier in 2020 or at all in 2019. In fact, only once in 2019 were NAAQS exceeded in Hawaii. That occured on August 1 when a wildfire on Maui caused PM to exceed the 24 hour average standard of 35 µg/m3 by getting up to 40.5 µg/m3.

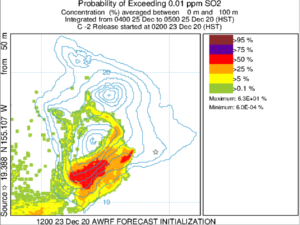

Fortunately, the current eruption is contained within a crater inside of Kilauea’s caldera inside Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. While the lava is contained there and is of no threat to any nearby communities for now, gas from the eruption is a problem for a large part of the state. A variety of gas bubbles up from the volcano into the atmosphere daily. Trade winds blowing from the east to the west blow the plume south and west over southern portions of the island; however, in the “wake” of the trade winds blowing across the high mountainous peaks of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the island, the plume tucks in along the west coast of Hawaii, trapped near the population center of Kailua-Kona.

These volcanic emissions create hazy air pollution known as “vog”. Vog consists primarily of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. As the sulfur dioxide gas mixes with UV light from the sun, oxygen, moisture, and other matter in the atmosphere, it converts to fine particles that scatter sunlight, causing a visible haze.

Two days after the December 19 eruption, Randy Botti noticed the vog back in Kona. “After a 2 year respite, the vog was back and thick all day,” Botti told us. “I work at a car dealership; I guess the fact we’re all wearing masks anyway is a blessing,” Botti added, describing face coverings required anyway for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. “Starting to feel scratchy throats and watery eyes in the morning when there is no breeze,” Botti described the eruption’s early days. During the robust 2018 eruption of Kilauea’s Lower East Rift Zone, Botti purchased two air purifiers to improve air quality at his Kona condo.

Botti is also an owner of a PurpleAir device. Using a power outlet and a WiFi connection, PurpleAir sensors installed by people around the island are providing additional insights in the flow of vog around the island. Using laser particle counters to provide real-time measurement of PM1.0, PM2.5 and PM10, PurpleAir plots data in real time to the PurpleAir map.

Botti’s PurpleAir device is mounted inside; with the air purifiers turned on, people viewing the map can sees the drop of pollutants there compared to outdoor sensors deployed nearby outside in the community.

According to the Hawaii Department of Health, individuals with pre-existing respiratory conditions are the primary group at risk of experiencing health effects from vog exposures, but healthy people may also experience symptoms.

The Hawaii Department of Health adds that sulfur dioxide alone can be harmful to people. Physically-active asthmatics are most likely to experience serious health effects, with even short-term exposures causing bronchoconstriction (narrowing of the airways), which in turn creates asthma symptoms. Potential health effects increase as sulfur dioxide levels and/or breathing rates increase. When “unhealthy” levels are reached, even non-asthmatics may experience breathing difficulties. Other symptoms of sulfur dioxide exposure include eye, nose, throat, and/or skin irritation, coughing and/or phlegm, chest tightness and/or shortness of breath, and increased susceptibility to respiratory ailments. Some people also report fatigue or dizziness when exposed to sulfur dioxide. While even short-term exposure is connected to increased visits to emergency departments and hospital admissions for respiratory illnesses, long-term health effects of prolonged exposure to volcanic gases are still being studied.

Fortunately, it appears the Kilauea volcano is emitting significantly less harmful gas than it was earlier in this latest eruption. According to USGS, in the early days of the December 2020 eruption, upwards of 40,000 tonnes of sulfur dioxide emissions were bubbling up with the lava. On the morning of December 27, rates dropped significantly down to about 5,500 tonnes/day. On December 31, USGS reported that emissions of sulfur dioxide further dropped to 3,800 tonnes/day in the previous day. A tonne, also known as a metric ton, is equal to 1000 kg or 2,204.6 pounds.

While the air quality will be dependent on eruption activity, the 2020-2021 eruption event isn’t emitting nearly as much gas that the last eruption event, in 2018, emitted. USGS says they measured the highest gas emission rates ever at Kilauea in that event; in June and early July 2018, the emissions were around 200,000 tonnes/day.