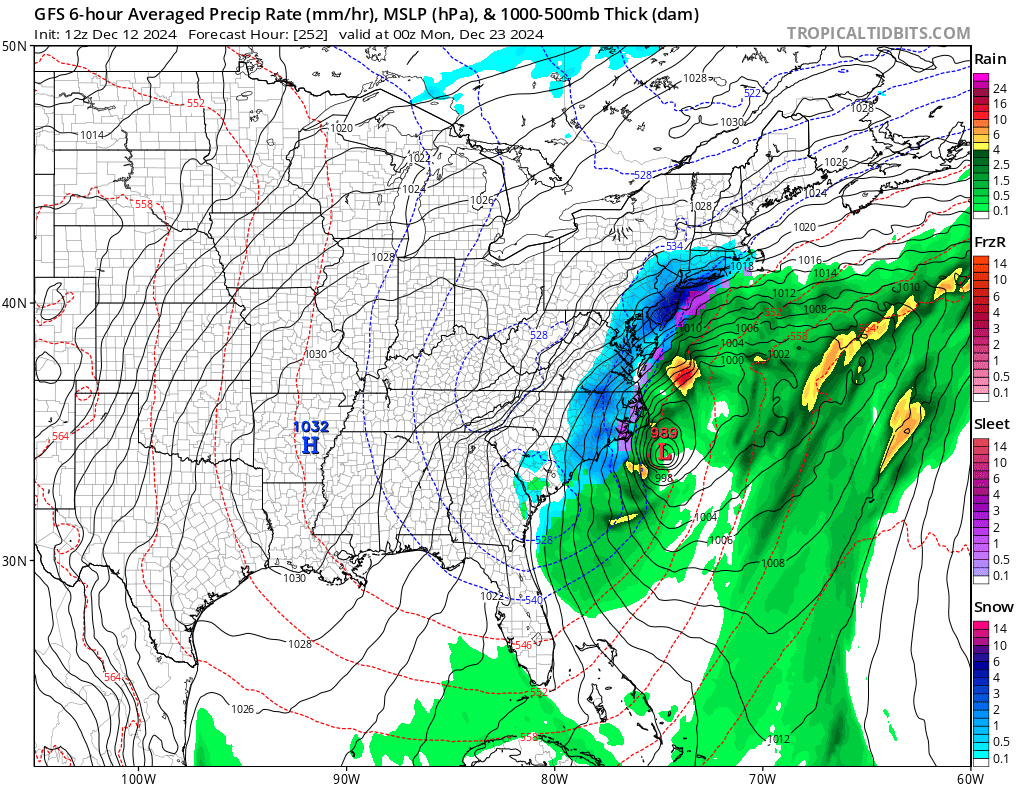

The American GFS forecast model’s afternoon run appears to be dreaming of a “White Christmas” for portions of the East Coast, suggesting a coastal storm would dump a considerable amount of snow along a large part of the coast from the Carolinas to New England. However, this single afternoon run could just be a dream not rooted in too much meteorological fact.

A leading computer forecast models used by meteorologists to aid with their weather forecasting is suggesting the possibility of a hefty coastal snowstorm on December 23. It shows an area of low pressure rapidly intensifying off of the Carolina coast; with plenty of cold air to work with, it drops snow as far south as South and North Carolina to as far north as Maine and Vermont. If this model run were to verify, southern New Jersey would see the most snow, with more than 2 feet possible along the Jersey Shore, points south of I-195, and towns just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. Elsewhere would see significant snow too, with several inches possible from North Carolina to Maine. But that is all a big if!

The GFS and ECMWF are among many computer models meteorologists use to assist in weather forecasting. While meteorologists have many tools at their disposal to create weather forecasts, two primary global forecast models they do use are the ECMWF from Europe and the GFS from the United States. While the models share a lot of the same initial data, they differ with how they digest that data and compute possible outcomes. One is better than the other in some scenarios, while the opposite is true in others. No model is “right” all the time. Beyond the ECMWF and GFS models, there are numerous other models from other countries, other academic institutions, and private industry that are also considered when making a forecast.

For such a snowstorm to unfold as the afternoon run of the GFS shows, conditions would need to be just right: there would need to be an ample supply of cold air along the coast, the jet stream and overall atmospheric flow would need to produce a perfect storm track, and the low pressure system would need to explosively grow along the Carolina coast. At this point, it is unlikely all of those ingredients would perfectly align. However, it is possible. But forecast model accuracy this far out in a dynamic, evolving weather pattern isn’t great and it is likely future model output will be different from today’s run that produces heavy snow.

In fact, an evening run of the same computer forecast model isn’t calling for pre-Christmas snow; instead, it has a wind-whipped rain storm moving up the coastal plain around December 20 and then brings in dry weather into the Christmas holiday.

Other models also disagree with the afternoon GFS projection. The latest ECMWF suggests a light snow event for the I-95 corridor north of Washington, DC, including the cities of Philadelphia and New York. However, as with the GFS, other runs from the ECMWF have offered up different solutions.

When there is a lack of run to run consistency by the forecast models and/or poor agreement across the different kind of forecast models, meteorologists confidence level in such computer output remains low.

While meteorologists know the climatological odds of a White Christmas this year, it is simply too soon to say with certainty what the weather will be in the days ahead of Christmas –for now.