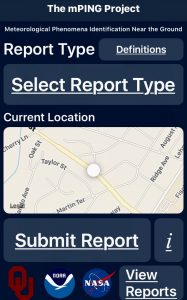

With the advent of smart phones, a new term has spread that describes every day people who can help scientists, including meteorologists. This term is “citizen scientist” and is an apt description of anyone who has downloaded an app on their smartphone called mPING.

Since its launch in December 2012, mPING (meteorological Phenomena Identification Near the Ground) has received over a million weather reports from over 90,000 individual users on U.S.-based weather events including rain, snow, ice, wind, hail, tornadoes, floods, landslides, fog and dust storms. These reports are used to improve forecasts related to road maintenance, aviation operations and public warnings.

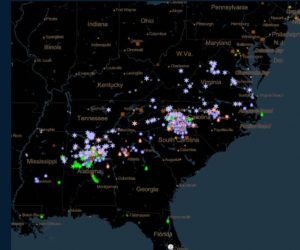

NOAA National Weather Service (NWS) forecasters are now using data from citizen scientists using the mPING app to keep apprised of the latest goings on in your backyard. For example, the mPING app was used by thousands of people to keep National Weather Service meteorologists up to date on precipitation type and amounts during the recent winter storm on Friday and Saturday December 8-9th that affected areas from Texas, and the Deep South to the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions.

NWS meteorologist Justin Pullin from the Tallahassee, FL office uses data from the app. “We do have a file set up for our workstations where we are able to use mPING. I personally use it, mainly for any winter weather situations that may arise and I’ll plug in a report that I personally observe and I will also monitor the interactive map at work for any hail or winter weather reports that may come in.” Pullin added,”I found mPING to be useful when I worked in the Las Vegas NWS office to determine if radar echoes of rain were reaching the ground.”

Seth Warthen, a meteorologist from the Lake Charles, LA NWS office, said mPING was used during the December 8th storm but had limited value in his area, “Because the rain/snow transition was fairly clean, quick, and identifiable through radar/surface obs, and by the time a co-worker began looking at mPING, the entire forecast area had already transitioned to snow. I was in a little bit earlier in the morning while the transition was taking place, but at that time in the morning the amount of mPING reports we were receiving were quite low, and really for the entirety of the event we only received a handful of reports anyways.”

Warthen does envision a scenario where mPING could provide significant value. “I could definitely see times that mPING reports would add more operationally significant value. A winter storm event in which the changeover is much more sloppy, or something like a severe event where there may be uncertainty if a storm is producing severe criteria hail. Those are at least a couple examples I could see the mPING reports being utilized a bit more.”

The ability to submit and display the data acquired from citizen scientists using their mPING app in other, independent applications is now possible as well. Television and radio stations, as well as private weather companies, have the opportunity to build the ability to submit and display mPING reports in their own branded applications, making the information available to their listeners, watchers and clients in new ways.

“These are exciting times!”, said Kim Elmore, Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMSS) research scientist working at the National Severe Storms Laboratory(NSSL). Elmore led the project and developed the app together with CIMMS scientists Jeff Brogden and Zac Flamig, The NSSL is a federal research laboratory under NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research and is located in Norman, OK. The NSSL has a strategic research partnership with CIMMS and the University of Oklahoma. CIMMS enables NSSL and university scientists to collaborate on research areas of mutual interest and facilitates the participation of students and visiting scientists.

Elmore is excited by what the citizen scientist data captured will do for the science. “The improvements make the app even more useful for researchers and forecasters as well as anyone who wants to know about the weather.” Elmore expanded; “Two important applications involved with mPING are developing a more accurate winter weather radar algorithm and determining which thunderstorms contain hail,” said Elmore. “The former has a wide range of uses, from operational meteorologists to power companies to the aviation industry. mPING has a use as we can compare what the winter weather radar says what should be falling from the sky and compare it to what mPING observations are saying is actually falling. In that way we can coax and massage the math involved with the algorithms used in the winter weather radar and improve the radar’s accuracy. With the latter, agricultural and travel industries need to know which thunderstorms have hail in them. In fact, with the help of mPING observations and field meteorologists, we have found than an average of 1 in every 5 thunderstorms contains hail in an area of the U.S. bordered by the Rockies to the west and the Appalachians to the east. Giving more advance warning time to farmers and Department of Transportations can help these two parties save crops and lives respectively.”

The mPING app has been getting rave reviews from a wide variety of sources. It was included in Scientific American’s list of “8 Apps That Turn Citizens into Scientists,” and the White House’s “Federal Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing Toolkit.” The official web page for mPING can be found here. The app is available in both the iOS App Store and Android Google Play store for free.

mPing joins another citizen science app in the store: Aurorasaurus. The Aurorasaurus app allows citizen scientists to share updates and images when the Northern Lights are visible; when aurora activity is visible in your area, an alert is triggered to app users.