Night sky observers will have a special treat this week: debris from Halley’s Comet’s tail will set the stage for a meteor shower which should delight the naked eye with streaks of shooting stars. According to NASA, Eta Aquarid meteors are known for their speed. Traveling at about 148,000 mph into the Earth’s atmosphere, fast meteors can leave glowing “trains” which last for several seconds to minutes. These trains are really incandescent bits of debris in the wake of the meteor. In general, 30 Eta Aquarid meteors can be seen per hour during their peak.

The pieces of space debris that interact with the Earth’s atmosphere to create the Eta Aquarids originate from Halley’s Comet. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory reports that each time that Halley returns to the inner solar system, its nucleus sheds a layer of ice and rock into space. The dust grains eventually become the Eta Aquarids in May and the Orionids in October if they collide with Earth’s atmosphere.

While debris from the comet will light up the night sky this week, don’t expect to see Halley’s Comet itself for a while. Halley takes about 76 years to orbit the sun once. The last time Halley was seen by casual observers was in 1986; it won’t enter the inner solar system again until 2061.

While the comet won’t be on display for another 40 years, the Eta Aquarids should put on a good show around Earth. The best viewing of the most meteors should be before dawn on Wednesday, May 5; however, the meteor shower should begin on May 4 and linger through to May 6. The pre-dawn hours in both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere is the best time to view; of the hemispheres, the Southern Hemisphere will have better odds of seeing shooting stars than the Northern Hemisphere.

The best viewing site is far away from sources of light pollution: city and street lights can block out the faint streaks that would be visible in an otherwise clear, dark night. Astronomers recommend that observers lie flat on their back with their feet facing east. As you look up in the clear, dark sky, your eyes should acclimate to the low light conditions and you should be able to see the meteors streak across the night sky. Of course, in addition to being in an area free of light pollution, you also need to be in an area free of clouds. (See local forecasts for your area to see if the sky will be cloud-free in your viewing area here.)

A meteor is a space rock—or meteoroid—that enters Earth’s atmosphere. As the space rock falls toward Earth, the resistance of the air on the rock makes it extremely hot, making a shooting star visible in the sky, That bright streak is not actually the rock, but rather the glowing hot air as the hot rock zips through the atmosphere.

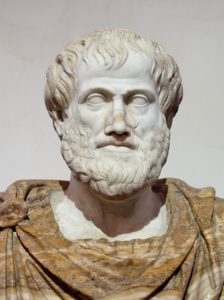

While the meteor shower will be interesting to meteorologists and non-meteorologists alike, meteors actually have nothing to do with the weather. The term “meteorology” likely originated in 340 BC when the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote a book on natural philosophy entitled “Meteorologica”. This philosophical work included knowledge of what was known about precipitation, lightning, thunder, geography, chemistry, and astronomy. The manuscript was called “Meteorologica” because in those times, any particle which fell from the sky was called a meteor. Today, astronomers and other space scientists study extraterrestrial meteors while meteorologists study so-called “hydrometeors” which are particles of water and ice in the atmosphere. Other than that ancient link thanks to Aristotle, there are no physical links between meteor showers and weather on Earth.