Computer forecast models, such as the American GFS and the European ECMWF, each show snow coming to portions of the Mid Atlantic and Northeast, but they completely disagree with each other how and when such storms will materialize. Until the forecast models come in better agreement with each other and there is more run-to-run consistency within their respective outputs, confidence is low in their suggested solutions for now.

The GFS and ECMWF are among many computer models meteorologists use to assist in weather forecasting. While meteorologists have many tools at their disposal to create weather forecasts, two primary global forecast models they do use are the ECMWF from Europe and the GFS from the United States. While the models share a lot of the same initial data, they differ with how they digest that data and compute possible outcomes. One is better than the other in some scenarios, while the opposite is true in others. No model is “right” all the time. Beyond the ECMWF and GFS models, there are numerous other models from other countries, other academic institutions, and private industry that are also considered when making a forecast.

For the second half of December and most of January, both major global forecast models have been adamant about keeping traditional winter weather out of the Eastern U.S.. With storm after storm hitting California, the jet stream has moved across the country in mainly a zonal fashion, quickly bringing storms from west to east without much chance for amplification or coastal regeneration. Extended guidance has suggested that pattern would change in February, but not global guidance is suggesting that may happen as soon as a week or two from now.

Today, the global model from Europe wants to trend things colder and sooner than its American counterpart.

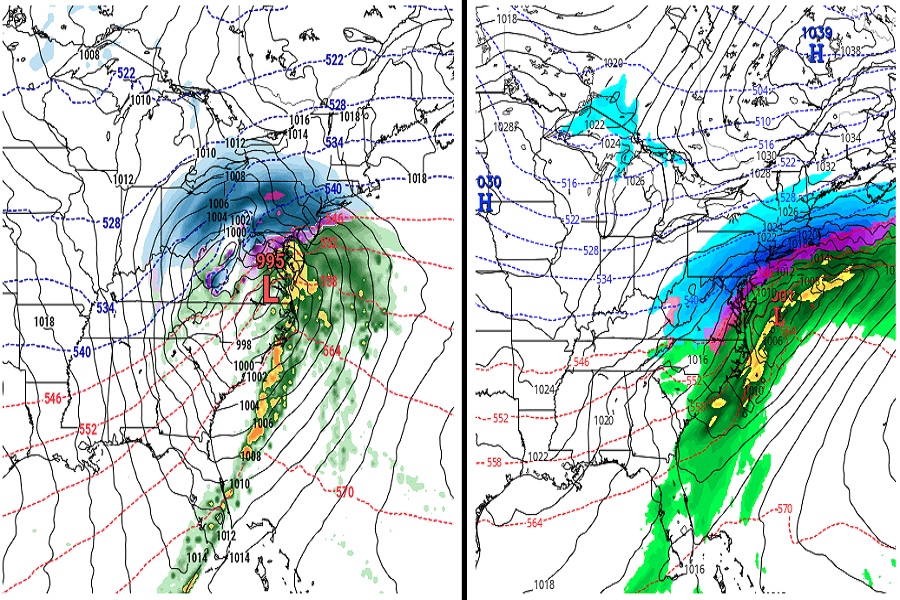

The ECMWF shows an area of low pressure moving through the Mid Atlantic and Northeast on January 23. While colder than other recent storms to impact the northeast, the forecast model suggests snow will be confined to areas well north and west of the I-95 corridor. Some snow could be especially significant in northern New England from this first storm. More importantly, as this storm departs late on the 23rd and 24th, it helps pull down more cold air from Canada into the Mid Atlantic. This in turn sets the stage for a snowier storm on the 25th, which would bring accumulating snow along and to the north of the I-95 corridor from Washington, DC to Boston. It would also bring wind-whipped heavy snow to much of New England on the 26th.

The GFS provides warmer solutions until February. The American model closely resembles the European for the January 23 forecast solution, albeit a tad warmer. Unlike the European model, the American model doesn’t have cold air from Canada filter in behind this system. Instead, it drives the next system, around January 25, up into the Great Lakes, pulling milder air up much of the coastal plain of the U.S. East Coast. Because of that, that storm brings mainly rain to the northeast. But it does wrap cold air behind that system, setting the stage for a more traditional I-95 snowstorm around February 2.

It is still far too soon to know which model is headed in the right direction. But after many weeks where there was no chance of winter-like weather for many, that appears to be changing in the coming days and weeks.