Hawaii is shaking; more than 100 earthquakes have struck the Big Island of Hawaii over the last 24 hours, with a new quake striking the volcanic island every few minutes. According to USGS, elevated unrest and increased seismicity began south of Kilauea’s summit yesterday, December 29, around 1:10 pm local time, and continues today. Kilauea is not yet erupting, but that may change in the near future.

The seismicity followed a sharp increase in the rate of inflation on the Sand Hill tiltmeter that began at 12:30 pm and is continuing. As magma accumulates in an underground reservoir before an eruption, the ground surface typically swells in a process geologists refer to as inflation. Likewise, as magma leaves the reservoir, potentially to erupt, the ground above the reservoir subsides and this is called deflation.

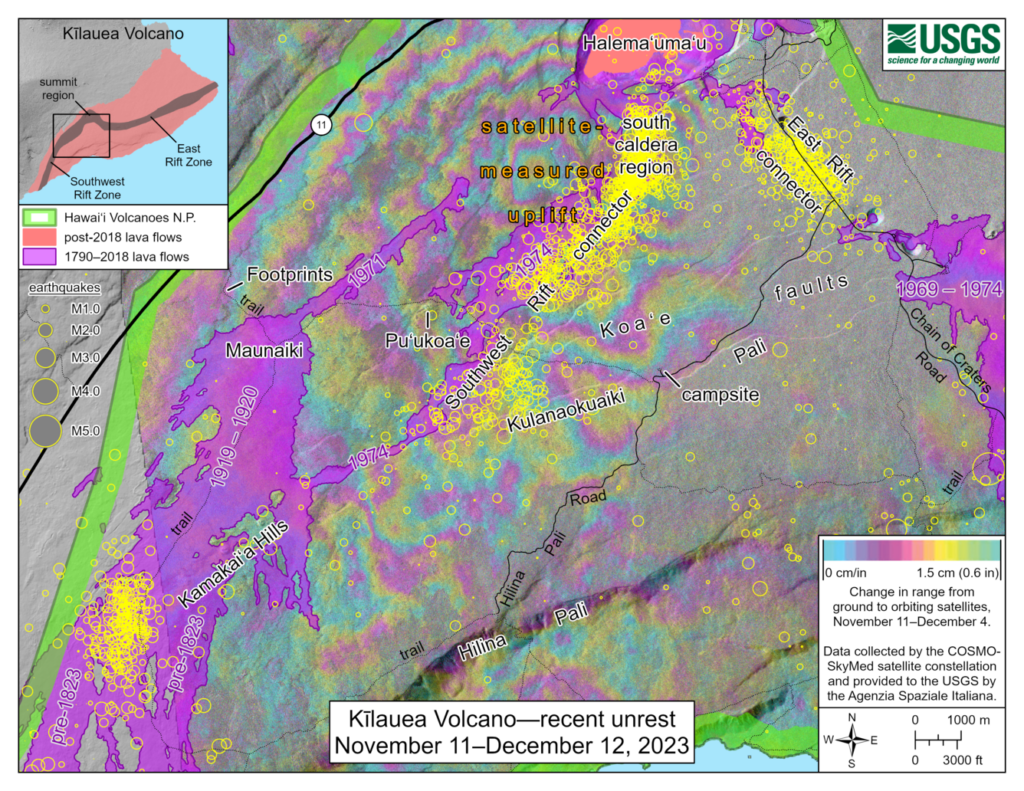

The increased seismicity began just to the south of Halemaʻumaʻu and has progressively included a larger region to the south of the caldera about 1–2.5 miles south of Halema‘uma‘u crater at Kilauea’s summit. Most of the seismicity is occurring at depths of 1/2 to 2 miles with magnitudes ranging from a maximum of 2.5 to less than 1. Between 1 pm and 7 pm last night, there were over 80 locatable earthquakes in this region alone along with many smaller earthquakes.

The Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO) of the USGS warns, “The summit of Kilauea remains at a high level of inflation and eruptive activity at the summit is possible with little or no warning.”

“Earthquake swarms like this can precede eruptions, but there is no lateral or upward migration of earthquakes that would suggest magma is moving toward the surface at this time. There are currently no signs of an imminent eruption at Kilauea, but the volcano’s summit region remains unsettled, with a high level of inflation and continued seismic activity,” wrote HVO in an update. They added, ” HVO continues to closely monitor Kīlauea volcano, watching for any signs of accelerated rates of earthquakes or ground deformation, or signs of shallowing earthquake locations, which usually precede a new outbreak of lava or propagating dike. We are also closely monitoring gas emissions and webcam imagery. ”

The most recent eruption at Kilauea summit ended on September 16, 2023, but was followed by a significant intrusion to the southwest of Kīlauea caldera. Seismicity has waxed and waned since then alternating between the southwest area, the south end of the caldera, and the upper East Rift Zone. Most recent seismicity has alternated between the summit caldera and the upper East Rift Zone.

The Big Island of Hawaii has seen elevated earthquake activity in recent weeks, although the frequency seen over the last 24 hours is new. Over the last 30 days, there have been 741 earthquakes of a magnitude 0.2 or greater.

Just days ago, on December 28, a moderate earthquake struck southeast of the town of Pahala, south of Kilauea’s summit. On Thursday, December 28, 3:16 pm, the magnitude-4.4 earthquake occurred 4 miles southeast of Pahala at a depth of 8 miles below sea level. This was the second strongest earthquake to strike Hawaii in the last 30 days. According to HVO, that earthquake had no apparent impact on either Mauna Loa or Kilauea volcanoes. According to USGS scientists, this particular earthquake appears to be the result of faulting on the offshore section of Kilauea’s Southwest Rift Zone. While the earthquake was felt at Kīlauea’s summit, it did not cause any changes in seismicity or deformation there.

A stronger magnitude 5.1 earthquake struck on December 4. Centered near Kilauea’s summit, that earthquake was felt throughout the Big Island of Hawaii and portions of eastern Maui.

Eruptions in Hawaii create numerous hazards: beyond the possibility of exploding rocks and lava at the time of initial eruption, lava flows could be destructive. In addition to releasing lava to the surface, volcanoes can also emit toxic gasses.

These volcanic emissions create hazy air pollution known as “vog”. Vog consists primarily of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. As the sulfur dioxide gas mixes with UV light from the sun, oxygen, moisture, and other matter in the atmosphere, it converts to fine particles that scatter sunlight, causing a visible haze.

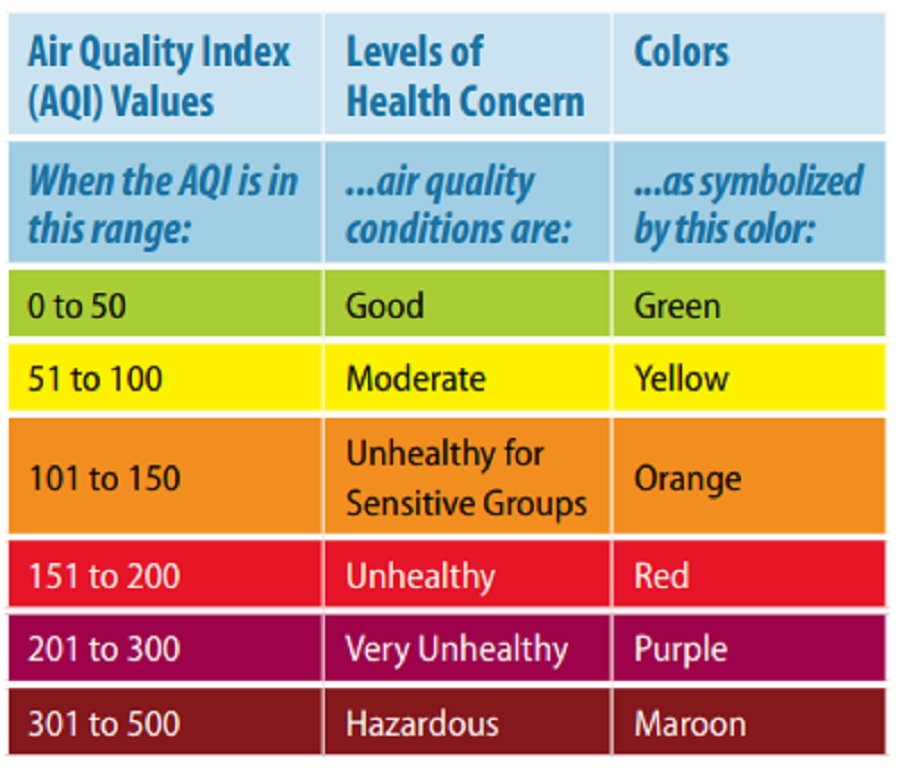

The Hawaii State Department of Health and the National Park Service also track volcanic pollutants through various sensors on the island of Hawaii. Careful attention is paid to sulfur dioxide and particulate matter of size 2.5 µm or less. Beyond obscuring visibility, these volcanic pollutants can also create conditions harmful to life.

According to the Hawaii Department of Health, individuals with pre-existing respiratory conditions are the primary group at risk of experiencing health effects from vog exposures, but healthy people may also experience symptoms.

The Hawaii Department of Health adds that sulfur dioxide alone can be harmful to people. Physically-active asthmatics are most likely to experience serious health effects, with even short-term exposures causing bronchoconstriction (narrowing of the airways), which in turn creates asthma symptoms. Potential health effects increase as sulfur dioxide levels and/or breathing rates increase. When “unhealthy” levels are reached, even non-asthmatics may experience breathing difficulties. Other symptoms of sulfur dioxide exposure include eye, nose, throat, and/or skin irritation, coughing and/or phlegm, chest tightness and/or shortness of breath, and increased susceptibility to respiratory ailments. Some people also report fatigue or dizziness when exposed to sulfur dioxide. While even short-term exposure is connected to increased visits to emergency departments and hospital admissions for respiratory illnesses, long-term health effects of prolonged exposure to volcanic gases are still being studied.

While it’s likely that an eruption near Kilauea’s summit would produce explosion and lava risks and threats inside the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park territory there, gas emissions would spread around the Big Island of Hawaii and perhaps blow to other nearby islands of Maui and Oahu too.

Beyond negatively impacting human health, vog can also negatively impact agriculture directly and humans indirectly. Rain falling through acidic vog can become acid rain which can harm or kill plants and trees, contaminate household water supplies by leaching metals from building and plumbing materials in rooftop rainwater-catchment systems, and harm surfaces exposed to the elements, such as the paint on cars. USGS reports past eruptions have harmed livestock on Hawaii, while even degrading the metal fences that keep livestock contained on the ranches they graze.

On a bigger scale, a new eruption of Kilauea may also be able to alter the weather on the island. Kevin Kodama, Senior Service Hydrologist at the National Weather Service’s Honolulu office, described the impact vog has on the weather.

“Volcanic emissions will tend to hinder rainfall, due to the cloud microphysics and properties,” said Kodama. Too many volcanic aerosols in the air can inhibit the process by which moisture clings to nuclei in the atmosphere to create what eventually becomes rain drops and snow flakes. When Kilauea is active, it makes the ability to produce clouds and precipitation less efficient in areas influenced by those volcanic gasses.

Hawaii is under the influence of a weather pattern tied to El Nino, in which the atmospheric pattern creates unusually dry conditions over the summer and especially the autumn months there. Worsening drought conditions are drying-out tens of thousands of acres of flammable, invasive wild grasses that cover the islands, setting the stage for danger whenever fire weather conditions arrive.

Should Kilauea erupt and those gas emissions inhibit precipitation over the coming months where rain is usually more plentiful, the drought and resulting fire weather conditions could worsen.

For now, scientists studying Kilauea on Hawaii are watching and waiting to see what the volcano will do next.