The Honolulu office of the National Weather Service has issued the 2020-2021 Hawaiian Islands “Wet Season Outlook”, coming out on the heels of NOAA’s overall winter outlook which was released on Wednesday. Hawaii considers its wet season the months of October through April.

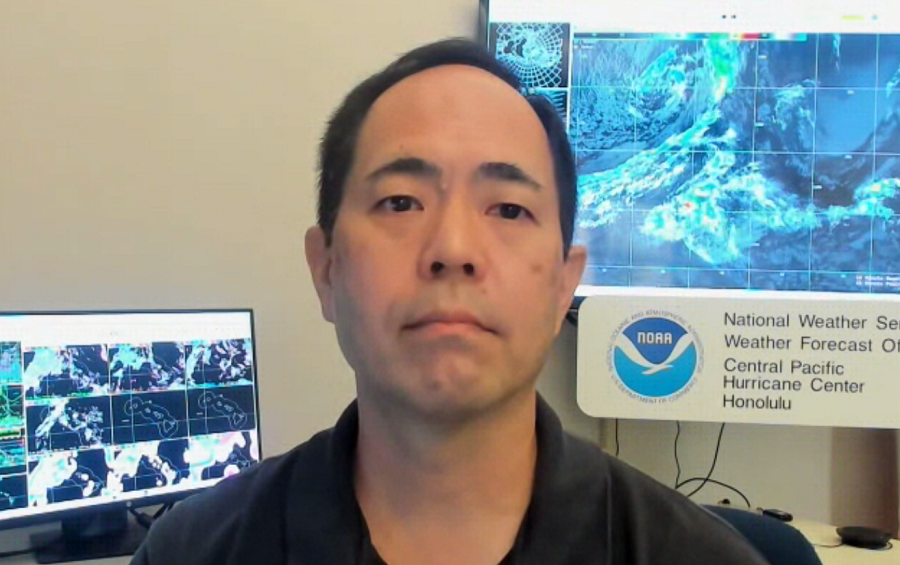

According to Kevin Kodama, Senior Service Hydrologist at the National Weather Service’s Honolulu office, the leeward (south, west) sides of the islands see the most rain during the months of October through April. “The east will see multiple peaks during the year, especially in March, July, and November/December,” Kodama said. However, it’s the period of October to April that the islands see the most rain. As an example, “Honolulu is wettest in December, and driest in the June/July period,” Kodama added.

Driving the forecast for this winter wet season is the presence of La Nina. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center, the current La Nina conditions are likely to continue through to the spring of 2021. Because of that, climate model consensus favors above average rainfall throughout Hawaii’s wet season. According to the National Weather Service, rainfall distribution can be influenced by the strength of La Nina. “Stronger La Nina events can have a higher than normal trade wind frequency which will focus rainfall on windward areas; weaker La Nina events tend to have more weather systems that produce significant leeward rainfall,” the Honolulu office of the National Weather Service wrote in a seasonal forecast update.

La Nina describes anomalous warming of the Pacific Ocean waters near and around the equatorial Pacific; El Nino is the opposite, which describes an anomalously cooling of these waters. When the Pacific anomalously warms or cools, it sets the stage for different types of climate patterns around Hawaii and North America. Usually these large scale climate cycles can help inform meteorologists and climatologists how subsequent weather patterns could unfold in coming months.

“The Pacific is the heat engine of the climate system,” said Amy Clement, a professor of Atmospheric Science at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. The school is located on Virginia Key adjacent to Miami, Florida. “Imagine dropping a pebble in a pond and is sends out ripples,” she says, relating to how what happens in the Pacific can impact global weather patterns. “The pebbles are these giant convective clouds that have all kinds of weather associated with them. They send the ripples throughout the global atmosphere.”

“With La Nina well established and expected to persist through the upcoming 2020 winter season, we anticipate the typical, cooler, wetter North, and warmer, drier South, as the most likely outcome of winter weather that the U.S. will experience this year,” said Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. Kodama says the same phenomena that drives those conditions on North America will translate to a wet wet season in Hawaii.

Based on the assessment of Kodama and the National Weather Service, drought recovery is more likely on the smaller islands of Kauai and Molokai and over the windward slopes of Maui and the Big Island of Hawaii. However, the same phenomena sets the stage for the possibility of drought to continue through the wet season in some areas, especially over the leeward areas of Maui and the island of Hawaii.

Beyond La Nina, another natural event could also influence the wet season forecast. For years, the Kilauea Volcano has erupted lava on the surface of eastern Hawaii Island. In addition to lava, Kilauea also vented a significant amount of volcanic gas that could impact weather. However, since the conclusion of the 2018 Lower East Rift Zone eruption of Kilauea in the fall of that year, there has been no lava and very little volcanic gas coming from Hawaii’s active volcano.

“Volcanic emissions will tend to hinder rainfall, due to the cloud microphysics and properties,” said Kodama. Too many volcanic aerosols in the air can inhibit the process by which moisture clings to nuclei in the atmosphere to create what eventually becomes rain drops and snow flakes. When Kilauea is active, it makes the ability to produce clouds and precipitation less efficient in areas influenced by those volcanic gasses. “With the lack of volcanic emissions, conditions will return to normal or back to a normal type of regular rainfall,” Kodama said. “In the last couple of summers, on the Kona side of the Big Island, they’ve had pretty wet summers. Normally, the summer season is their (Kona area) wet season, but if you look at this past summer, they’ve had a very wet summer.” One particular rain gauge near Kona has indicated that rainfall this summer was nearly double what the normal amount usually is.