The odds of a hurricane forming along or near the U.S. East Coast are improving for next week; while odds continue to grow, it is still not yet definitive. Computer forecast models used by meteorologists to aid with their predictions have offered a variety of possible scenarios in which a tropical cyclone takes shape near the U.S. East Coast. With the National Hurricane Center boosting odds of one disturbance they’re tracking to become a tropical cyclone at 60% now, and this afternoon’s run of the American GFS and European ECMWF forecast models suggesting trouble for the east coast, more attention will be paid to a possible east coast landfall rendezvous.

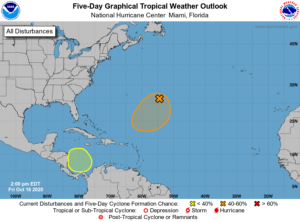

In the latest Tropical Outlook issued by the National Hurricane Center in Miami, Florida a short time ago, they discuss two areas of concern being tracked within the Atlantic Hurricane Basin.

The first area of concern, and the greatest area of concern, is a disturbance located south and east of Bermuda. According to the National Hurricane Center, shower activity associated with a broad non-tropical low pressure system located about 600 miles east-southeast of Bermuda is continuing to become better organized, and satellite wind data indicates that the circulation has become somewhat better defined. They add that additional development of this system is expected, and a subtropical or tropical depression could form during the next few days while the low meanders over the central Atlantic well to the southeast of Bermuda. They say there is a 40% chance of tropical cyclone formation over the next 48 hours and a 60% chance of formation over the next five days.

The second area of concern is over a portion of the Caribbean Sea. The National Hurricane Center says a broad area of low pressure is expected to form early next week over the southwestern Caribbean Sea; some gradual development of this system will be possible through the middle of next week while it moves slowly over the southwestern or western Caribbean Sea. For now, there’s no chance of tropical cyclone formation over the next 48 hours, but those odds grow to 30% over the next 5 days.

Computer forecast guidance has offered different solutions to how these systems form and where they travel with time. Earlier this week, guidance suggested these two systems would come together to form a tropical cyclone near Cuba and head towards Florida.

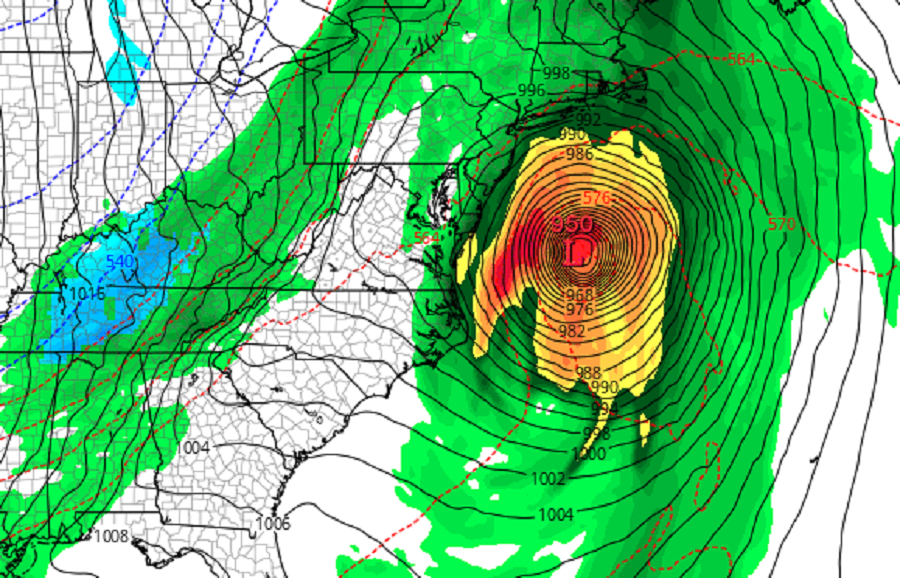

Today, the American GFS forecast model suggests a more ominous outcome. It develops the system near Bermuda but moves it into the North Atlantic, away from the U.S. Coastline. However, it intensifies the system over the Caribbean, bringing it across Cuba into the Bahamas. From there, it intensifies into a potent storm and heads to the northeast coast of the United States, where it would make landfall as a potent 949 mb hurricane.

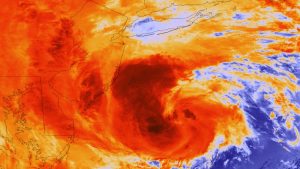

The European ECMWF computer model forecast is different from the American GFS but still produces an ominous result. The ECMWF develops the system near Bermuda and has it circle around the Atlantic before heading north. While it doesn’t develop the Caribbean system the same way the GFS does, it develops an area of low pressure around Florida and brings this up the East Coast as a traditional coastal storm moreso than a tropical cyclone. It too brings wind-whipped rains to a large portion of the coast.

Whether or not the GFS or ECMWF are right are wrong is not yet known. Accuracy of forecast models degrades over time. Because these storms are more than 5 days out from forming, confidence is low in the model output. However, because the model guidance has been fairly consistent run-to-run with developing these storms, confidence for medium range guidance is a little higher than it would be otherwise.

October is no stranger to severe tropical cyclones. In 2018, Hurricane Michael hit Florida as a Category 5 hurricane on October 10. In 2012, Sandy struck the New Jersey Coast as a powerful cyclone in transition from tropical to non-tropical. Even though Sandy wasn’t a hurricane, it was one of the costliest disasters to strike New Jersey and New York, claiming many lives in the process. Sandy struck New Jersey on October 29.

With the traditional list of names exhausted, the National Hurricane Center is using Greek letters to name tropical storms and hurricanes. The next system to earn a name this season will be called Epsilon. After Epsilon would be Zeta followed by Eta. The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was the busiest on record; it produced a Tropical Storm Zeta in December. But a Greek letter beyond Zeta has never been used before; it remains to be seen if Eta or others will be used for the first time in 2020.