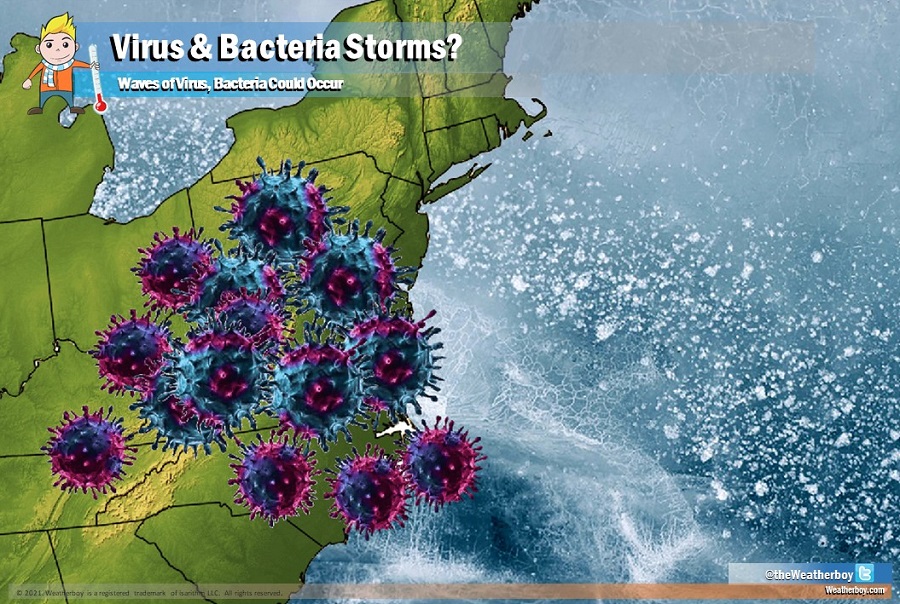

Beyond your typical snow and rain storms, scientists may also be able to predict swarms of viruses and bacteria that storm out potentially harmful matter onto humans, animals, and plants below. A Study published in the ISME Journal, the Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology, dove into the deposition rates of viruses and bacteria above the atmospheric boundary layer to understand how they move about in the air.

Aerosolization is the process or act of converting some type of substance into small particles that can be small and light enough to be carried through the air. Aerosols occur naturally in the environment: dust from land and salt from oceans can break up into tiny particles and travel in the air. Disease agents, like infectious virus or bacteria, can also be aerosolized when someone infected coughs, sneezes, exhales, or vomits. Aerosolization also occurs through various everyday processes like a flushing toilet.

Scientists now believe that the aerosolization of viruses and bacteria can extend well beyond a person’s cough or sneeze. In the study authored by Isabel Reche, Gaetano D’Orta, Natalie Mladenov, Danielle Winget, and Curtis Suttle, they cite “we demonstrate that even in pristine environments, above the atmospheric boundary layer, the downward flux of viruses ranged from 0.26 x 109 to >7 × 109 m−2 per day.” The deposition rates of bacteria, though, were in some cases more than 400x greater, which their analysis showed a range of 0.3 × 107 to >8 × 107 m−2 per day. The deposition rates for viruses were associated with atmospheric transport from marine environments more so than other terrestrial sources, while rain storms and Saharan dust intrusions appeared to increase the deposition of bacteria.

Viruses and bacteria also could stay viable in the air for different times. According to the study abstract, “Virus deposition rates were positively correlated with organic aerosols <0.7 μm, whereas, bacteria were primarily associated with organic aerosols >0.7 μm, implying that viruses could have longer residence times in the atmosphere and, consequently, will be dispersed further.”

In these situations, viruses and bacteria simply didn’t float around in the air on their own. The study showed that viruses and bacteria attached themselves to other particles floating in the air, such as dust from soil or marine organic aggregates. The full journal article can be seen here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41396-017-0042-4

Viruses are the most abundant microbes on the planet. Scientists believe there are more than 100 million different kinds of viruses around the Earth; they also estimate there are 1030 virus particles in the ocean alone. Not all viruses are lethal; some can be manipulated to be beneficial to human health. Scientists are exploring ways to cure cancer, correct genetic disorders, and fight pathogenic viral infections. But every now and then, an especially lethal virus appears on the world stage, as is the case with the current ongoing pandemic.

By understanding how viruses and bacteria travel and spread in the atmosphere, scientists can develop forecasts areas where there could be a significant “downpour” of harmful viruses or bacteria. In these cases, people could take preventative measures to protect themselves and their plants and animals from matter that could be hazardous without additional precautionary measures. While this science is in its infancy today, future weather forecasts may also alert you to the presence of large quantities of a hazardous virus and bacteria count in the air much like pollen and pollution forecasts are made today.