With the northeast being slammed by its third nor’easter today in less than 2 weeks, many are wondering if Old Man Winter has more surprises up his sleeves. If one is to believe computer model forecast output, the answer is a solid “yes.” And unfortunately for storm-weary residents of the eastern United States, it’s becoming more likely that at least two more potent coastal storms will impact the eastern United States before March wraps up, bringing wind-whipped snow, coastal flooding, and the threat of wind damage to an area that has seen plenty of all of those hazards over the last few weeks. It is also more likely that the area of heavy snow will broaden and shift south from today’s impact zone, perhaps bringing snow to places in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware that have seen little snow this season. Washington, DC, Baltimore, MD, and Philadelphia, PA could see significant snow even as the calendar pushes forward closer to spring every day.

The reason for the pile-on of winter storms in the east has to do with an evolving atmospheric weather pattern. We’re recovering from a period of anomalous warm air in the stratosphere, known as a “sudden stratospheric warming event.” The slow downward propagation of anomalous warm air from the higher stratosphere to the lower troposphere is leading to a negative North Atlantic Oscillation. The North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) is a weather phenomenon in the North Atlantic Ocean of fluctuations in the difference of atmospheric pressure at sea level between Iceland and the Azores. A permanent low-pressure system over Iceland (the Icelandic Low) and a permanent high-pressure system over the Azores (the Azores High) control the direction and strength of westerly winds into Europe. The relative strengths and positions of these systems vary from year to year and this variation is known as the NAO. A large difference in the pressure at the two stations (a high index year, denoted NAO+) leads to increased westerlies and, consequently, cool summers and mild and wet winters in Central Europe and its Atlantic coastline. In contrast, if the index is low (NAO-), westerlies are suppressed, northern European areas suffer cold dry winters and storms track southwards toward the Mediterranean Sea. This brings increased storm activity and rainfall to southern Europe and North Africa. Beyond impacts to Europe, the positive or negative NAO can also lead to impacts to the eastern United States. A blocking high usually sets-up in the eastern Atlantic when the NAO is negative, forcing storms that cross the country to curve up the US east coast. Depending on the strength of that blocking pattern, storms can slow down, intensify, and/or bring down cold air from northern latitudes into the Eastern United States.

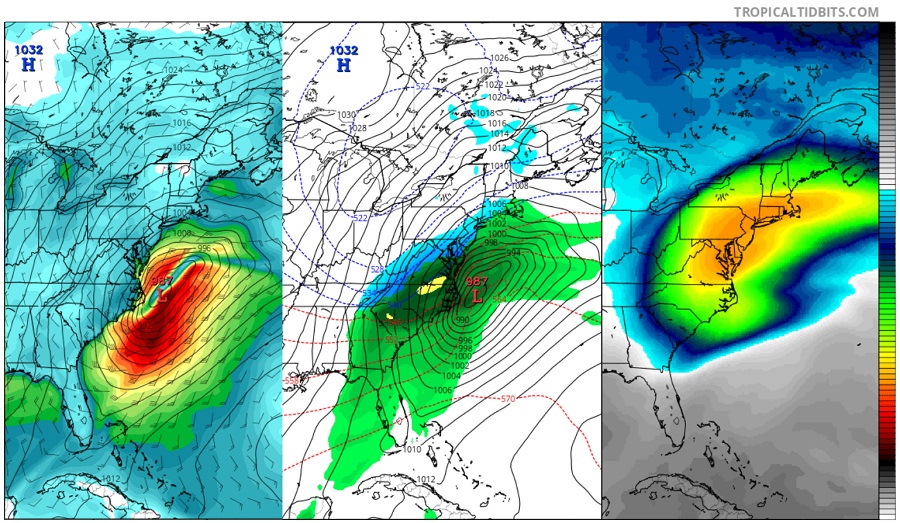

With an active pipeline of storms coming in from the western and central states with the NAO continuing to go negative, conditions are ripe for coastal storms along the US east coast. Different parts of the east coast have been impacted differently this winter due to storm path and storm strength. Some paths have been close to the coast, bringing milder temperatures and rain or a rain-snow mix far north. Other storms have intensified rapidly, “bombing out” through a phase of bombocyclogenesis; this process has produced heavy thundersnow for some. With an evolving storm track and weather pattern over both eastern North America and the western Atlantic Ocean, wintry weather may impact locations further south into the Mid Atlantic than earlier storms. The area of wintry weather may also expand in coverage with storms being able to deepen and intensify before entering the waters off the coast of New England. These factors are increasing meteorologists’ confidence that forecast models are onto something: that more coastal winter storms will indeed impact the east coast.

While today’s blizzard in southeastern New England slowly clears out over the next 48 hours, eyes will be on the next weather maker. Fortunately for those recovering from this barrage of storms, the next storm system may not strike until the early part of next week, giving people a chance to catch their breath before the next system arrives.