One of the most popular and famous beaches in the United States, if not the world, is disappearing: Kaanapali Beach on the Hawaiian Island of Maui has been facing unprecedented beach erosion this year. While local officials and property owners are scrambling on short-term plans, some are calling for the relocation of this resort community, which includes mega resort hotel complexes, away from the coast.

According to the Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands within the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) for the State of Hawaii, Kaanapali Beach has been negatively impacted by chronic erosion and extreme seasonal erosion over the previous four decades. They warn that sand loss from the natural beach systems, or littoral cells, is expected to continue and likely accelerate over time.

The first master-planned resort in the State of Hawaii, Kaanapali was developed by American Factors, Inc. beginning in 1959. Located a couple miles north of the old whaling community of Lahaina, the one-mile stretch of beachfront property opened as the Kaanapali Resort in 1962.

Major resort hotels now on Kaanapali Beach (in order from the south end closest to Lahaina to the north end) are the Hyatt Regency Maui (opened in 1980), Maui Marriott (opened 1982 but has since turned into Marriott’s Maui Ocean Club), Westin Maui Resort & Spa (originally opened as the Maui Surf in 1971, then rebuilt as the Westin 1987), Kaanapali Beach Hotel (1964), Sheraton Maui Resort & Spa (1963 but completely rebuilt in 1996), Royal Lahaina (1962), and Maui Kaanapali Villas (originally a Hilton when it opened in 1963 and sometime referred to as Hale Kaanapali. In addition to hotels, there are also luxury condominium towers, including the Alii, located between the Marriott and Westin properties, and The Whaler. The Whaler is next to Whalers Village shopping center, a popular beachfront commercial property with restaurants and stores.

When Kaanapali Beach first opened in the 1960s, a wide sandy beach existed in front of the resort properties. But in recent years, especially this year, all of these properties became uncomfortably closer to the ocean, with the Alli condo complex now closest to the water’s edge.

View this post on Instagram

The resort community featured a concrete sidewalk lined with lush landscaping, coconut palm trees, and other tropical foliage that strolled the beach resort from one end to the other, connecting the resort complexes to each other and the Whalers Village shopping area. The popular pedestrian walkway also provided access to the beach, with paths cut into the greenery above the sandy beach leading to the warm surf and nearby beach showers.

After a significant swell event in late September and early October, the beachwalk had “KEEP OFF” signs and detour arrows up as chunks of it collapsed into the adjacent surf. Wide sandy beaches once covered with sunbathers went under water at high tide while the tropical foliage that once lined the sidewalk is submerged or washed away into the ocean. With tropical foliage and the concrete sidewalk being eaten away by the angry surf, the ocean is getting perilously closer to the hotel and condo towers that line the resort.

But the erosion isn’t consistent. In the time since the most severe erosion occured earlier this autumn, surf has returned a large part of the beach, bringing sand in front of places like the Alii complex where little existed just months ago. But while sand shifts for the better there, sand continues to shift away from the south end of the resort, where the ocean is eating into the Hyatt resort’s beachfront.

For now, the state has approved a temporary erosion skirt fronting the Hyatt property on the south-end of the Kaanapali Beach. But other mid-range and long-range solutions are still being discussed.

DLNR says that the beach may be conserved with sand nourishment or managed retreat or a combination of approaches, but managed retreat is a long-term action that does not address chronic beach loss happing now. “Managed retreat is a multidecadal process, requiring years of planning, funding, and implementation,” DNLR cautions in a report about the erosion at Kaanapali. They add that as a synergistic mid-term step in a much longer adaptation process, the beach can be “restored through sand nourishment utilizing sound engineering design and best practices to ensure protection of the nearshore marine environment.”

Sand naturally shifts around at the beach, being driven randomly by ocean currents, storms, and seasonal changes with the weather and weather patterns. Erosion has been documented at Kaanapali even before the resort was built in the 1960s and varying degrees of erosion and changes in the location of the shoreline have occurred every year since. However, this year’s erosion was the most significant yet.

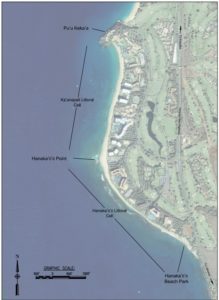

To combat the erosion in the short time, the State of Hawaii is co-sponsoring an endeavor with the Kaanapali Operators Association to restore roughly 7,500 feet of beach. Approximately 50,000 cubic yards of sand would build the beach wider between Hanakaʻōʻō Beach Park and Hanakaʻōʻō Point, and nearly 25,000 cubic yards of sand would be placed on the dry beach between Hanakaʻōʻō Point and Puʻu Kekaʻa. By depositing sands in these areas, it is assumed Mother Nature will help distribute the sand across Kaanapali Beach to protect this tourist attraction and the buildings and businesses that line it.

DNLR says, “A healthy beach attracts visitors that can boost local economies by increasing demand for local employees, recreational activities on the beach, property values, and retail sales. ”

While some are balking at the estimated $12 million short-term beach restoration effort, officials are also quick to point out that Kaanapali Beach Resort generates $150 million in tax revenue each year, not to mention the impacts to the island’s economy and the 5,000 members of the workforce there. Local residents have also used public meetings held by the state on the beach restoration projects to not only voice their concerns about the pricetag, but the environmental impact too. Some believe artificially bringing sand back to the beach could harm marine life, interfering with nearby reef fish that some depend on for food.

However, DNLR is quick to point out that this beach restoration effort doesn’t fix the long-term problem: erosion will continue and in as little as a decade from the time of the completion of the beach restoration project, Kaanapali Beach will be right back to where it started to today. Due to that, managed retreat needs to be seriously considered.

But what managed retreat means and who bears the cost of that remains unknown. Dismantling existing resorts and rebuilding them away from the ocean’s edge would likely cost an astronomical figure. And while the coastal resorts are the primary economic engine for the island, it remains to be seen what the property owners’ and tax payers’ appetite are for bearing the cost of such a move –or what the appetite is for there to be any move at all.

One thing is certain: sands will continue to shift on Kaanapali and sooner or later the ocean will claim or reclaim land it touches on Maui and elsewhere around the world.