After going through what seemed like a period of relentless winter storm activity in which storm after storm dropped accumulating snow in the northeast, snow and ice accumulations to the Gulf Coast, and blizzard conditions to the west, it appears Old Man Winter will be taking a break to thaw out a bit for the next week or two. But beyond that, will snowstorms return? After all, March has featured some of the largest blizzards of the year.

While the days are getting longer and the calendar inches closer to spring and summer, the month of March has had a history of creating several notable snowstorms. According to the National Weather Service, two of the top three most impactful snowstorms to ever strike the United States since the 1950s were March storms. And perhaps the most famous March storm is the Blizzard of 1888, which brought very heavy snow to the northeast after a stretch of very mild weather. In recent times, the March “Superstorm” of 1993 was the most noteworthy, dropping heavy snow across a large part of the Eastern United States. But many storms have impacted the region over the years. But even outside of those two historic storms, there have been many impacts in March from Old Man Winter.

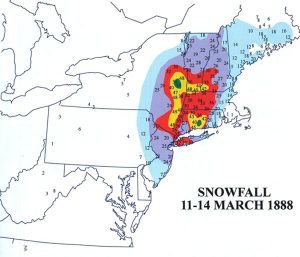

The most dramatic March weather occurred in March, 1888. Unseasonably mild temperatures surged up the east coast, leading many to think Spring was about to arrive. However, they couldn’t be more wrong. In places like New York City, the unseasonably mild air was joined by soaking rains. On the night of March 12, the rapidly intensifying storm brought cold air into the Mid Atlantic, quickly changing the mild rain to a cold, heavy snow. The National Weather Service estimates that this nor’easter dropped as much as 50″ of snow in parts of Connecticut and Massachusetts, while parts of New Jersey and New York had up to 40″. Northern New England didn’t escape the wrath of this coastal storm either; places like northern Vermont saw around 20″ of snow. The heavy snow was whipped by fierce winds, creating unimaginably huge snow drifts. Drifts were reported to average 30-40 feet, over the tops of homes from New York City to New England; there were also reports that some 3-story homes in New England were covered by snow drifts. The extensive drifting was created by severe winds; 80mph gusts were reported in New England while New York City officially recorded 40mph winds. Despite the mild weather ahead of the storm, temperatures nosedived in the storm’s wake; New York City’s Central Park Observatory reported a minimum temperature of 6 degrees and a daytime average of 9 degrees on March 13, making it the coldest readings ever for the month at that time.

The Blizzard of 1888 paralyzed the region for days. Huge snow drifts crippled the normally busy New York – New Haven rail line for 8 days. The transportation gridlock as a result of the storm was partially responsible for the creation of the first underground subway system in the US, which opened nine years later in Boston. Communication was also hampered; the telegraph infrastructure was impacted, isolating Montreal and most large northeastern cities from Washington, DC to Boston for days. After the storm, New York began placing its telegraph and telephone cables underground to prevent future storm damage. From the Chesapeake Bay north east through New England, more than 200 ships were either grounded or wrecked, claiming more than 100 lives at sea. More than 400 people died from the storm on land, with half of the deaths from New York City alone. In today’s dollars, the storm created about $680million in damages.

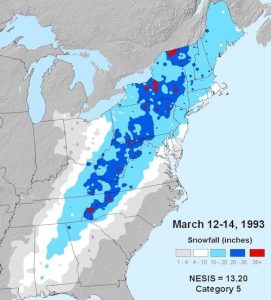

The March Superstorm of 1993 was another March snowstorm of historic proportions. Also known as the “Storm of the Century” and the “Great Blizzard of 1993″, the enormous storm moved through the Gulf of Mexico and through the eastern United States and Canada, dumping heavy snow along the way. Heavy snow was first reported in highland areas as far south as Alabama and northern Georgia, with Union County, Georgia reporting up to 35 inches of snow in the north Georgia mountains. Birmingham, Alabama, not known for its snow, especially in March, measured 13″. The Sunshine State wasn’t left out either; the Florida panhandle reported 4″ of snow from the storm. Severe weather broke out on the south side of the storm, creating tornadoes that claimed dozens of lives. Damaging winds in the storm knocked out power to more than 10 million households, keeping many in the dark for days. The death toll of the storm reached 208.

The March Superstorm first hit on March 12 and didn’t exit the US until March 14. The amount of snow that fell over that stretch of time was immense in both volume and area. Portions of the Appalachian Mountain region saw 5 feet of snow while some snowdrifts were as high as 35 feet. Mount Leconte, Tennessee recorded 60 inches of snow while Mount Mitchell in North Carolina recorded 49”. The volume of the storm’s total snowfall was later computed to be 12.91 cubic miles.

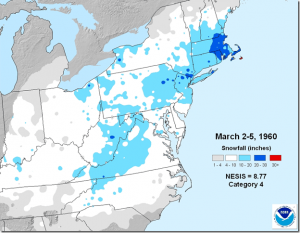

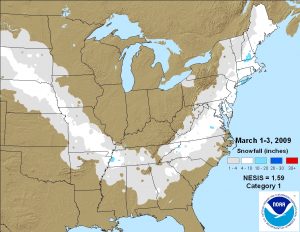

Over the years, many other major snowstorms have struck in March. Here’s a sample of some snowfall maps from those storms:

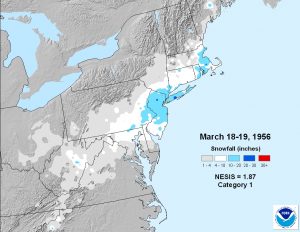

The 1956 storm’s heaviest snowfall area was over the northern half of New Jersey, the New York City metro area, and Long Island. Places just outside of New York City and Boston reported more than 20″ of snow from this 2-day event. Similar to the 2021 winter storm weather pattern, the rain/snow line from this system moved up the DelMarVa Peninsula into southern Delaware, keeping snow totals lighter for Baltimore and producing no accumulating snow near Ocean City, Maryland.

The March 1960 storm brought very significant, widespread snow to a large part of the Northeast and Mid Atlantic. While the heaviest snow from this storm struck eastern Massachusetts, where 20-30″ of snow fell, this storm dropped significant, plowable snow across much of North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and every state north and east from there. More than 10″ fell across western Virginia and eastern West Virginia, with high terrain in the Appalachian Mountains reporting more than 20″ too. Unlike other storms that brought a rain/snow line far up the Mid Atlantic coast, this storm had plenty of cold air to work with, helping keep the rain/snow line closer to the North and South Carolina border.

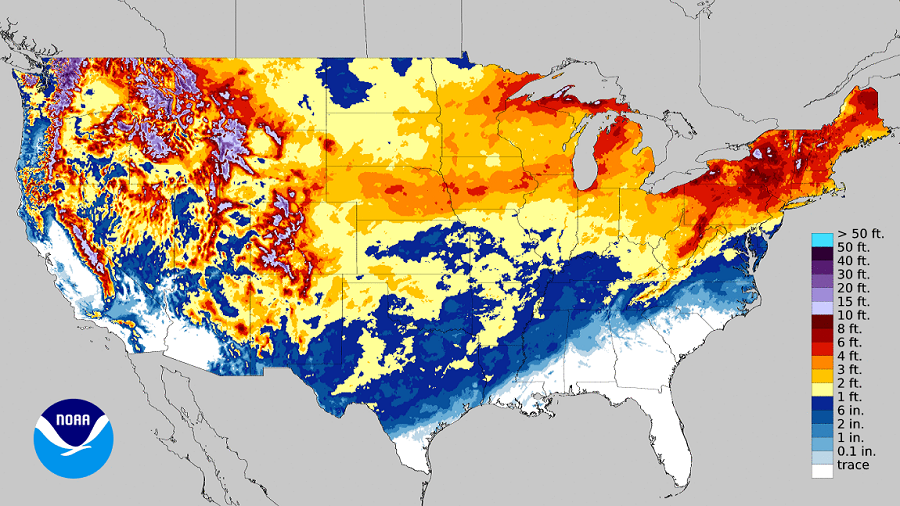

A multi-day storm during the first days of March 2009 brought significant snow across a large part of the eastern United States. Strong, cold high pressure locked in over the Great Lakes kept places like Michigan dry, but it also helped steer a storm diving out of the central Plains to approach the central Gulf states and head north along the U.S. East Coast. After dropping significant snow over Nebraska and Missouri, the storm produced accumulating snow across northern Mississippi, much of Alabama, and northern Georgia. From there, the area of snow spread north, bringing accumulations to northern South Carolina and North Carolina before dumping heavier snow across Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, and much of eastern New England. While a pocket of heavy snow fell over eastern Tennessee, some of the heaviest totals came in from Long Island, New York and southern New Hampshire.

There are currently no large scale snowstorms on the horizon in the immediate future. But will that change?

While meteorologists have many tools at their disposal to create weather forecasts, two primary global forecast models they do use are the ECMWF from Europe and the GFS from the United States. While the models share a lot of the same initial data, they differ with how they digest that data and compute possible outcomes. One is better than the other in some scenarios, while the opposite is true in others. No model is “right” all the time. Both of these global models depict surface conditions well into the future. The American GFS forecast model suggests the country will be free of widespread significant snowstorms for the next 10 days while the European ECMWF suggests the same for only the next 7 days. Beyond that, the European model hints at a winter storm in the northeastern United States.

However, it is likely this model output will change in the coming days in both of these global systems as new observations are made and new data is ingested by the computers to refine its forecasts. As an example, just days ago, some model output suggested a snowstorm could impact the Mid Atlantic at the end of this week. That is no longer the case.

Winter storms thrive on the energy released when two very different air masses clash together. As conditions warm to the south with the longer March days while there’s still plenty of cold air to the north lingering from the winter and the snowpack it left behind to date, the ingredients are there for interesting storm possibilities. We’ll just have to wait and see if March 2021 will have its own blizzard too.