It’s been seismically active in the eastern half of the United States in recent days, with two earthquakes hitting New York, one in Ohio, one in Arkansas, and two in Tennessee. Even Canada got into the action, with an earthquake hitting in Ontario province north and west over the border from New York state’s latest quake. A large population has been rattled by these quakes, with hundreds of reports coming into USGS from people feeling shaking in Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Ohio, New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

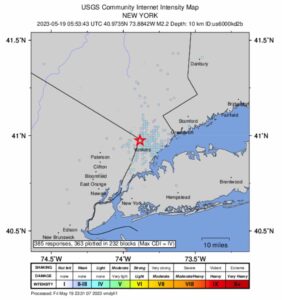

The first of the recent earthquakes struck just north of New York City on Friday morning. Hundreds of people used the USGS website and their “Did you feel it?” web reporting tool to report shaking they felt the early morning earthquake that struck the Hastings-on-Hudson area of New York, just outside of New York City and across the Hudson River from New Jersey. The relatively weak magnitude 2.2 event struck at 1:53 am this morning in Westchester County at a depth of 9.8 km. While there were no reports of damage, people used both social media and the USGS website to share their experiences. People across New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut reported feeling the late-night earthquake.

According to USGS, earthquakes with a magnitude of 2.0 or less are rarely felt or heard by people, but once they exceed 2.0, as this event did, more and more people can feel them. While damage is possible with magnitude 3.0 events or greater, significant damage and casualties usually don’t occur until the magnitude of a seismic event rises to a 5.5 or greater rated event.

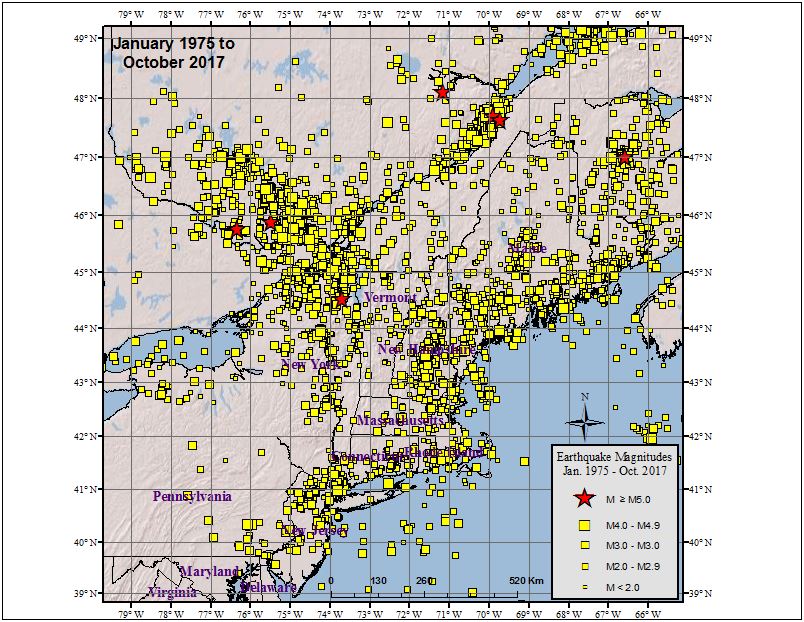

Within the last 30 days of this particular earthquake, USGS reported no other earthquakes around the area of that New York City metro area quake. Last month, there were several earthquakes in western New York near Watertown. In April, an earthquake also rocked portions of southern New Hampshire.

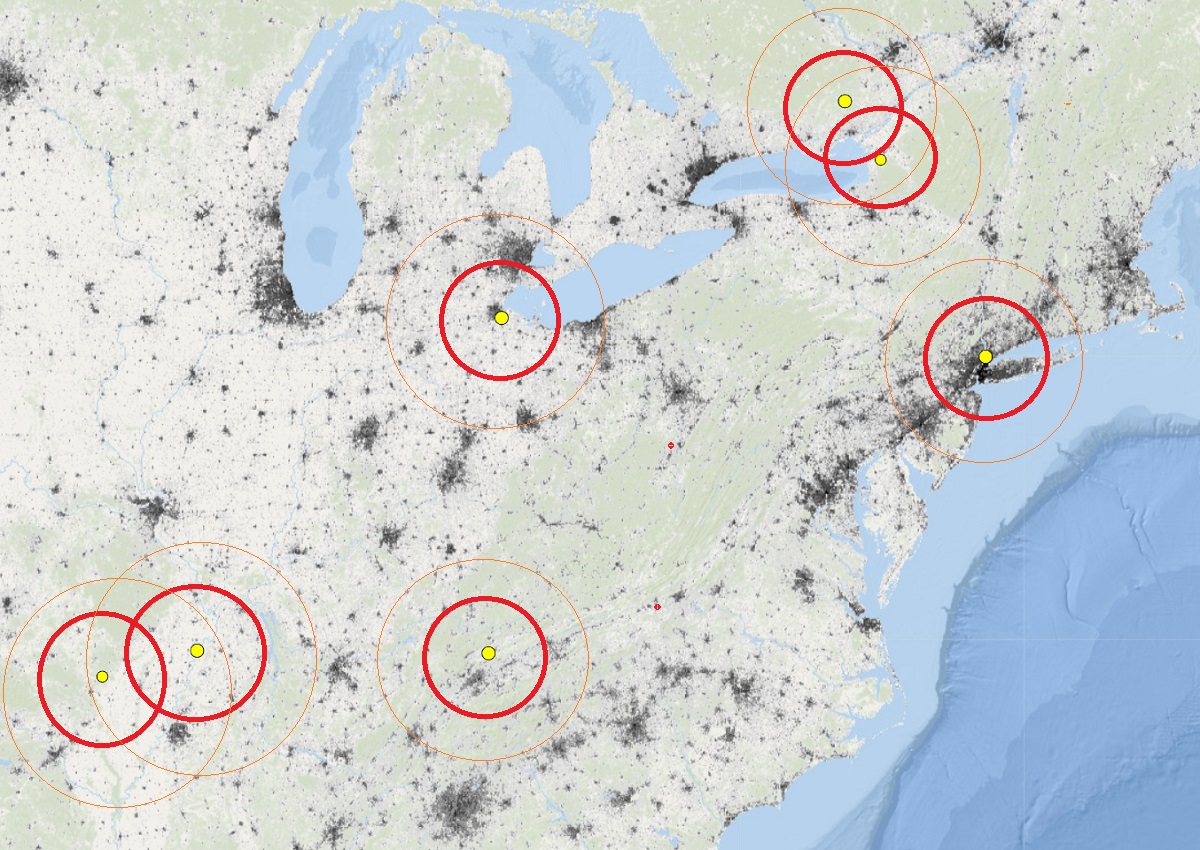

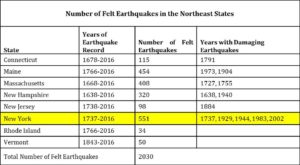

According to the Northeast States Emergency Consortium (NESEC), New York is a state with a very long history of earthquake activity that has touched all parts of the state. Since the first earthquake that was recorded in December 19, 1737, New York has had over 550 earthquakes centered within its state boundaries through 2016. It also has experienced strong ground shaking from earthquakes centered in nearby U.S. states and Canadian provinces. Most of the quakes in New York have taken place in the greater New York City area, in the Adirondack Mountains region, and in the western part of the state.

While many of the earthquakes to hit New York are weak like Friday’s, some have been damaging. Of the 551 earthquakes recorded between 1737 and 2016, 5 were considered “damaging”: 1737, 1929, 1944, 1983, and 2002.

While most of New York’s earthquakes have been in the Upstate, New York City has also seen damaging earthquakes over the years. At about 10:30 pm on December 18, 1737, an earthquake with an unknown epicenter hit New York with an estimated magnitude of 5.2. That quake damaged some chimneys in the city. On August 10, 1884, another 5.2 earthquake struck; this quake cracked chimneys and plaster, broke windows, and objects were thrown from shelves throughout not only New York City, but surrounding towns in New York and New Jersey too. The shaking from the 1884 earthquake was felt as far west as Toledo, Ohio and as far east as Penobscot Bay, Maine. It was also reported felt by some in Baltimore, Maryland.

Not long after the New York City-area earthquake, a fresh earthquake hit western upstate New York Friday evening followed by another somewhat stronger earthquake just northeast above the U.S. / Canada border in Ontario on Sunday. Unlike the first earthquake north of New York City that generated hundreds of reports to the USGS website and their “Did you feel it?” reporting tool, these two recent earthquakes were barely felt and caused no damage nor injuries. The 10:57 pm Friday night event was a magnitude 1.6 earthquake; it hit Rodman near Watertown, New York. USGS also reported the one that hit the Ontario province of Canada on Saturday morning at 7:36 am. This magnitude 2.1 event struck south and west of Perth, north and west of the most recent New York state earthquake.

While earthquakes around New York are common, the same isn’t true for Ohio. Nevertheless, an earthquake struck there on Friday evening too. According to USGS, a magnitude 2.6 earthquake struck outside of Toledo in northwestern Ohio at 8:17 pm. The Friday evening earthquake generated dozens of reports to USGS’s website and the “Did you feel it?” reporting tool they feature on it. Shaking was felt throughout the Toledo area as well as Perrysburg and Bowling Green, Ohio. The earthquake struck just south of Metcalf Field near Lake Township Hall from a depth of only 6.5 km. USGS says this is the first earthquake to strike within a radius of 250 km in the last three weeks.

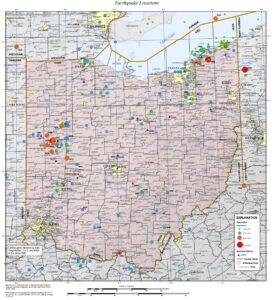

According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Ohio has deployed a seismic network with 21 seismograph stations throughout the state that continuously monitor and record earthquake activity. The Ohio Seismic Network (OhioSeis) went online in January 1999, ending a five-year gap during which there was only one operating station in Ohio. Ohio has 24/7 monitoring and coverage by seismic stations with automatic detection, location and magnitude determination.

Earthquake activity in Ohio is not common. The last earthquake hit on March 20 about 14 miles southwest of Gallipolis; it was a magnitude 2.3 event. On February 4, an even weaker magnitude 2.0 event struck near Athens. On January 23, an earthquake of the same magnitude, 2.0, struck near Fairport Harbor.

USGS says Ohio has experienced more than 160 felt earthquakes since 1776. Most of these events caused no damage or injuries. However, 15 Ohio earthquakes resulted in property damage and some minor injuries. The largest historic earthquake in the state occurred in 1937. The 1936 event had an estimated magnitude of 5.4 and caused considerable damage in the town of Anna and in several other western Ohio communities.

USGS reported two relatively weak earthquakes struck Tennessee in the last few days. The first struck western Tennessee near the Mississippi River at 1:23 am; the magnitude 2.3 event had a depth of 7.4 km. The second hit north and east of Knoxville in the central part of the state on Saturday afternoon; the magnitude 2.8 event hit near New Tazewell at 5:55 pm from a depth of 17.3 km.

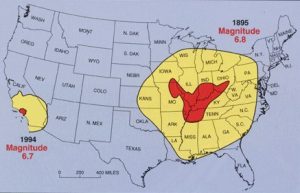

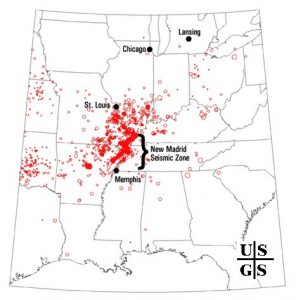

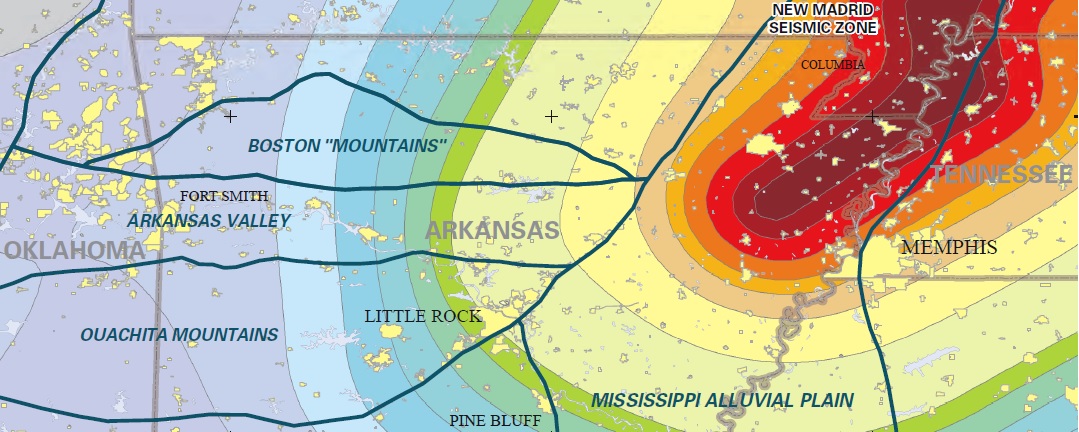

Western Tennessee is located within the New Madrid Seismic Zone, an area famous for a catastrophic series of earthquakes in 1811-1812 that were centered near New Madrid County, Missouri. The New Madrid Seismic Zone is also known as NMSZ for short. The NMSZ extends 120 miles south from Charleston, Missouri, following Interstate 55 to near Marked Tree, Arkansas. The NMSZ consists of a series of large, ancient faults that are buried beneath thick, soft sediments. These faults cross five state lines, the Mississippi River in three places, and the Ohio River in two places.

According to the Missouri Department of Public Safety, the New Madrid Seismic Zone is active and averages about 200 measured events per year (magnitude 1.0 or greater). Tremors large enough to be felt (magnitude 2.5 – 3.0) occur annually. On average every 18 months, the fault releases a shock of magnitude 4.0 or greater, which is capable of local minor damage. A magnitude 5.0 or greater occurs about once per decade, can cause significant damage and be felt in several states.

Earthquakes like the one that occurred Saturday in the central part of Tennessee are unlikely associated with the New Madrid Seismic Zone. However, while USGS says western Tennessee has a higher frequency of damaging earthquake shaking, the risk isn’t that low in central and eastern Tennessee. In the area of today’s earthquake, USGS says its likely this area would see 50-100 damaging earthquakes over 10,000 years. While this number is low, it is much higher than it is elsewhere in the eastern half of the United States, where it’s likely to have 10 or less earthquakes over the same period.

While recent earthquakes in the NMSZ haven’t been very strong nor created any damage, the same wasn’t true for a series of earthquakes that struck during the winter of 1811-1812.

While the US West Coast is well known for its seismic faults and potent quakes, many aren’t aware that one of the largest quakes to strike the country actually occurred near the Mississippi River. On December 16, 1811, at roughly 2:15am, a powerful 8.1 quake rocked northeast Arkansas in what is now known as the New Madrid Seismic Zone. The earthquake was felt over much of the eastern United States, shaking people out of bed in places like New York City, Washington, DC, and Charleston, SC. The ground shook for an unbelievably long 1-3 minutes in areas hit hard by the quake, such as Nashville, TN and Louisville, KY. Ground movements were so violent near the epicenter that liquefaction of the ground was observed, with dirt and water thrown into the air by tens of feet. President James Madison and his wife Dolly felt the quake in the White House while church bells rang in Boston due to the shaking there.

But the quakes didn’t end there. From December 16, 1811 through to March of 1812, there were over 2,000 earthquakes reported in the central Midwest with 6,000-10,000 earthquakes located in the “Bootheel” of Missouri where the New Madid Seismic Zone is centered.

The second principal shock, a magnitude 7.8, occurred in Missouri weeks later on January 23, 1812, and the third, a 8.8, struck on February 7, 1812, along the Reelfoot fault in Missouri and Tennessee.

The main earthquakes and the intense aftershocks created significant damage and some loss of life, although lack of scientific tools and news gathering of that era weren’t able to capture the full magnitude of what had actually happened. Beyond shaking, the quakes also were responsible for triggering unusual natural phenomena in the area: earthquake lights, seismically heated water, and earthquake smog.

Residents in the Mississippi Valley reported they saw lights flashing from the ground. Scientists believe this phenomena was “seismoluminescence”; this light is generated when quartz crystals in the ground are squeezed. The “earthquake lights” were triggered during the primary quakes and strong aftershocks.

Water thrown up into the air from the ground, or the nearby Mississippi River, was also unusually warm. Scientists speculate that intense shaking and the resulting friction led to the water to heat, similar to the way a microwave oven stimulates molecules to shake and generate heat. Other scientists believe as the quartz crystals were squeezed, the light they emit also helped warm the water.

During the strong quakes, the skies turned so dark that residents claimed lit lamps didn’t help illuminate the area; they also said the air smelled bad and was hard to breathe. Scientists speculate this “earthquake smog” was caused by dust particles rising up from the surface, combining with the eruption of warm water molecules into the cold winter air. The result was a steamy, dusty cloud that cloaked the areas dealing with the quake.

The February 1812 earthquake was so intense that boaters on the Mississippi River reported that the flow of the water there reversed for several hours.

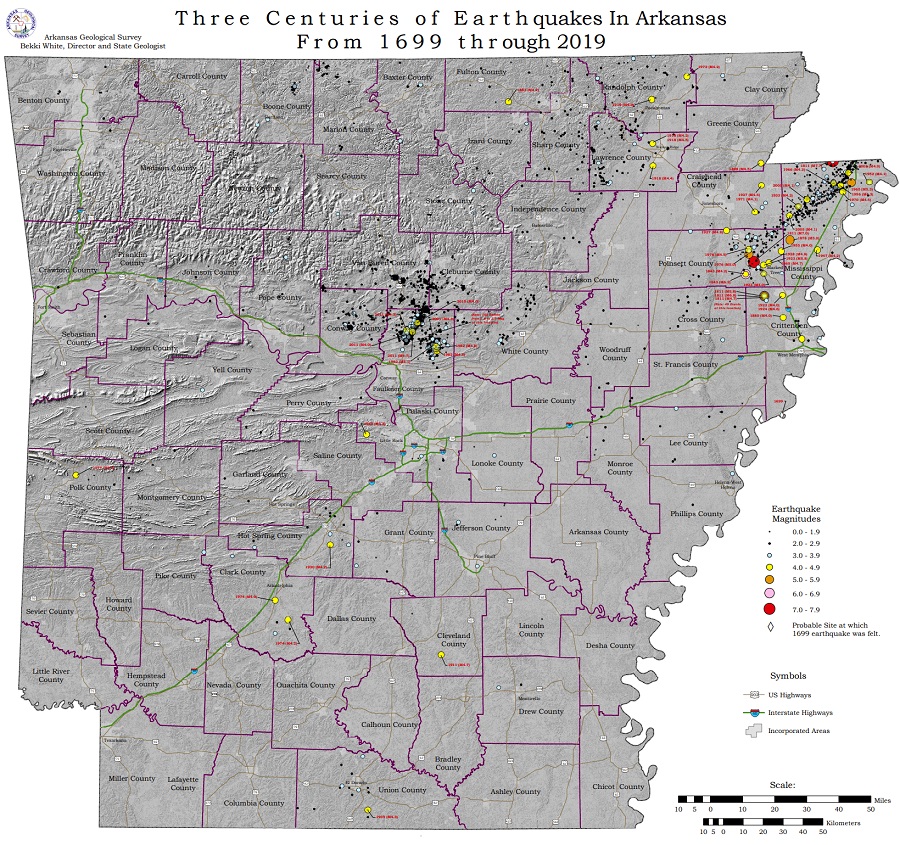

Arkansas also got in on the earthquake action in recent days. A very weak magnitude 1.6 event struck between Batesville and Jonesboro in the north-central part of the state on Thursday morning at 6:11 am; it had a depth of 7.2 km. Like the Tennessee quake, the Arkansas one wasn’t far from the NMSZ either.

While Thursday’s earthquake was relatively inconsequential, authorities are concerned that people aren’t properly prepared for when a big earthquake will strike this region. The matter of a larger destructive earthquake in this area is more of a matter of “when” rather than “if.”

Arkansas isn’t a stranger to earthquakes. According to the Arkansas Geological Survey, hundreds of earthquakes have been reported throughout the state over the last several hundred years, with records going as far back as 1699. While many are centered near the heart of the NMSZ closer to the Tennessee/Missouri border, there are also pockets of seismic activity near today’s earthquake across Sharp, Lawrence, and Randolph Counties as well as across the middle of the state north of Little Rock.

The area remains seismically active and scientists believe another strong quake will impact the region again at some point in the future. Unfortunately, the science isn’t mature enough to tell whether that threat will arrive next week or in 50 years. Either way, with the population of New Madrid Seismic Zone huge compared to the sparsely populated area of the early 1800s, and tens of millions more living in an area that would experience significant ground shaking, there could be a very significant loss of life and property when another major quake strikes here again in the future.