In a stunning display of geology, physics, and chemistry, the Earth is gaining new land while also creating hazardous hydrochloric acid clouds in the process. We traveled to the only place on the planet where an active volcano is sending fresh plumes of lava into the sea: Hawaii’s Big Island. But more than adding to the real estate of Hawaii’s largest island, the interaction between red-hot lava and comparatively cool sea water creates an explosion with numerous hazards.

We journeyed to this magical site with the expert guides of Kalapana Cultural Tours. The family owned and operated business provides multiple avenues for guests to safely explore the sizzling lava flows on Hawaii’s Big Island. Whether it be through a hike, an exhilarating coastal bike ride, or a boat ride to the point of ocean entry, Kalapana Cultural Tours provides locally born and raised guides to share their knowledge of the volcano that has surrounded -or in some cases, buried- their hometown.

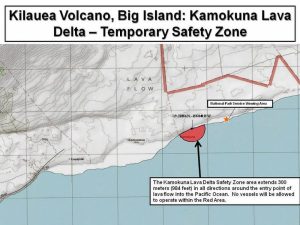

Ikaika Marzo and Andrew Dunn from Kalapana Cultural Tours took us to the ocean entry of the lava flow by boat. In April, the US Coast Guard granted permission to the company to enter the Kamokuna Lava Safety Zone. Mariners were prevented from nearing the entry area in April.

“There was more hazards and dangers that were brought to our attention, so we wanted to implement that safety zone as soon as possible to prevent anything from happening,” said Coast Guard Petty Officer 3rd Class Amanda Lavasser.

In their April letter to Kalapana Cultural Tours, the US Coast Guard wrote, “Based on the documentation and information you provided, including but not limited to vessel’s material condition, safety equipment, redundancies, general safety practices and procedures, specific safety practices and procedures for operating near the lava ocean entry, familiarity with the surrounding waters, and your experience operating as a Coast Guard-credentialed mariner, your request to enter the Kamokuna Lava Safety Zone is granted.”

But even with the approval to near the lava flow, the US Coast Guard reminded Kalapana Cultural Tours of the risks. They wrote, “Although you have demonstrated an apparent ability to mitigate the significant, inherent risks associated with entering the Safety Zone, those risks remain.”

In an active flow in 2000, those risks turned deadly. In November of that year, park rangers from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park discovered the bodies of a man and woman in an advanced state of decomposition. The two bodies were found about 300 feet from the site where the hot lava flow was entering the ocean. With no visible signs of trauma, the park rangers assumed they weren’t hit and killed by flying debris from the volcano, known as tephra. An autopsy report issued two days after the bodies were recovered made a startling discovery: the cause of death was pulmonary edema. Pulmonary edema, or swelling of the lungs, occurs when hydrochloric acid is inhaled. The autopsy also noted that advanced decomposition occurred where skin was exposed to the air, or covered by only a single layer of clothing. As such, the tissue didn’t decompose through natural postmortem decay; very acidic rain was the cause.

Hydrochloric acid is one of many byproducts from active volcanoes. In addition to releasing heat into the area, volcanoes will eject tephra and various gasses into the air. The largest portion of gases released into the atmosphere is water vapor. Other gases include carbon dioxide (CO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), hydrogen fluoride (HF), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen gas (H2), NH3, methane (CH4), and SiF4. Some of these gases are transported away from the eruption on ash particles while others form salts and aerosols. Additional gases are formed when active lava flows burn through vegetation; they also form when lava mixes with water.

In the ocean entry scene at Hawaii’s Kilauea volcano, the only place in the world where an active lava flow is reaching the ocean, extremely hot molten rock enters a relatively cold Pacific ocean. According to the Hawaii Volcano Observatory inside Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, lava flows there reach temperatures of about 1,650 degrees Fahrenheit. Meanwhile, water temperatures around Hawaii average in the low to mid 70s during the winter months to the low to mid 80s during the summer months; even at its warmest, there’s more than a 1,500 degree difference between the molten rock and salt water.

When lava collides with water, the scene is quite explosive.

Depending on the intensity of the flow of lava into the water, different things can happen. Tephra can eject into the area at anytime and at any size. Tephra fragments are generally classified by their size: ash (particles less than 0.08″ in diameter), lapilli, also known as cinders (usually have a diameter between 0.08″ and 2.5″), and volcanic blocks or “bombs” which are larger than 2.5″ in diameter. With the lava and tephra filled with hot gas, as it hits the water, some blobs and rocks can float away, kept buyoant by those gasses. Marzo referred to the boiling-hot, steaming floating rocks around the ocean entry scene as “Hawaiian Icebergs”.

Beyond the gentle roar, rumble, crackle, hissing of the entry itself is the huge cloud plume arising from the sea where water and hot lava meet. The ocean water near the entry is very warm but not boiling; while our boat was a safe distance away, the water was about 5-10 degrees warmer than it was when we left port. During our visit, there was a huge plume rising from the entry point. However, sometimes streams of lava pour into the sea with little or no steam.

According to the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory and the USGS, scientists have found that the outcome of lava-water interaction is determined by the way the interaction occurs. In order for a volume of seawater to boil, lava must heat it to at least 213.15 degrees at the sea surface, and to even higher temperatures below the surface. Obviously, there’s a lot more water than incandescent lava, so if the heat is transferred slowly from lava to seawater, heated water mixes with cooler water, and the boiling point is not reached. Other factors that enhance the rate at which heat is transferred to near-shore water will favor steam formation. Since heat is exchanged at the interface between lava and seawater, processes that increase the surface area of lava exposed to seawater increase steam formation. High lava-flow rates produce more heated surface area.

The cloud that rises from the ocean entry isn’t just water vapor and steam though. This is where harmful hydrochloric acid and other gasses, liquids, and even solids float and fall. Within the dangerous cloud is a substance known as Pele’s Hair. Named after Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes, it can be defined as volcanic glass fibers or thin strands of volcanic glass. The strands are formed through the stretching of molten basaltic glass from lava, usually from lava fountains, lava cascades, and vigorous lava flows. Breathing in these hair-like glass fibers can have the same impact on a body as inhaling fiberglass or asbestos.

The natural, albeit toxic, mixing of chemicals in the sea water at the ocean entry looks and smells bad. In addition to “Hawaiian Icebergs”, sulfur-laden yellow foam and discolored sea water smelling of rotten eggs floated around the area.

The white plume stands in stark contrast to the solidified black lava and the cloud-free blue sky. When the sun isn’t out, the red lava illuminates an eerie red glow inside the plume cloud. Such a visual effect is seen better at the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, where a glow from within Halema’uma’u Crater can be seen. While not close to the ocean here, smoke from the erupting volcano interacting with steam from nearby ground water creates a cloud of chemicals and steam near an area that park visitors can drive to. At night, after a brief walk from a visitor’s parking lot at the crater, guests can watch the plume of smoke dance at the volcano as a lake of lava bubbles and boils beneath.

Scientists are busy studying all of these plumes coming off the volcano at its summit and at the surf. Earlier in 2017, NASA and other scientific organizations launched a pollution forecast study based on data collected in Hawaii. Dr. Vincent Realmuto, who earned a PhD in Geosciences from the University of Arizona, is the leader of a team taking a closer look at pollution in Hawaii. The Hawaii-based team involves NASA, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the United States Geological Society, and a private company called FlySpec, Inc., whose goals include helping to improve both the forecast and the warning time for air pollution advisories.

Air pollution from the volcanoes can be a big problem for Hawaii. Depending on which way the wind is blowing across the state, the smoke and steam plumes and toxic clouds that rise from the volcano can impact distances far away. “In Hawaii, we have 2 major wind patterns. A trade wind pattern where the winds blow consistently out of the northeast and then there is everything else, called Kona winds,” said Dr. Realmuto. He added, “Basically, we think of Kona winds as a wind pattern in which the prevailing wind across the Islands are not out of the Northeast. Generally, it will be from the west, southwest or even south. We have the biggest problems with air quality in Hilo and even Honolulu with Kona winds. Luckily, the tradewinds dominate the weather pattern and occur around 90% of the time. But that other 10% of the time can not be ignored.“

While scientists are studying all aspects of the volcano and its impact on the air and ground around it, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park has become a popular tourist destination. But with lava flowing on the ground and into the water right now, they urge visitors to be vigilant and safe. They advise the following to any guests planning a visit to the amazing sight: “As a strong caution to visitors viewing the ocean entry, there are additional significant hazards besides walking on uneven surfaces and around unstable, extremely steep sea cliffs. Venturing too close to an ocean entry on land or the ocean exposes you to flying debris created by the explosive interaction between lava and water. Also, the new land created is unstable because it is built on unconsolidated lava fragments and sand. This loose material can easily be eroded away by surf, causing the new land to become unsupported and slide into the sea. In several instances, such collapses, once started, have also incorporated parts of the older sea cliff. This occurred most recently on December 31. Additionally, the interaction of lava with the ocean creates a corrosive seawater plume laden with hydrochloric acid and fine volcanic particles that can irritate the skin, eyes, and lungs.”