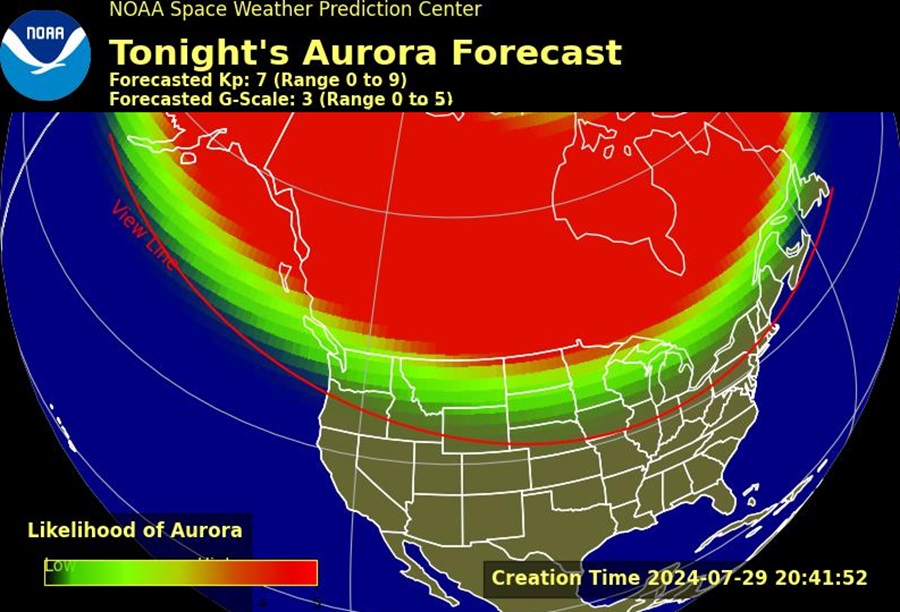

Forecasters with the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) and warning about the prospect of a strong Geomagnetic storm; while there could be many negative impacts around the planet due to the storm, the aurora or “Northern Lights” could make an appearance over a large part of North America. The SWPC has issued Geomagnetic Storm Watches for G1 conditions on July 29, G3 conditions on July 30, and G1 conditions for July 31.

Just like at the weather at the surface of the Earth, the Sun is the primary cause of space weather. At times, the Sun can be thought of as going through a “stormy” period where its surface is more active than normal. When this happens, the Sun can send streams of energized particles out in all directions. When these energized particles interact with the outer reaches of our atmosphere, the aurora borealis (the Northern Lights) and the aurora australis (the Southern Lights) can result.

According to NASA, energetic charged particles from these solar events are carried from the Sun by the solar wind. When these particles seep through Earth’s magnetosphere, they cause substorms. Fast moving particles slam into the thin, high atmosphere, colliding with Earth’s oxygen and nitrogen particles. As these air particles shed the energy they picked up from the collision, each atom starts to glow in a different color. Different interactions with different elements will yield different colors: oxygen gives off green and red light. Nitrogen glows blue and purple.

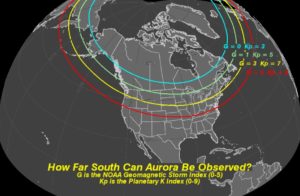

Just as in forecasting a storm on the surface of Earth, there are many ingredients that come together to create aurora and many computer forecast models try to simulate how those ingredients may come together to produce aurora. One common metric to help define the probability and location of aurora displays is based on the Kp index of the storm. The K-index, and by extension the Planetary K-index, are used to characterize the magnitude of geomagnetic storms. The SWPC says that Kp is an excellent indicator of disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic field and is used by SWPC to decide whether geomagnetic alerts and warnings need to be issued for users who are affected by these disturbances. Beyond signifying how bad a geomagnetic storm’s impact can be felt, the Kp index can also help indicate how low, latitude-wise the aurora will be.

The greater the number, the more vibrant aurora can be; in the Northern Hemisphere, a higher Kp index also means the aurora could establish itself high above the United States in southern locations that don’t ordinarily see the Northern Lights. Should the Kp index become greater than the 4 that was initially forecast, aurora currently predicted to be visible in places like northern Michigan or Maine could travel south: a KP index of 7 or more could make the aurora present in clear skies in Boston, Chicago, and Seattle; a Kp index of 9 or more could illuminate the clear night skies of Washington, DC, Saint Louis, Denver, and even Salt Lake City. In past severe geomagnetic storms, the aurora has been visible as far south as Hawaii and the central Caribbean.

However, Kp is only one metric in a very complicated forecast of where aurora may form. The sum amount of energy arriving from the inbound impulses from the Sun, the magnetic configuration of the plasma cloud created by the geomagnetic event, and other states and conditions that exist in the Earth’s magnetosphere all play a role in how the aurora will play-out. And like with weather forecasts for the surface, computer forecast models aren’t perfect and could be off with their analysis on these factors. The real Kp may be much higher or lower than what’s forecast. And even with a high Kp, other components such as the magnetic configuration of the plasma cloud, could dampen the view of the nighttime light show.

Aurora isn’t the only side effect from these geomagnetic storms; the brighter they are, the more harm an overall geomagnetic storm could produce. Electrical system failures, grid failures, communication and navigation system faults, and more could happen if the geomagnetic storm is powerful enough.

On September 1-2 in 1859, a powerful geomagnetic storm struck Earth during Solar Cycle 10. A CME hit the Earth and induced the largest geomagnetic storm on record. The storm was so intense it created extremely bright, vivid aurora throughout the planet: people in California thought the sun rose early, people in the northeastern U.S. could read a newspaper at night from the aurora’s bright light, and people as far south as Hawaii and south-central Mexico could see the aurora in the sky. This day became known as the “Carrington Event.” The event severely damaged the limited electrical and communication lines that existed at that time; telegraph systems around the world failed, with some telegraph operators reporting they received electric shocks.

According to NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center, the best chance for aurora will be between 1am and 5am tonight. To view, simply look up at anytime in skies free of clouds and any light. Depending on the actual potency of the disturbance and other factors, the aurora could appear as a brilliant waving ribbon of color …or a faint, flickering hint of distant color in the night sky. Or it can be both. Signing up for free services and apps, such as Aurorasaurus, can alert you to the possible presence of aurora outside. Following social media sites, such as X, is also a way to find out where/when people are seeing aurora in their night skies.