Blizzard conditions are now likely with a bomb cyclone projected to impact parts of the Great Lakes and Northeast later this week in the days leading up to Christmas. A meteorological process known as explosive cyclogenesis will create a bomb cyclone, which is an area of intense low pressure which drops significantly over a short period of time. Generally, an area of low pressure must drop by more than 24 mb in a 24 hour period, although the criteria changes at different latitudes. Bomb cyclones are common over the Pacific Ocean, especially the North Pacific near Alaska, and will sometimes form in the Atlantic from time to time; they could happen on land sometimes too, although it’s very rare. And it looks like such a rare scenario is about to unfold over the coming days.

Models and their respective ensembles have remained locked into solutions depicting rapid cyclogenesis Thursday into Friday as an area of low pressure tracks from southern Illinois to lower Michigan. Various models depict explosive deepening of this low with central pressure dropping as much as 25-35mb in 24 hours. This type of explosive intensification is quite rare in this region and is expected to result in extremely powerful and potentially damaging winds late Thursday night and especially Friday around the Great Lakes and beyond.

The GFS and ECMWF are among many computer models meteorologists use to assist in weather forecasting. While meteorologists have many tools at their disposal to create weather forecasts, two primary global forecast models they do use are the ECMWF from Europe and the GFS from the United States. While the models share a lot of the same initial data, they differ with how they digest that data and compute possible outcomes. One is better than the other in some scenarios, while the opposite is true in others. No model is “right” all the time. Beyond the ECMWF and GFS models, there are numerous other models from other countries, other academic institutions, and private industry that are also considered when making a forecast.

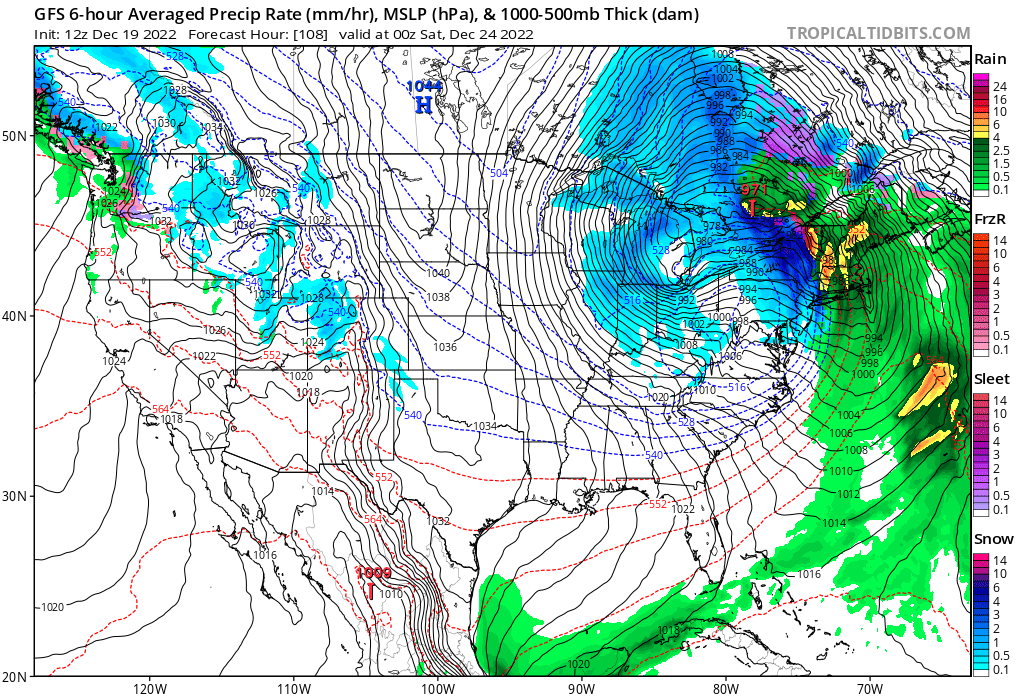

This afternoon, both the GFS and ECMWF forecast models were in good agreement with their forecast solution, showing the bomb cyclone taking shape near the Great Lakes. However, there are differences in their output, which could make the difference between a white or non-white Christmas. Both models depict a surge of moisture and mild air rising north along the coastal plain ahead of the low; this will drive wind-whipped rain, instead of snow, to not only the I-95 corridor, but throughout much of New England too.

Bitter cold Arctic air will wrap in behind this bomb cyclone, and the GFS and ECMWF differ with what that cold air influence will have. In the case of the GFS, there’s enough lingering moisture left-over to turn rain to snow throughout the I-95 corridor from Virginia to Boston and all points north and west. Snow will accumulate north and west of I-95 with little to no accumulations near it and to points south and west. Meanwhile, in addition to wrapping cold air around the system, the ECMWF also rotates in dry air. In its solution, it dries out the atmospheric column above the surface before it has a chance to cool enough to create snow. While the ECMWF solution will produce lake effect snows over upstate New York, it doesn’t produce much in the way of any snow south or east of there, which would leave the I-95 corridor dry and cold by Christmas Eve night.

Both storms will drive temperatures to well-below normal, and for many across the northeastern U.S., this will be the coldest Christmas in many years. But for those hoping for a White Christmas, the closer you are to the center of and/or the west side of the bomb cyclone, the better your chances of significant snowfall.

Both global forecast models, the GFS and ECMWF, show packed isobars wrapped around an intense low pressure system in the Great Lakes and Northeast. Isobars on a weather map reflect lines of equal atmospheric pressure; the closer they are, generally the more windy it becomes. Because of how tightly packed they are in the modeled forecast, it suggests the presence of very strong winds. With falling and/or blowing snow and high winds, the definition of a blizzard could be reached in some areas.

While most people associate a blizzard with a heavy snow event, a blizzard is officially defined by wind and visibility –and not by accumulation. To reach official blizzard criteria, you must have blowing and/or falling snow with winds of at least 35 mph, reducing visibilities to a quarter of a mile or less, and such conditions must last for at least three hours. Winds lofting the current snow pack and reducing visibilities without any falling snow is called a ground blizzard and is just as hazardous as a blizzard with freshly falling snow.

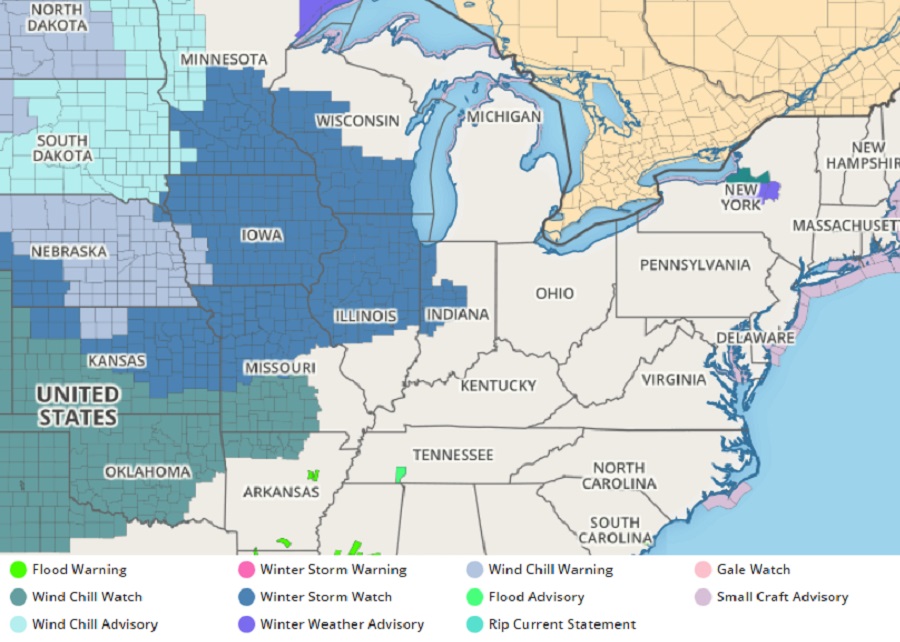

With severe winter storm conditions or blizzard conditions possible, the National Weather Service has started to issue Winter Storm Watches. With time, these watches could be upgraded to Winter Storm Warnings or Blizzard Warnings.

The National Weather Service in Chicago warns, “If current guidance is close to verifying, then conditions Friday could rival the 2011 Groundhog Day blizzard, particularly in open areas. Travel would become extremely dangerous and life threatening, particularly in light of the bitterly cold temperatures during the height of the storm.”

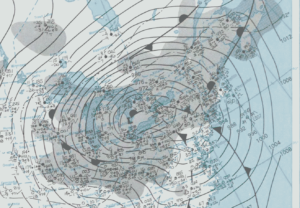

Comparisons are also being made to the Great Blizzard of 1978. That storm, similar to this one, was a rapidly deepening low pressure system that created blizzard conditions across the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes regions. From Wednesday January 25 through Friday January 27, the blizzard hit communities hard. That storm claimed 71 lives and cost at least $100 million in damages. Up to 52″ of snow fell while the barometric pressure dropped to an amazingly low 956 mb, making it the third lowest non-tropical atmospheric pressure ever recorded over land in the U.S. at the time.

It is still too soon to know where the heaviest snow will fall and where the worst of the blizzard conditions will be. For now, it appears that the heaviest snow will fall across southern Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, northern Illinois and Indiana, western Pennsylvania and New York, and the highest terrain of West Virginia. Somewhere in this zone is where blizzard conditions are likely to form, and they may be centered around Chicago, Illinois to western Michigan.

Powerful winds from this storm will blow across a much broader area than where snow is expected, and such a wind event could create travel headaches far from the low center. While snow and possible blizzard conditions could cripple Chicago’s airports, wind could also impact operations as far away as Washington, DC’s Dulles and Reagan National airports, Philadelphia and Baltimore-Washington airports, and the New York City area airports including Newark Liberty Airport in New Jersey.

Because temperatures will drop quickly behind the storm, there will also be widespread black ice concerns as any non-treated wet surface freezes on Christmas Eve as the storm exits the U.S.. While it’s too soon to know where that specific hazard will set-up, it’s important that people traveling around the Great Lakes or Northeast know such a threat exists even if areas get little to no snowfall from the bomb cyclone.