In a dynamic environment with an active erupting volcano, tropical downpours that create flash floods, high elevation snowstorms, and the occasional threat of hurricanes, Hawaii’s Big Island finds itself in the middle of an exceptionally dynamic treasure trove of atmospheric and earth science data. To help quantify what’s in the air and what comes down is a very busy Data Collection Office (DCO) at Hilo’s International Airport.

Staffed with meteorologists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the daily highlights of the office include the launching of two critical weather balloons every day. The data from those balloons helps build a profile of what’s what with the atmosphere above the surface, providing key forecasting clues to meteorologists and their machines around the world.

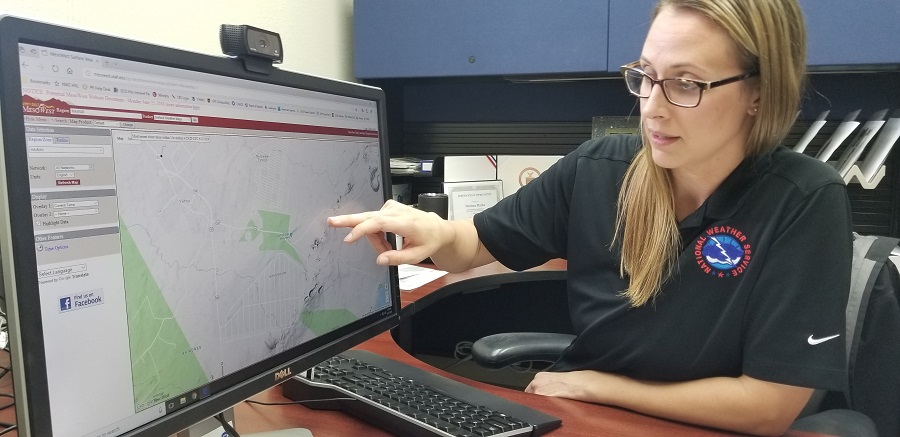

Deanna Marks, the Official in Charge of the DCO, provided us with a tour of their facility and the chance to experience a weather balloon launch. ” Our number one priority is to stay on top of the winds,” Marks said, describing one key use of the data: understanding where volcanic gas and ash from the ongoing Kilauea eruption will go.

This spring, fissures opened up in Kilauea’s Lower East Rift Zone, spewing hot lava into residential neighborhoods and a huge volume of volcanic gasses into the air. While volcanic activity was busy in the lower Puna District, more than 20 miles away at Kilauea’s summit, seismic events tied to the collapsing caldera there would eject rocks and ash into the air. In the first weeks of the 2018 Eruption, ash would eject regularly from the summit into the air, dusting down-wind neighborhoods with abrasive volcanic ash. Unlike ash you’d see around a campfire, volcanic ash is pulverized rock, ground into tiny fragments that can harm property and life.

Beyond ash that you can see and touch, the volcano has also been releasing huge amounts of sulfur dioxide gas. At the very least, an irritant to healthy people, or harmful or worse to those with a compromised respiratory system, sulfur dioxide can create big problems for people. Sulfur dioxide also disrupts the photosynthesis process in plants and mixes with rain to create acid rain; together, forests and farms can be wiped out should this gas envelop them.

“Our community is extremely important. We want to be timely and accurate with wind forecasts and on-point with observations, ” Marks said. Sharing weather data with Hawaii County Civil defense in ongoing briefings is one way weather information is helping advise authorities to keep the population safe from Kilauea’s hazards.

And there it goes!

We captured today’s @noaa weather balloon launch that’ll not only help w/global forecast models, but w/an understanding of the wind profile above #KilaueaEruption for ash/vog dispersion. This is from our FacebookLive today in Hilo. #HIwx pic.twitter.com/ui3svwsjgX— the Weatherboy (@theWeatherboy) June 23, 2018

Beyond the volcano though, data is observed and collected for important purposes in the weather world. Data captured by weather balloons is used by global forecast models to not only provide better forecasts for Hawaii, but better forecasts around the Pacific and the United States. By supplementing data captured by weather satellites, these balloon launches provide timely data quickly to NOAA.

The weather balloon carries a device called a radiosonde high into the atmosphere to collect important data. The radiosonde is a small, expendable instrument package that is suspended about 80 feet below a large balloon inflated with hydrogen. The hydrogen in the balloon is generated at the Hilo DCO site. As the radiosonde rises at about about 1,000 feet/minute, sensors on it measure profiles of pressure, temperature, and relative humidity. These sensors are linked to a battery powered radio transmitter that sends the sensor measurements to a sensitive ground tracking antenna. Wind speed and direction aloft are also obtained by tracking the position of the radiosonde in flight using GPS or a radio direction finding antenna. The radio signals received by the tracking antenna are converted to meteorological values and from these data significant levels are selected by a computer, put into a special code form, and then transmitted to data users. High vertical resolution flight data, among other data, are also archived and sent to the NOAA National Climatic Data Center.

When released, the weather balloon is about 5 feet in diameter. As it rises into thin air, it gradually expands as a result of the difference in air pressure with the balloon and the air that surrounds it. When the balloon reaches a diameter of 20 to 25 feet in diameter, it bursts. A small parachute slows the descent of the radiosonde, minimizing the danger to lives and property of the small lightweight device.

Eventually the weather balloon bursts and the radiosonde makes its way back to earth. Often, the radiosonde launched from Hilo will land in the nearby Pacific Ocean or occasionally on the slopes of nearby Mauna Loa. The radiosonde itself is made to be as environmental friendly as possible; it’s made of foam, cardboard, and a small amount of electronics. Meteorologist Technician Michael Reilly said, “We try to be as green as possible. There are components that are biodegradable. And on top is a bag attached that says, ‘remove bag for mailing instructions.'” People that find these radiosondes are encouraged to mail them back in the bag to NOAA for reconditioning and recycling. Marks says the reconditioning office will try to harvest as much of the radiosonde that wasn’t damaged in the fall, reusing it for future missions. “Especially out here near the ocean, we want to be sure we’re good stewards of the land and of the ocean. Even the parachute that appears to be plastic is actually photodegradable, so the sun will break it down so we’re not adding additional plastic there (to the environment),” Marks adds.

Worldwide, there are over 800 upper-air observation stations and through international agreements data are exchanged between countries. Most upper air stations are located in the Northern Hemisphere and all observations are usually taken at the same time each day every day of the year. In the United States, the National Weather Service launches balloons at 92 stations; 69 are in the continental U.S., 13 are in Alaska, 9 are in the Pacific (including Hilo DCO) , and 1 is in Puerto Rico.

The Hilo DCO is also responsible for what Marks calls “ground truths.” By examining weather data collected by official weather stations or trained observers, the NOAA office can also relay important information onto other National Weather Service offices. As an example, information about a heavy rain event on Hawaii could be relayed by the DCO office to the National Weather Service office in Honolulu, where Flash Flood Warnings or advisories could be issued for the Big Island.

Beyond data collection on the ground and the air, the Hilo DCO also participates in various outreach programs with the community. Whether their meteorologists are out visiting schools or hosting tours of their facility, providing Skywarn training, or participating in county Earth Day events, the meteorologists at this office bring weather awareness and education to life as often as they can.