On this day in 2003, disaster struck over the skies of Texas and Louisiana. As it was re-entering the atmosphere after a 16-day scientific mission, Space Shuttle Columbia was destroyed at about 09:00 ET.

The Columbia Accident Investigation Board determined that a hole was punctured in the leading edge on one of Columbia’s wings, made of a carbon composite. The hole had formed when a piece of insulating foam from the external fuel tank peeled off during the launch 16 days earlier and struck the shuttle’s left wing. During the intense heat of re-entry, hot gases penetrated the interior of the wing, destroying the support structure and causing the rest of the shuttle to break apart.

The seven crew members who died aboard this final mission were: Rick Husband, Commander; William C. McCool, Pilot; Michael P. Anderson, Payload Commander; David M. Brown, Mission Specialist 1; Kalpana Chawla, Mission Specialist 2; Laurel Clark, Mission Specialist 3; and Ilan Ramon, Payload Specialist 1.

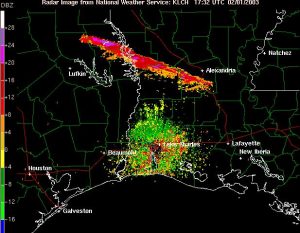

As the shuttle disintegrated over Texas and Louisiana upon re-entry to the Earth’s atmosphere, the event was recorded on NEXRAD weather RADAR as the debris field from the shuttle spread across the region on the tragic day. This video clip shows that weather RADAR as debris fell to the ground. While ground clutter produces a ring of false echoes around the RADAR site, a band of debris form over Texas and Louisiana as the accident unfolds.

As a result of this disaster, the Space Shuttle program was put on hold for more than two years as NASA and related scientists explored the cause and to develop plans to avoid such a catastrophe in the future.

These are the last moments of the fateful flight, as recorded by NASA:

- 8:00: Mission Control Center Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain polled the Mission Control room for a GO/NO-GO decision for the de-orbit burn. All weather observations and forecasts were within guidelines set by the flight rules, and all systems were normal.

- 8:10: The Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) told the crew that they were GO for de-orbit burn.

- 8:15:30 (EI-1719): Husband and McCool executed the de-orbit burn using Columbia’s two Orbital Maneuvering System engines. The Orbiter was upside down and tail-first over the Indian Ocean at an altitude of 175 miles (282 km) and speed of 17,500 miles per hour (7.8 km/s) when the burn was executed. A 2-minute, 38-second de-orbit burn during the 255th orbit slowed the Orbiter to begin its re-entry into the atmosphere. The burn proceeded normally, putting the crew under about one-tenth gravity. Husband then turned Columbia right side up, facing forward with the nose pitched up.

- 8:44:09 (EI+000): Entry Interface (EI), arbitrarily defined as the point at which the Orbiter entered the discernible atmosphere at 400,000 feet ( 76 mi), occurred over the Pacific Ocean. As Columbia descended, the heat of reentry caused wing leading-edge temperatures to rise steadily, reaching an estimated 2,500 °F during the next six minutes.

- 8:48:39 (EI+270): A sensor on the left wing leading edge spar showed strains higher than those seen on previous Columbia re-entries. This was recorded only on the Modular Auxiliary Data System, which is a device similar to an airplane’s flight data recorder, and was not sent to ground controllers or shown to the crew.

- 8:49:32 (EI+323): Columbia executed a planned roll to the right. Speed: Mach 24.5. As such, Columbia began a banking turn to manage lift and limit the Orbiter’s rate of descent and heating.

- 8:50:53 (EI+404): Columbia entered a 10-minute period of peak heating, during which the thermal stresses were at their maximum. Speed: Mach 24.1; altitude: 243,000 feet.

- 8:52:00 (EI+471): Columbia was about 300 miles west of the California coastline. The wing leading-edge temperatures usually reached 2,650 °F at this point.

- 8:53:26 (EI+557): Columbia crossed the California coast west of Sacramento Speed: Mach 23; altitude: 231,600 feet (43.86 mi).

- 8:53:46 (EI+577): Various people on the ground saw signs of debris being shed. Speed: Mach 22.8; altitude: 230,200 feet ( 43.60 mi). The super-heated air surrounding the Orbiter suddenly brightened, causing a streak in the Orbiter’s luminescent trail that was quite noticeable in the pre-dawn skies over the West Coast. Observers witnessed four similar events during the following 23 seconds. Dialogue on some of the amateur footage indicates the observers were aware of the abnormality of what they were filming.

- 8:54:24 (EI+615): The Maintenance, Mechanical, and Crew Systems (MMACS) officer told the Flight Director that four hydraulic sensors in the left wing were indicating “off-scale low”. In Mission Control, re-entry had been proceeding normally up to this point. “Off-scale low” is a reading that falls below the minimum capability of the sensor, and it usually indicates that the sensor has stopped functioning, due to internal or external factors, not that the quantity it measures is actually below the sensor’s minimum response value.

- 8:54:25 (EI+616): Columbia crossed from California into Nevada airspace. Speed: Mach 22.5; altitude: 227,400 feet (43.07 mi). Witnesses observed a bright flash at this point and 18 similar events in the next four minutes.

- 8:55:00 (EI+651): Nearly 11 minutes after Columbia re-entered the atmosphere, wing leading-edge temperatures normally reached nearly 3,000 °F.

- 8:55:32 (EI+683): Columbia crossed from Nevada into Utah. Speed: Mach 21.8; altitude: 223,400 feet (68.1 km; ( 42.31 mi).

- 8:55:52 (EI+703): Columbia crossed from Utah into Arizona.

- 8:56:30 (EI+741): Columbia began a roll reversal, turning from right to left over Arizona.

- 8:56:45 (EI+756): Columbia crossed from Arizona to New Mexico. Speed: Mach 20.9; altitude: 219,000 feet (41.5 mi).

- 8:57:24 (EI+795): Columbia passed just north of Albuquerque, NM.

- 8:58:00 (EI+831): At this point, wing leading-edge temperatures typically decreased to 2,880 °F (1,580 °C).

- 8:58:20 (EI+851): Columbia crossed from New Mexico into Texas. Speed: Mach 19.5; altitude: 209,800 feet (39.73 mi). At about this time, the Orbiter shed a Thermal Protection System tile, the most westerly piece of debris that has been recovered. Searchers found the tile in a field in Littlefield, Texas, just north and west of Lubbock.

- 8:59:15 (EI+906): MMACS told the Flight Director that pressure readings had been lost on both left main landing-gear tires. The Flight Director then instructed the Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) to let the crew know that Mission Control saw the messages and was evaluating the indications, and added that the Flight Control Team did not understand the crew’s last transmission.

- 8:59:32 (EI+923): A broken response from the mission commander was recorded: “Roger, uh, bu – [cut off in mid-word] …” It was the last communication from the crew and the last telemetry signal received in Mission Control.

- 8:59:37 (EI+928): Hydraulic pressure, which is required to move the flight control surfaces, was lost at about 8:59:37. At that time, the Master Alarm would have sounded for the loss of hydraulics, and the shuttle would have begun to lose control, starting to roll and yaw uncontrollably, and the crew would have become aware of the serious problem.

- 9:00:18 (EI+969): Videos and eyewitness reports by observers on the ground in and near Dallas indicated that the Orbiter had disintegrated overhead, continued to break up into smaller pieces, and left multiple ion trails, as it continued eastward. In Mission Control, while the loss of signal was a cause for concern, there was no sign of any serious problem. Before the orbiter broke up at 9:00:18, the Columbia cabin pressure was nominal and the crew was capable of conscious actions. The crew module remained mostly intact through the breakup, though it was damaged enough that it lost pressure at a rate fast enough to incapacitate the crew within seconds, and was completely depressurized no later than 9:00:53.

- 9:00:57 (EI+1008): The crew module, intact to this point, was seen breaking into small subcomponents. It disappeared from view at 9:01:10. The crew, if not already dead, were killed no later than this point.

- 9:05: Residents of north central Texas, particularly near Tyler, reported a loud boom, a small concussion wave, smoke trails and debris in the clear skies above the counties east of Dallas.

- 9:12:39 (EI+1710): After hearing of reports of the shuttle being seen to break apart, Entry Flight Director LeRoy Cain declared a contingency (events leading to loss of the vehicle) and alerted search-and-rescue teams in the debris area. He called on the Ground Controller to “lock the doors”, meaning no one would be permitted to enter or leave until everything needed for investigation of the accident had been secured. Two minutes later, Mission Control put contingency procedures into effect.\

The anniversary of the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster comes just days after the anniversary of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. On January 28, 1986, the Challenger was destroyed during liftoff into space, killing all seven on board. To mark the memory of those lost in these Space Shuttle accidents and the Apollo 1 mission, NASA declared January 31 a Day of Remembrance. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D/TX), from the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology said, “NASA’s annual Day of Remembrance is a powerful reminder of the sacrifices made by American men, women, and their families in the pursuit of space exploration. Today we honor the crews of the Columbia and Challenger space shuttles and Apollo 1, a tribute particularly noteworthy this year, the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 1 accident. I am so grateful to the entire NASA family for their contributions to our country.”