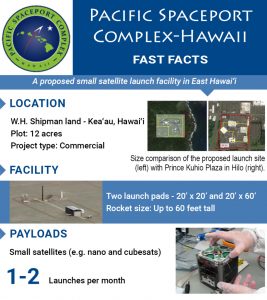

Plans to run a small spaceport from the Big Island of Hawaii have hit a dead-end, dealing a deathblow to what many thought would be a way to energize the local economy and education system with inspirational space-based endeavors. Alaska Aerospace was hoping to lease land from W.H. Shipman and use the space of roughly the handicapped parking section of a local mall to launch as many as two small rockets into space each month. W.H. Shipman decided to end the pursuit and terminate conversations with the Alaska-based corporation. Without any other possible options in Hawaii, Alaska Aerospace is abandoning their plans to work in the Aloha State. This was the second company to attempt to leverage Hawaii’s valuable location to launch rockets into space; no other companies are pursuing the possibility now.

“We began the preliminary discussions with Alaska Aerospace with an open mind and without a long-term commitment; only the understanding that we would explore the concept of building the proposed Spaceport Project on our land in Keaʻau. Our hope was to support a nucleus for the development of the aerospace industry in Hilo and Keaʻau, in order to provide jobs and educational opportunities. Early on in the process, we made it clear that our final decision to participate would be based on as much factual information as we could obtain in order to consider whether the project was right for our land, our family, and our community. After evaluating all available information, at this time we do not feel that the proposed project is the best fit for W.H. Shipman, Limited”, said Peggy Farias, President of W. H. Shipman in a written statement.

We asked Farias if there was any one issue that led to their decision. Farias responded, “Our decision was based on all of the information available to us, including our family’s response to the project, the community response to the project, both positive and negative , the potential benefits of the project, and a preliminary internal draft of the EA (Environmental Assessment). When we looked at the big picture formed by all of these factors, we felt that the project just wasn’t a good fit for us.”

Alaska Aerospace President Mark Lester told us he’s disappointed in the decision not to proceed, but respects the decision made. “While we are disappointed Hawaii didn’t work out as envisioned for a light-lift rocket launch facility, we respect and support Shipman’s decision. Both Shipman and Alaska Aerospace have consistently stated that we would pursue an organized process and conduct careful research before making final decisions. It the project didn’t fit, we all agreed we would not force it. Closing this pursuit honors our commitment to the Shipman family, our partners, and the community,” said Lester.

Lester hopes that beyond this failed spaceport attempt, that Hawaii will continue to pursue high-tech adventures. Lester said, “The upside potential to the local economy and commercial space community was worth trying. We appreciate the courage and open minded nature of the Shipman family and our other Hawaii-based partners to explore this concept with us. I also want to thank the many public supporters we met during our exploratory public meetings and small group discussions on the Big Island and across Hawaii. While we weren’t able to achieve the desired outcomes of this project, I hope the community can apply lessons learned from this effort to achieve the promise of future high-tech endeavors.”

Rodrigo Romo of PISCES is disappointed too. Romo serves as Program Director for the Hilo, Hawaii-based Pacific International Space Center for Exploration Systems (PISCES), a state-funded aerospace agency operating under the Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism (DBEDT). PISCES’ core mission is to develop and grow the aerospace industry in Hawaii through “Applied Research, Workforce Development and Economic Development initiatives” according to their mission statement. Romo told us, “I believe this is a missed opportunity for the Big Island to develop a new industry cluster. We knew from the beginning of the project that ultimately Shipman would have the final word on the use of the land. They have been very good to work with, open and honest, and in the end they made the decision based on what they see as the best option for their company. ”

Romo adds that the decision by Shipman to abandon the project “certainly presents a setback” to Hawaii’s aerospace industry. “The demand for small vehicle launch sites is still growing and there are companies that have expressed interest in Hawaii as a launch site. But with the current environment, I am not sure many companies will be willing to invest their time and money into Hawaii. However, we in PISCES will continue to promote and push forward for the advancement of the aerospace industry to help diversity the economy of the state.”

Lester agreed that the market for small vehicle launch sites continues to grow. “Modern society’s dependence upon space-based technology and services from and through space continues to emerge, grow, and evolve. There are very few orbital-class spaceports and the need to launch safely and efficiently is expected to outstrip existing spaceport capacity.” Lester told us that his company will continue to explore potential spaceport locations outside of Hawaii to meet low-inclination launch needs to complement their existing launch capability to polar and high-inclination orbits at Kodiak Island, Alaska.

Hawaii, especially Hawaii’s Big Island, provides the best location within the United States to launch such satellites into equatorial orbit. Rockets use fuel to escape the Earth’s gravity, using thrust to achieve escape velocity. Because the Earth is round, as it relates to Space, objects close to the Equator are moving faster than those closer to the poles –by about 1,040mph. By launching close to the equator, a rocket can use that much less fuel because it’s already moving in excess of 1,040mph to start with. Rockets farther away from the Equator need to consume more fuel to reach those speeds. Because a launch location in Hawaii is roughly 600 miles farther south than NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, rockets can be more efficient launching from the Aloha State. International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) also prevent many companies from launching outside of the United States. ITAR is a United States regulatory regime designed to restrict and control the export of defense and military related technologies to safeguard U.S. national security interests. Because some commercial payloads may be sensitive to ITAR restrictions, launching from Hawaii could theoretically be the most south place such a launch could occur without running afoul of ITAR for equatorial orbits.

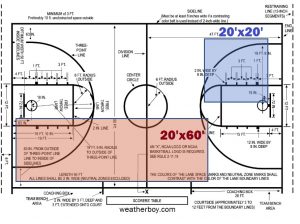

While some may think of a “spaceport” of being large and imposing, the Alaska Aerospace plan was very tiny. Unlike larger spaceports in the U.S. Mainland such as giant NASA Kennedy Space Center in Florida or the relatively small NASA Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, the Alaska Aerospace plan called for constructing two small launch pads that could both fit within the inside of a typical basketball court.

Not everyone is sad to see the proposed spaceport plan fail to launch. One such person is Terri Napeahi; while running for an unsuccessful bid for local office in 2018, Napeahi has been successful in leading a voice in the public and in social media protesting plans for the spaceport. Napeahi said this proposal is just another burden on a growing list of burdens and hardships her community is facing.

“Here on the Big Island, you know we had to endure so many different proposals and development proposals that were detrimental to our family’s lives,” Napeahi told us. “We’re now living the compounded impact of several toxic release inventory companies, especially here in Hilo where the majority of the industry is in place, where we have a harbor and we have the airport.” Napeahi took time explaining to us the plight of Hawaiians living on the island and how they’ve been treated as an afterthought in political decisions and development plans over the decades. In describing how Hawaiian Homeland residents have been treated over the years, she described one situation where family members were forced off the land they were living on to make way for Hilo International Airport. “They had no say; it was an executive order done by the governor and their families had to move and make way for a runway. I live right smack in front of touch and go and so we’ve had to endure the noise. And it hasn’t been mitigated since it was put there in the early sixties. My family has to endure a lot of health impacts, like fumes and the sound, and it’s unfortunately never been mitigated.” Napehi just isn’t against the spaceport, though. At a community open house for the proposed spaceport earlier this year, we asked Napeahi point blank: “Is it safe to say you’re not just against the spaceport, you’re against any industry in this area?” She answered with a simple “yes.”

Hawaii is no stranger to space science. The Maunakea Observatories are located within a 90 minute drive of the proposed spaceport. Located on the summit of Mauna Kea, 13 independent multi-national astronomical research facilities peer into the sky to study different aspects of space. Nearby volcano Mauna Loa is also home to the HI-SEAS lab. Short for Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, HI-SEAS is a habitat on an isolated Mars-like site on the Mauna Loa side of the saddle area on the Big Island of Hawaii at approximately 8,200 feet above sea level. Through last year, studies were done with people who would live there for months at a time in a Mars-like environment. The site is being transformed now to simulate moon-based missions planned by the U.S. in the years ahead. NASA has been working on a variety of initiatives in Hawaii due to its unique location, terrain, and volcanic geology for projects ranging from robotics to space materials sciences. Hawaii was also home for famed astronaut Ellison Onizuka; born in Kealakekua, Hawaii, Onizuka became the first Asian American in space and the first person of Japanese ancestry to reach Space. He flew on Space Shuttle Discovery on mission STS-51-C and served as a Mission Specialist for STS-51-L, the ill-fated Space Shuttle Challenger mission that exploded shortly after take-off. Many places are named in honor of Onizuka in Hawaii, including the Big Island’s Kona International Airport which is officially known as the “Ellison Onizuka Kona International Airport.”

While W.H. Shipman will not move forward on the Alaska Aerospace proposal, they are keeping the door open to future possibilities. Farias tells us, “We evaluate all proposed projects on a case-by-case basis, so our decision to not participate is specific to this project at this point in time. We remain committed to bringing economic and educational opportunities to Puna, and part of that is encouraging the development of new industries such as aerospace. While we are unlikely to host rockets on our land in the foreseeable future, we are keeping in contact with the stakeholders on this project and would certainly consider future project proposals from the aerospace industry.”

While rockets won’t launch from W.H. Shipman land next year as Alaska Aerospace had hoped, Farias hopes their company’s land could play a role in the aerospace industry. “I think Hawaii has a lot to offer the aerospace industry, and that the aerospace industry could bring a lot of benefits to Hawaii, but I think developing that industry in Hawaii needs to be done very carefully, with representatives from a range of groups in our community having a voice at the table,” Farias said. “Our land could play a role in the future if we find the right project.”