A state-run corporation in Alaska is proposing to build a mini-spaceport on the Big Island of Hawaii which could jump start an island already invested in the space sciences. While images of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center complex come to mind for many when thinking of a “spaceport”, Alaska Aerospace is hoping to build a comparably tiny launch facility in a non-populated portion of Hawaii Island’s east coast. A new generation of small launch vehicles and even smaller space-bound cargo don’t need much space to leave the Earth’s atmosphere and Alaska Aerospace hopes to build a new spaceport right-sized for such small rockets on the Big Island.

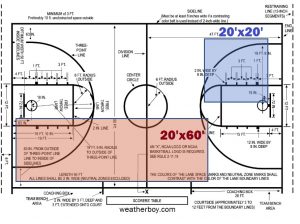

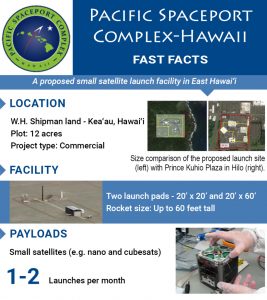

Known as the “Proposed Pacific Spaceport Complex–Hawai`i” or PSCH for short, the launch facility would have an exceptionally small footprint. Two launch pads would be built at the site, one being 20′ x 20′, the larger being 20′ x 60′. In comparison, both of these pads could fit inside a standard basketball court and still leave plenty of room to play. The two launch pads would be built along with a horizontal integration facility (HIF). Basically a garage for rockets, mission specialists tasked to a specific launch would make final preparations with a launch vehicle under cover in there prior to bringing the rocket out to a pad for launch. The two pads and HIF would be contained within a leased 14 acre parcel in an area currently not used but zoned for agriculture. The fenced-in parcel would be tiny too, roughly a third of the size of the parking lot of the Prince Kuhio Mall, a popular shopping area many in Hilo visit. No other significant infrastructure, including fuel storage, is planned for the site.

Alaska Aerospace, which was established by the State of Alaska to develop a high technology aerospace industry in the state of Alaska, would only serve as a launch facility. The manufacturing, servicing, and monitoring of the rocket would be done elsewhere by other companies. Alaska Aerospace CEO Craig Campbell used an analogy with Hilo Airport to describe his company’s vision for the spaceport with us. Alaska Aerospace would be the “airport”, providing the necessary place for rockets to launch from much like an airport provides airlines with a place to land and depart their planes. Alaska Aerospace isn’t in the rocket business themselves, much like Hilo Airport doesn’t operate their own airplanes. Instead, Campbell told us companies like Rocket Lab would use this spaceport to launch their rockets. While companies like Hawaiian Airlines depend on customers to stay in business, the same is true in the rocket business. Rather than shuttling passengers and cargo around, companies like Rocket Lab would take their own customer’s cargo to space.

Rockets launching from Hawaii would be much, much smaller than the ones used at spaceports in Virginia, California, and Florida on the Mainland. On Hawaii, tourists often explore the island’s black sand beaches, volcanoes, waterfalls, and more using Roberts Hawaii bus tours. The length of their typical bus is about the length of the rockets proposed to be used in Hawaii; the rockets are also about half the width of those buses. Rockets would be as short as 20 feet to as tall as 60 feet at this location. Because of their small size, rockets launching from Hawaii would be much more quiet than their larger versions on the U.S. mainland. According to KSF, the Honolulu, Hawaii-based engineering company responsible for completing an environmental assessment for the proposed site, the noise coming from a clap of thunder would be louder than that of a launching rocket in Hawaii. KSF writes that the noise would be “comparable to (equal to or less than) the sound of thunder (120 decibels [dB]), ocean waves (60-78 dB), coqui frog (90 dB all night), lawn mower (90-110 dB), garbage disposal (80 dB), and normal conversation (60-90 dB).” They add, “The farther you are from the complex, the less noise you will hear. At greater than 9,000 feet away from the launch pad, the noise level would be less than 98 dB.” The actual launch would take about 90 seconds; after that time, there would be no visible or audible reminder that a rocket had launched.

As an extra safety measure, spaceports shut down access to nearby land, water, and air during a launch in partnership with the FAA, the Coast Guard, and local authorities. While East Coast launches have stay-away zones of many miles due to larger rockets launching there, Alaska Aerospace says such a zone in Hawaii would extend no more than 6,561 feet from the launch pad. Campbell says such a closure would happen within 2-3 hours of a launch attempt and that launch times would be optimized to be as least disruptive as possible to boat and air traffic in the area. Because of its size and location, the proposed spaceport site would not interfere with operations at Hilo International Airport. It also wouldn’t impact any residential areas; the proposed site would be on land leased by the WH Shipman Company and would be surrounded by more undeveloped land owned by the WH Shipman Company. Campbell says because the area is currently inaccessible and undeveloped, a road going to the spaceport could open up other land to agriculture. The launch site is close to a large macadamia nut grove and the Mauna Loa Macadamia Nut factory and better access into this area could lead to more farming including larger tree farms which could serve as an additional landscape buffer to the spaceport’s launchpads.

Rockets in Hawaii would bring very small satellites to orbit. These next-generation satellites, also called CubeSats and NanoSats, orbit the earth and are primarily used for communication, navigation and mapping. Nanosatellites, which weigh between 2 and 22 pounds, are between the size of a Rubik’s cube and a rice cooker, according to PSCH. Microsatellites weigh between 22 and 220 pounds and are sized between a microwave oven and a dorm room refrigerator.

Rockets would use different fuels, primarily rocket fuel, which is similar to jet fuel, and liquid oxygen. According to KSF, as an example, Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket carries about 1,000 gallons of rocket fuel and about 2,500 gallons of liquid oxygen. In comparison, A Hawaiian Airlines jet flying from Hilo to Honolulu and back burns approximately 2,000 gallons of jet fuel. Fuel would be trucked to the launch pad just as gasoline is trucked to gas stations.

The PSCH proposal calls for upwards of 24 launches per year; it’s possible some months may see 1 or no rockets launch, while others may see 2 or more launch.

Hawaii, especially Hawaii’s Big Island, provides the best location within the United States to launch such satellites into equatorial orbit. Rockets use fuel to escape the Earth’s gravity, using thrust to achieve escape velocity. Because the Earth is round, as it relates to Space, objects close to the Equator are moving faster than those closer to the poles –about 1,040mph. By launching close to the equator, a rocket can use that much less fuel because it’s already moving in excess of 1,040mph to start with. Rockets farther away from the Equator need to consume more fuel to reach those speeds. Because a launch location in Hawaii is roughly 600 miles farther south than NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, rockets can be more efficient launching from the Aloha State. International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) also prevent many companies from launching outside of the United States. ITAR is a United States regulatory regime designed to restrict and control the export of defense and military related technologies to safeguard U.S. national security interests. Because some commercial payloads may be sensitive to ITAR restrictions, launching from Hawaii could theoretically be the most south place such a launch could occur without running afoul of ITAR for equatorial orbits.

While not specifically invested in the Alaskan Aerospace proposal, the Hilo, Hawaii-based Pacific International Space Center for Exploration Systems (PISCES) is facilitating conversation between spaceport stakeholders, community members, and government officials. PISCES is a state-funded aerospace agency operating under the Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism (DBEDT). PISCES’ core mission is to develop and grow the aerospace industry in Hawaii through “Applied Research, Workforce Development and Economic Development initiatives” according to their mission statement. PISCES Program Director Rodrigo Romo believes Hawaii could benefit from a small but robust aerospace industry. “I look at what the city of Tucson (Arizona) has done to develop one and see many similarities with Hilo. Both cities have small airports and are located near a large busy airport hub (Hilo – Honolulu / Tucson – Phoenix). Both cities have a university and a community college. Tucson took advantage of this and created a very successful aviation maintenance program through Pima Community College. I believe Hilo could do something similar. This could attract other industry players including small manufacturing, electronics and others.” Romo added, “Obviously Tucson has some advantages over Hilo, for instance the presence of a very large air force base (Davis Monthan) as well as large military contractors (Raytheon) that help create a seed upon which the cluster grew. Recently Vector announced plans of building their manufacturing facility in Tucson creating 200 new jobs building their rockets. Hilo does not have the Raytheon seed, but a launch facility could provide that seed that could attract rocket companies to have assembly and testing facilities with some light manufacturing capabilities.”

On February 6, KSF is hosting an Open House in Hilo for community members to learn from Alaska Aerospace what is planned. This public meeting is part of the process KSF is pursuing with the environmental assessment study currently under way. The Hawaii Legislature appropriated $250,000 in 2018 to support the evaluation of a potential location in East Hawaii for a small lift facility; Hawaii Governor Ige authorized $225,000 to be allocated to this specific initiative with Alaska Aerospace providing additional funds. With the formal Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Environmental Assessment (EA) process underway, Alaska Aerospace is supporting the proposal by providing engineering design and technical support in facility layout. If the environmental process advances successfully, Alaska Aerospace will work with the FAA to obtain a commercial spaceport site operator license for the site. In addition to regulating commercial and private aircraft, the FAA also regulates space travel and rocketry under 14 CFR Part 420. The FAA has already approved 10 such spaceports in the U.S.

Hawaii is no stranger to space science. The Maunakea observatories are located within a 90 minute drive of the proposed spaceport. Located on the summit of Mauna Kea, 13 independent multi-national astronomical research facilities peer into the sky to study different aspects of space. Nearby volcano Mauna Loa is also home to the HI-SEAS lab. Short for Hawai’i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, HI-SEAS is a habitat on an isolated Mars-like site on the Mauna Loa side of the saddle area on the Big Island of Hawaii at approximately 8,200 feet above sea level. Through last year, studies were done with people who would live there for months at a time in a Mars-like environment. The site is being transformed now to simulate moon-based missions planned by the U.S. in the years ahead. NASA has been working on a variety of initiatives in Hawaii due to its unique location, terrain, and volcanic geology for projects ranging from robotics to space materials sciences. Hawaii was also home for famed astronaut Ellison Onizuka; born in Kealakekua, Hawaii, Onizuka became the first Asian American in space and the first person of Japanese ancestry to reach Space. He flew on Space Shuttle Discovery on mission STS-51-C and served as a Mission Specialist for STS-51-L, the ill-fated Space Shuttle Challenger mission that exploded shortly after take-off. Many places are named in honor of Onizuka in Hawaii, including the Big Island’s Kona International Airport which is officially known as the “Ellison Onizuka Kona International Airport.”

While no larger rockets, including manned missions and military craft, will be used at the proposed spaceport, it’s hoped that the presence of such a high-tech facility on Hawaii could inspire young residents on the island to work on future such missions. Romo isn’t predicting the outcome of the Alaska Aerospace proposal, but does believe exploring and perhaps pursuing such opportunities would be beneficial to Hawaii. “I do believe that it is possible to keep an adequate balance between the environment and the community while providing an economic development opportunity for Hawaii’s younger generations.”