The Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station located in Plymouth, Massachusetts is in the process of being decommissioned; a potential plan to discharge 1 million gallons of radioactive waste into Cape Cod Bay as part of that decommissioning project is raising eyebrows and growing concerns about the possibility of radioactive nor’easters in the coming months.

The Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station is located on the western shore of Cape Cod Bay in the Town of Plymouth, Plymouth County, Massachusetts; it is south of the tip of Rocky Point and north of Priscilla Beach. The nearest large cities are Boston, Massachusetts, approximately 38 miles to the northwest, and Providence, Rhode Island, approximately 44 miles to the west.

When operational, the Pilgrim plant was responsible for the generation of 14% of all electricity in Massachusetts.

A decision was made in October 2015 to shut-down the plant; the facility’s owners said “market conditions and increased costs” for future safety updates were cost-prohibitive. Operation of the Pilgrim facility permanently ceased on May 31, 2019 and all fuel was permanently removed from the its reactor vessel on June 9, 2019. By 2027, Holtec International, Pilgrim’s owner, expects all decommissioning work to be completed. However, an independent spent fuel storage installation, or ISFSI, isn’t due to the removed until the end of 2062.

In the meantime, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) which is overseeing the decommissioning, “large volumes of low-level radioactive waste are generated. This low-level radioactive waste requires processing and disposal or disposal without processing, as appropriate.” According to the NRC in filings made in October, the plant operator would transport, by truck or by mixed mode shipments like a combination of truck and rail, low-level radioactive waste from Pilgrim to locations elsewhere in the country certified to store such waste.

However, in a recent meeting of the Nuclear Decommissioning Citizens Advisory Panel in Plymouth, a report by the state Department of Environmental Protection shared there raised the possibility of simply getting rid of radioactive water from the spent fuel pool, the reactor vessel, and other components of the facility by dumping it directly into Cape Cod Bay. The Cape Cod Times reported that “The option had been discussed briefly with state regulatory officials as one possible way to get rid of water”, causing some alarm in the community. However, the a spokesperson tied to the nuclear power plant, Patrick O’Brien, told reporters that the concept of dumping radioactive water into Cape Cod was discussed with the state, but they’ve made no decision on whether or not to proceed.

State Department of Environmental Protection Deputy Regional Director Seth Pickering said many regulatory and approval hurdles must be crossed before any release of radioactive waste into Cape Cod Bay could occur.

“Mass DEP, and the U.S. EPA have made the company aware that any discharge of pollutants regulated under the Clean Water Act, (and) contained within spent fuel cooling water, into the ocean through Cape Cod Bay is not authorized under the NPDES (National Pollution Discharge Elimination System) permit,” Pickering said in the Cape Cod Times article .

However, “radioactivity” isn’t considered under the NPDES as a pollutant; instead, radioactive discharges are regulated by the NRC which could allow the discharge into the bay regardless of the EPA’s position. The NRC has permitted other radioactive discharges into bodies of water elsewhere around the country.

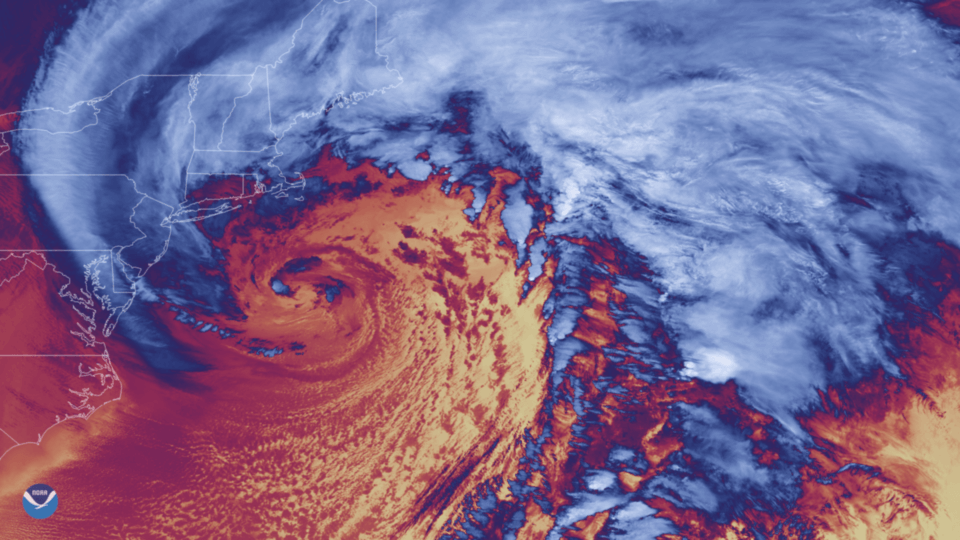

If the million gallons of radioactive water is released into Cape Cod Bay, it would be in an area ripe for nor’easter development that could scatter the radioactive matter across a far area of the northeast. While a storm moving through could help dilute the waste water, it isn’t exactly known what the interaction between a strong coastal storm and a radioactive waste discharge could do.

A Nor’easter is a storm along the East Coast of North America, so called because the winds over the coastal area are typically from the northeast. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), these storms can occur at any time of year but are most frequent and most violent between September and April. Some well known Nor’easters include the notorious Blizzard of 1888, the “Ash Wednesday” storm of March 1962, the New England Blizzard of February 1978, and the March 1993 “Superstorm.” According to NOAA, past Nor’easters have been responsible for billions of dollars in damage, severe economic, transportation and human disruption, and in some cases, disastrous coastal flooding. Damage from the worst storms can exceed a billion dollars.

While nor’easters generally develop in the latitudes between George and New Jersey, +/- 100 miles east or west of the immediate East Coast, they typically reach their maximum intensity when they approach the area near Cape Cod. These nor’easters can produce significant heavy rain or snow, as well as winds of gale force, rough seas, and, occasionally, coastal flooding to the the northeast. While a storm could be at its most intense strength near Cape Cod, their impacts can be felt as far away as Washington D.C., Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and the heavily populated “I-95 Corridor.”

During winter months, the polar jet stream transports cold Arctic air south across the plains of Canada and the United States, then east towards the Atlantic Ocean where warm air from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic tries to move northward. The warm waters of the Gulf Stream located just off-shore the East Coast help keep the coastal waters relatively mild during the winter, which in turn helps warm the cold winter air over the water. This difference in temperature between the warm air over the water and cold Arctic air over the land is the fuel that feeds Nor’easters and makes them that much more powerful during the winter.

Within the next few weeks, workers at the Pilgrim facility should be wrapped-up moving all of the spent fuel rods into casks that are being stored on-site. From there, the removal and disposal of other parts of the facility should continue from December through February. Beyond that, perhaps in about 6-12 months, a decision will be made and executed on what to do with the excess radioactive waste water on the site. If it is released, it could happen in the middle of hurricane season; it could also happen in peak nor’easter season.

If waste water is released into Cape Cod Bay from the plant, it won’t be the first time. Just weeks ago, on November 7, more than 7,000 gallons of waste water from the plant made its way to Cape Cod Bay. Contractors there were doing on-site repairs following October’s strong nor’easter; they inadvertently pumped water from a flooded electrical vault into a storm drain which emptied right into Cape Cod Bay there. While the discharge was not believed to be radioactive and was simply just flood water from the October storm, any discharge, accidental or intentional, radioactive or not, is raising concerns in southeastern New England.